Beauty drives orchids towards extinction

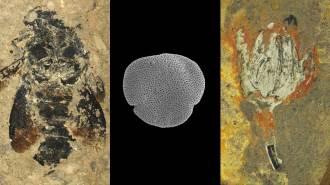

Paphiopedilum callosumis one of several species of slipper orchids now classed as endangered in part because of illegal trade.

Günther Eichhorn/Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0)

- More than 2 years ago

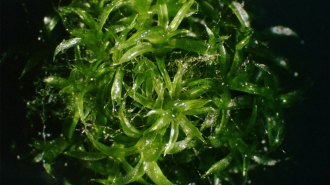

At plant markets in Thailand, exquisite orchids are for sale. Those orchids are unlike the ones you can buy at many U.S. shops; many of them are rare species that were collected from the wild. Selling them is illegal.

This trade is “invisible” because hardly any of it makes it into government statistics that are supposed to document illegal trade in wild flora, Jacob Phelps and Edward Webb of the Center for International Forestry Research in Bogor Borat, Indonesia, note this month in Biological Conservation. The pair conducted a rare in-depth study of trade in wild-collected ornamental plants in Southeast Asia and found 347 orchid species, including many considered threatened, for sale at Thai markets.

Not all orchids are declining, but trade is regulated for every species in the family Orchidaceae, requiring a permit or other approval to sell. That’s because many species are disappearing. And there are some healthy species that look enough like threatened ones that distinguishing between them is difficult. It’s just easier to regulate them all than to risk losing the rare ones. Even stronger controls cover the subgenus Paphiopedilum: All international trade in these orchids is banned.

The reasoning behind these rules was apparent this week. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature released the latest updates to the IUCN Red List— the big database of species that documents threats and assesses conservation statuses. Of the 84 species of Asian slipper orchids, including some Paphiopedilum orchids that were assessed in this round of updates, 99 percent are threatened with extinction.

Habitat fragmentation and destruction, deforestation and illegal logging are contributing to many species’ decline, IUCN notes. But an additional huge concern is that people are collecting these species from the wild for regional and international trade. And though this trade is illegal, no one is enforcing the rules.

Phelps and Webb documented this untrammeled trade in Thailand. They visited plant markets across the country in 2011 and 2012, surveying the species for sale and speaking with vendors. The researchers found orchids for sale from across the region, mostly from neighboring countries. Such international trade was illegal, but it occurred in the open. And it didn’t show up in any official statistics of illegal trade.

“The huge discrepancy between observed and reported trade is alarming, and demonstrates the need for strengthened botanical conservation efforts that include improved trade monitoring,” the researchers write.

Monitoring the markets wouldn’t take much effort, they say. Their surveys took a couple of people only a day or two per site. And it takes only a little training to distinguish a wild-grown plant from a cultivated one. “The open and prevalent nature of trade in protected plant species means that monitoring is viable, given increased commitment and reasonable levels of investment into capacity building and human resources,” they write.

The new IUCN listing shows why such a commitment is necessary. And local people in Southeast Asia have already told scientists that wild orchids are quickly becoming much harder to find. If such trade is allowed to continue, the only orchids left in the world could be the common ones you find in local shop. And the Earth would be a far less beautiful place.