Trapping Compact Fluorescents’ Toxic Gas

Normal 0 false false false MicrosoftInternetExplorer4

Because of the mercury vapor in all fluorescent lights, most municipalities have designated such bulbs and tubes as hazardous wastes that should be kept out of the trash. Yet these lights can be good for the environment in more ways than one (as I noted yesterday) — even as they threaten to pollute our homes if they break (see my last blog). For those who want greener lighting — and to keep mercury out of the environment — here’s some reassuring news.

Free recycling of compact fluorescent bulbs — the palm-size curly lights that fit into conventional lamps and fixtures — just became widely available. And should one of these CFLs break, there may soon be a way to render its mercury harmless.

To find a fluorescent-light recycler near you, key your zip code into the Earth911 website. If you live in a large metro area, chances are the majority of listings will be for Home Depots.

This chain announced in late June that it was launching a CFL take-back program in all its U.S. stores. “With more than 75 percent of households located within 10 miles of a Home Depot store, this program is . . . a convenient way to recycle CFLs,” boasts Ron Jarvis, a senior vice president of the Atlanta-based home-improvement retailer. Alas, its stores won’t take back other fluorescent lights, such as those long tubes used to illuminate most basement work benches.

Home Depot is not restricting its take-backs to the CFLs it sold. I’m guessing the company views this as one way to invite customers in for impulse buys — perhaps a new house plant or set of replacement drill bits. Then again, when it comes to light bulbs, Home Depot is the biggest kid on the block. Last year it sold 75 million CFLs.

Jean Niemi, a spokesperson for the chain, explains that when someone enters a Home Depot, they’ll find a designated area where they can drop off batteries, cell phones, or CFLs for recycling. For the fluorescents, “you just put them in a plastic bag that’s provided for them, and throw them in a big bin.”

I’m hoping she didn’t mean that literally, because these bulbs aren’t robust enough to take much physical abuse. Moreover, as chemical engineer Robert Hurt and his students at BrownUniversity have found, conventional plastic bags won’t keep mercury from escaping — in this case into the store.

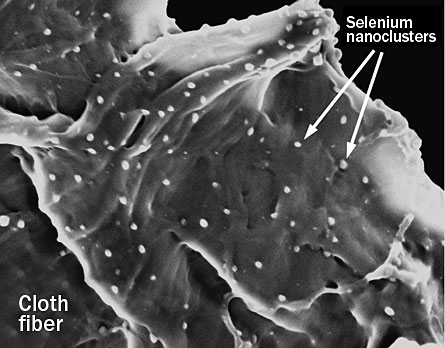

But the Brown engineers might just have a solution for preventing any leakage of mercury into Home Depot’s air from carelessly tossed CFLs. It’s a novel recipe for nanomaterials that sop up gaseous mercury and convert it into an inert compound. Hurt’s team reported its finding in the Aug. 1 Environmental Science & Technology.

Of the commercial materials created to collect spilled mercury, none had been designed to cope with CFL breaks. So the Brown engineers tested 28 different chemicals, some of them totally novel. The best performer: amorphous nanoselenium particles no more than 60 billionths of a meter in diameter.

In lab tests, these orange nanoparticles trapped and neutralized 99.9 percent of the mercury vapor they encountered. Indeed, they proved so potent that just a few milligrams rendered inert a milligram of mercury — an amount comparable to what a broken CFL would release. Hurt’s team found that for some other contenders, such as powdered sulfur or zinc, quantities in excess of 10 kilograms (clearly not a commercial option) would be needed to neutralize a milligram of mercury.

In the nine months since the Brown researchers submitted their paper to ES&T, they’ve been breaking bulbs and testing how well prototype treatment strategies perform — such as covering broken bulbs or spills of CFL debris with fabrics impregnated with their novel nanoparticles.

And the results? Laying one such fabric atop contaminated carpeting trapped the mercury it had been emitting. Leaving it on the spill site for a week, Hurt says, should neutralize virtually all of the mercury while keeping the toxic vapors from entering the air and moving to other sites.

Once the reactive end product develops, this mercury selenide “remains stable, under normal conditions. For instance, it should be stable in landfills,” Hurt says.

But CFLs aren’t the sole raison d’être for Brown’s novel nanoselenium. These particles could be plated onto the inside of boxes that carry fluorescent tubes to stores or recycling centers. Heavily treated cloths might even be used in the final stages of wiping up mercury spills from old thermometers or other equipment, Hurt notes.

Several companies have expressed keen interest in the technology, Hurt says. So he anticipates nanoselenium treatment kits might find their way onto store shelves within a year or two.