How medicine is ‘barely managing’ the isotope crisis

For the past three months, health-care providers have been scrambling to maintain quality patient care as world supplies of a key medical-imaging agent — technetium-99m — have diminished to record low levels. Nuclear medicine relies on this one isotope for roughly 85 percent of diagnostic imaging, some 300,000 U.S. procedures in a typical week.

Over the past few weeks, what had been a months-long, nearly-40-percent shortfall in supplies of Tc-99m’s feedstock — molybdenum-99 — roughly doubled, to production levels that now are only about 30 percent of normal.

Overall, most patients have not felt the Tc-99m crunch. But that’s only because of major global cooperation between feedstock producers, nuclear pharmaceutical suppliers, hospital staff and physicians. As Michael Graham, a nuclear medicine physician and president of the Society of Nuclear Medicine, told me last week: “Right now, we’re managing, but just barely.”

In some cases, patient care is undoubtedly being compromised, observes University of New Mexico professor Jeffrey Norenberg, executive director of the National Association of Nuclear Pharmacies. For instance, there are tests that can be substituted for those that rely on Tc-99m. However, most are either not as good — or not covered by insurers.

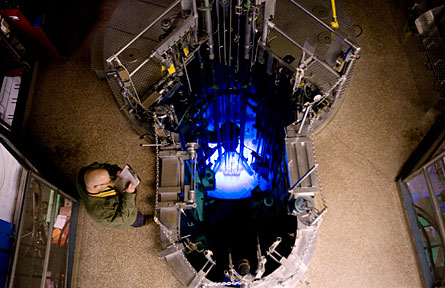

The isotope crisis was kick-started in mid-May with the shutdown of the biggest of the five reactors responsible for making 95 percent of molybdenum-99. Safety crews had spotted a small reactor-vessel leak. When the corrosion that was responsible in this 52-year-old Canadian reactor turned out to be more pervasive than originally thought, the reactor was prescribed a full-scale check up. Its diagnosis: extensive corrosive pitting and up to nine spots on the reactor vessel that will need repairs.

Last week, Atomic Energy of Canada Limited said its moly-99-production reactor could remain shut down until March of next year.

In mid-July, the second of the primary moly-99 reactors — this one in Petten, the Netherlands — shut down for scheduled maintenance. It should remain down for another week or two. But it’s due to return to service for only six months. Then it will shut down again for up to six months — this time to make repairs on problems triggered by corrosion in the 47-year-old facility. The remaining major moly-99 producers in South Africa, Belgium and France, all older than the Petten facility, have tried to increase their moly-99 production some. But they’re limited in how much more they can make.

So managing the current moly-99 crisis hasn’t been easy. Indeed, even before the Petten shutdown, it was impacting medical centers large and small, especially across North America.

Like at Advocate Good Samaritan, a 330-bed hospital in Downers Grove, just west of Chicago. Ordinarily, it performs some 135 procedures a week that rely on Tc-99m, according to Dina Loughlin, director of diagnostic imaging services at the hospital. Now, someone who is scheduled to get a nuclear stress test of the heart on Tuesday may have their procedure postponed until Friday. Or, she notes, “we look at what else can be done in substitution.”

Indeed, there are substitute procedures for many Tc-99m imaging tests. Take those cardiac stress tests, which account for almost half of the isotope’s use today. Long before a technetium-based procedure came onto the scene to measure blood flow in the heart, thallium-201 was routinely used for this purpose. Physicians can still go back to that radioisotope. But the thallium test costs more, Graham says, and delivers roughly twice the radiation dose to the patient.

Norenberg agrees that “much of the unmet [Tc-99m] needs in cardiac imaging could be converted to thallium. But at a cost: There would be compromises in the diagnostic ability because the technetium is superior in terms of accuracy, sensitivity and specificity.” And he says there’s also some question about whether there would even be enough thallium available “if we attempted a 100 conversion to thallium for cardiac imaging.”

For bone scans that probe signs of cancer, there is an imaging procedure that appears to be at least as efficacious as ones that rely on Tc-99m. Moreover, it’s probably no more expensive, notes Graham. However, at least right now, Medicare won’t pay for this alternative. And when Medicare won’t, neither will most insurance companies, he says. Uncle Sam has promised to investigate whether its policy on excluding coverage of the alternative bone scans should be changed, but expects no decision for at least six months (see Feds won’t cover PET scans during isotope crisis).

So far, notes Loughlin of Advocate Good Samaritan, at her hospital “there’s been no needs to ration [Tc-99m], because we are triaging effectively. All the ‘must haves’ are getting the tests they need” on time. Those who don’t need to be urgently imaged may have to wait a few days or so, she says — or settle for some alternate procedure.

Some hospitals and health centers have explored another coping strategy: stretching limited isotope supplies by working longer hours. Explains Norenberg, most imaging centers work standard business hours, perhaps 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. But half of any technetium atoms will decay to something that’s not medically useful every six hours. So all of the isotope that becomes available in off-hours is wasted. Unless imaging centers operate 24/7.

They don’t do this, of course. But the longer they operate, the more procedures that they can squeeze out of the limited Tc-99m feedstock.

So, this is what Graham means when he says, “We’re managing, but just barely.” And most experts in this area worry that while the intensity of the crisis may relent at times, it is unlikely to really be over for at least another year.

NEXT: Feds won’t cover PET scans during isotope crisis