Gloves may head off ‘garden’ variety pneumonia

Doctors have begun linking garden compost to an unusual source of Legionnaire’s disease

Compost feels so good, sifting through a gardener’s fingers. Unfortunately, data are showing that this soil amendment can host a germ responsible for Legionnaire’s disease, a potentially serious form of pneumonia.

The risk of picking up a Legionella infection from compost is rare, points out Simon Patten, a physician specializing in internal medicine at Royal Alexandria Hospital in Paisley, Scotland. Just nine instances have turned up in the United Kingdom within the past 26 years.

Scotland hosted four, however, within just the past three years — including one case that Patten’s team treated this spring.

A 67-year-old man came to the hospital in March, feeling feverish, confused, short of breath, lethargic — and just generally punk. His abdomen was tender and a chest X-ray showed his left lung was full of gunk (the diagnosis was pneumonia). As time progressed, the man got worse and was admitted to an intensive care ward.

While taking a medical history, the doctors learned that this previously robust individual was a gardener. His left index finger “looked dirty,” Patten recalls, “which is what drew us to ask how he’d gotten a cut on that finger.”

Two days before the fever set in, the man had had been out planting, using compost. At some point, he cut his finger with a trowel or some other garden implement. Even a week later, at the hospital, the finger didn’t really look inflamed, Patten says. But it appears this was the entry route for the germs.

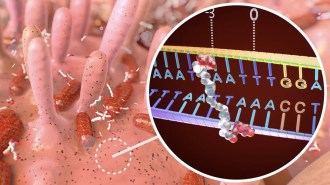

A 24-hour urine test will pick up the most common strain of disease-causing Legionnella. This man’s urine came back clean — and antibiotic therapy wasn’t making him any better. So the medical team cultured the man’s blood for a rarer strain of the bug. And five days later results came back confirming the presence of L. longbeachae, a bacterium sometimes hosted by compost. It’s also a form of the bacteria that’s resistant to the first-line battery of antibiotics.

Patten and his colleagues switched the man’s antibiotics and within a month the gardener was right as rain. A synopsis of his case appears in the Sept. 4 Lancet.

But even before his infection, the bug that felled him had been developing a bit of notoriety. On Feb. 25, Eurosurveillance issued a rapid communication linking a trio of Legionnaires’ disease cases to potting compost in Scotland. “The exact method of transmission is still not fully understood,” the authors noted, but these new cases “call for an introduction of compost labeling.”

And indeed, less than a month later, the Royal Horticultural Society issued a list of recommendations to limit potential exposure to any Legionnella that might be in lurking in compost.

A niggling question is why compost has emerged as a risk factor for L. longbeachea. Dirt can host the germ, but usually in low concentrations, Patten says. He suspects that something about the nature of compost — its moisture levels, nutrient richness or something else — might just prove especially conducive to fostering growth of this microbe.

In Europe and the United States, L. longbeachea is rare, accounting for fewer than 5 percent of Legionnaires’ diagnoses. Not so in Australasia. Indeed, a new paper in the September Clinical Microbiology and Infection finds evidence that in New Zealand, L. longbeachea is at least as common as any other Legionella species.

Matthew Amodeo of Canterbury Health Laboratories in Christchurch, New Zealand, and his colleagues analyzed blood from 50 cases of Legionnaires’ disease treated at Christchurch Hospital between 1998 and 2008. Of these, 48 percent of cases involved L. longbeachea and 40 percent stemmed from infection with L. pneumophilia (the germ responsible for some 90 percent of Legionnaires’ disease in the United States).

There had been little difference in the health of the New Zealanders prior to their contracting a Legionella infection. For instance, those with L. longbeachea were not more likely to be immunocompromised (as they typically have been in the United States).

What the new data point to, Amodeo’s team says, is that L. longbeachea isn’t rare everywhere. And identifying it may require adding blood tests to the quick urine assays typically administered in the Northern Hemisphere.

I guess it also means we gardeners should become fairly religious about donning gloves before we root around in compost.