U.S. backs $100-billion-a-year plan for climate adaptation

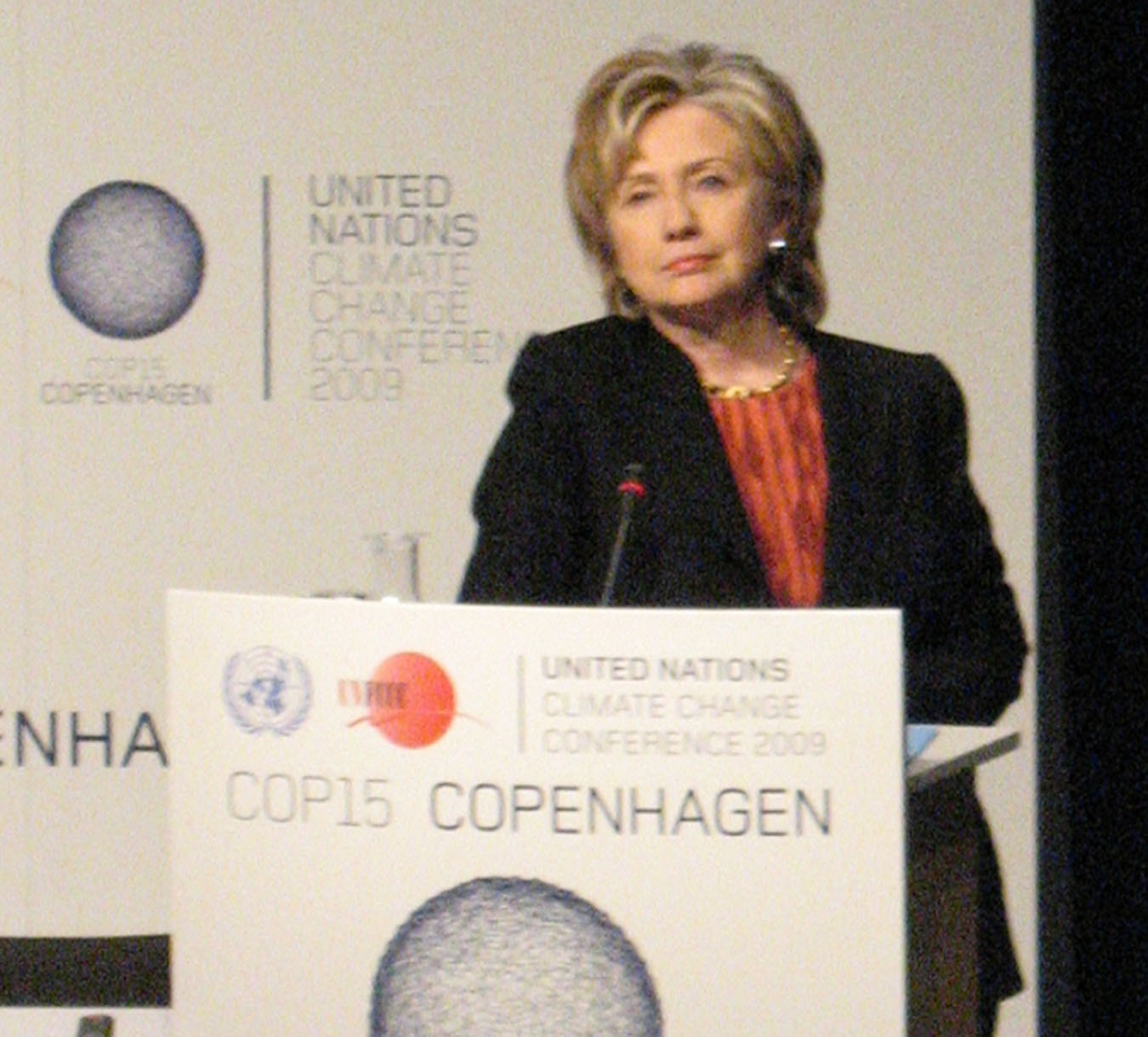

U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton arrived at the climate talks December 17

COPENHAGEN — “The United States is prepared to work with other countries toward a goal of jointly mobilizing $100 billion a year by 2020 to address the climate change needs of developing countries,” U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton announced at a press conference this morning, a few hours after she arrived at the United Nations climate change meeting.

Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel, speaking a few hours later at the climate change meeting, said she “is glad to see today that the United States is willing to do so,” since Germany and the European Union have already acknowledged their willingness to shoulder their fair share of a “100 billion” a year climate adaptation and mitigation fund by 2020.

Less impressed was Jo Leinen, chairman of the European Parliament‘s delegation to the climate-change meeting. He noted that the European Union’s proposal was for investing 100 billion euros a year into a fund for meeting the climate needs of developing countries — a value 44 percent higher than the dollar value that Clinton mentioned.

In any case, Clinton’s announcement indicates that “the United States has joined other rich economies to signal a greater seriousness about helping developing countries and building a more solid international deal,” according to Jennifer Morgan, climate-program director at World Resources Institute in Washington, D.C. However, Morgan added, more details are needed, “particularly whether this money will be additional to current funding. But this is a solid first step.”

Clinton ducked the issue of how much money the United States would contribute. She also said that U.S. commitment to such long-term financing of climate change mitigation and adaptation efforts in the hardest hit developing countries would be conditional upon other nations — including, but not only, China — agreeing to “transparency” in the verification of their cuts in greenhouse gas emissions.

Indeed, transparency has been a loaded word, here at the climate change meeting. It has come up daily in connection with discussions of cuts in emissions of greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide. Achieving those cuts is the prime directive of this meeting. And within the context of the global negotiations, transparency is often referred to as MRV — for the mandatory “measuring, reporting and verifying” of emissions.

Industrial countries are the only ones currently required to cut their emissions, although developing countries with substantial emissions (think China and India) are being strongly encouraged to voluntarily reduce at least their “carbon intensity,” which is the amount of greenhouse gases emitted per unit of industrial activity (as measured by gross domestic product). And many major countries in this second-tier group (nations not yet required to cut emissions) have pledged to indeed reduce their carbon intensity. Keep in mind: Cutting carbon intensity won’t necessarily reduce a country’s emissions. It would just slow how quickly those emissions grow.

The MRV rubric of the ongoing negotiations would require that emitters must let outside auditors ensure they’re living up to agreed-upon commitments.

But recent news reports have suggested China may be a bit squeamish about signing on to such MRV’ing. When asked about this today, Clinton said: “It would be hard to imagine, speaking for the United States, that there could be the level of financial commitment that I’ve just announced in the absence of transparency” from China. Without a commitment to pursue transparency, “that’s sort of a deal breaker for us,” she said.

Indeed, signing on to translucency rather than transparency is hard to countenance, she said, because “There have been occasions in this past year when all of the major economies [including China] have committed to transparency.”

Such political posturing over emissions reductions and financing issues have been common at this meeting. Negotiators from some blocks of developing countries have at times walked out of the climate talks to protest the apparent lack of interest by industrial nations in providing assurances that the needs of poorer and largely nonindustrialized countries will be met. Industrial powers have proclaimed their willingness to set up funding programs to aid developing countries ravaged by climate change — but none of the potential donors has pledged the amount of money to which developing countries feel they’re entitled. For instance, one block of African countries has been arguing here that it needs perhaps $500 billion in the near term (the next three to five years) to compensate them for the climate change problems they’re experiencing due to industrial countries’ emissions.

When it comes to transparency, what’s the big deal? Why would a nation be reluctant to have its emissions cuts verified? “It runs into sovereignty issues,” explains Elliot Diringer of the Pew Center on Global Climate Change in Arlington, Va. MRV requirements raise questions about the degree to which countries “are willing to subject their actions to international scrutiny and the terms of that scrutiny.”

Any serious movement toward negotiating a new climate treaty will “need verifiable commitments,” Diringer said yesterday at the meeting. “But I don’t know if we’ll be able to [define adequate] verification until we’re ready to close a final deal.” Indeed, he maintained, “Because everything here [at the Copenhagen meeting] is provisional, we may not be seeing countries’ best offers on that issue. So I think that as far as we get on MRV here, it won’t be the final MRV. That will have to come later.”

How much later? Well, there’s a pretty strong suspicion that negotiators will leave Copenhagen this weekend without having agreed upon the final language for a new and “binding” treaty. In other words, post-meeting negotiations will likely continue — to iron out the precise language of how to cut emissions, protect climate-moderating resources (such as forests) and provide funds to help developing nations adapt to climate alterations — over the next six to 12 months. In time for December 2010’s UN climate change conference in Mexico City.

See also: Climate deal reach, importance debated