Scientists offer compelling images of Gulf War illness

Depicting brain damage, scans distinguish between a trio of syndromes, researchers say

SALT LAKE CITY Nearly two decades after vets began returning from the Middle East complaining of Gulf War Syndrome, the federal government has yet to formally accept that their vague jumble of symptoms constitutes a legitimate illness. Here, at the Society of Toxicology annual meeting, yesterday, researchers rolled out a host of brain images – various types of magnetic-resonance scans and brain-wave measurements – that they say graphically and unambiguously depict Gulf War Syndrome.

Or syndromes. Because Robert Haley of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas and the research team he heads have identified three discrete subtypes. Each is characterized by a different suite of symptoms. And the new imaging linked each illness with a distinct – and different – series of abnormalities in the brain.

Men with the same symptoms exhibited similar brain changes, features starkly different from healthy vets their age who had served in the same battalions. (That said, a few vets’ symptoms seemed to encompass more than one syndrome. And in such instances, imaging confirmed their brains showed impairments that extended beyond those associated with a single syndrome.)

Since the early 1990s, some 175,000 U.S. troops have returned from service in the first Gulf War reporting a host of vague complaints, notes Richard Briggs, a physical chemist at UT Southwestern involved in the new imaging. Their symptoms ranged from mental confusion, difficulty concentrating, attacks of sudden vertigo and intense uncontrollable mood swings to extreme fatigue and sometimes numbness – or the opposite, constant body pain.

With funding from the Departments of Defense and Veterans Affairs, Haley has assembled a team of roughly 140 researchers. Many work with patients. Others are developing new animal, biochemical and genetic studies to identify the biological perturbations underlying Gulf War Illness. But the vast majority – some two-thirds of these scientists – are now involved in brain imaging.

As a result of these studies, Briggs says, “In the last two years we have learned more about Gulf War Illness than we did in the previous 15.”

What’s emerged is evidence to suggest “that there are three major syndromes responsible for Gulf War Illness,” he says. They appear loosely linked to at least three different types of agents to which many troops were exposed: sarin nerve gas, a nerve gas antidote (pyridostigmine bromide) that presented its own risks and military-grade pesticides to prevent illness from sand flies and other noxious pests. But Briggs acknowledges that no one knows for sure which combination of agents or environmental conditions might have conspired to trigger Gulf War illness.

What is clear, he says, is that “our data now clearly show, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that there are brain abnormalities – physiological differences – between ill veterans and normal ones.” And from the new scans, “we can tell the ill veterans from the well veterans. And we can distinguish syndromes one, two and three from each other.”

The new neuroimaging on a subset of 57 Gulf War vets was completed eight months ago. Yesterday’s presentations represent an unveiling of the complex statistical analyses of data gleaned from those functional MRI scans (or fMRIs), brain-wave recordings, and other magnetic resonance tools.

Some testing employed old-style technologies. For instance, about a dozen years ago, Haley’s team performed magnetic resonance spectroscopy, also known as MRS, to study the chemical composition of various regions in the brains of Gulf War vets. And these tests uncovered the first solid indicators that there were physiological abnormalities in men complaining of Gulf War Illness. Such as a perturbation in the ratio of two chemicals active in the brain’s basal ganglia: n-acetyl aspartate (or NAA) and creatine.

Don’t know what that means? I didn’t either. So Briggs explained.

“The basal ganglia is sort of the switching system of the brain. It’s where a lot of communication between the left and right hemispheres occurs.” Because it crosses the midbrain region, he says, “it’s heavily involved in a lot of these decisionmaking and attention/inhibition networks” – processing centers that, if messed up, could explain many symptoms reported by sick vets.

NAA is a biomarker of healthy nerve cells. So any decrease is a bad sign. The concentration of creatine, which comprises the fuel for brain activities, tends to remain constant, Briggs says, so “it’s often used as an internal standard” against which to compare things like NAA.

The Gulf War syndromes are each associated with a roughly 10 percent lower than normal NAA-to-creatine ratio in the left and right basal ganglia, Briggs says – “an indicator of either sick or dead neurons.”

After Haley’s team initially published evidence in the late ‘90s of the diminished NAA-to-creatine ratio in sick vets, two other labs confirmed this characteristic MRS feature in sick Gulf War veterans, Briggs notes. More recently, when one of those labs failed to reconfirm those changes during a followup study, the UT Southwestern team began to wonder whether it had erred the first time it had conducted the pioneering tests. Or whether the sick vets had simply gotten well over the past 10 years.

“Our new follow-up [MRS] tests now show our initial findings were right,” Haley says – “and that the soldiers haven’t gotten better with time.”

Many of scans that his team unveiled here at SOT rely on a technology – fMRI – that was not available in the late ‘90s. So it provides new evidence of what sets sick vets apart.

This technology allows researchers to identify which areas are active as the brain works. Haley’s multi-center team designed a series of fMRI tests that required subjects to look at threatening pictures of a battlefield, or imagine the theme behind two words to come up with a third (“desert” and “humps” might be the clues given to suggest “camel”), or to learn words and recall faces.

In healthy veterans, appropriate parts of the brain lit up as they thought, reasoned, viewed – even experienced extremes of temperature. But in men suffering from Gulf War Illness, Haley says, “a different part would often light up as their brain attempted to work around its damage.”

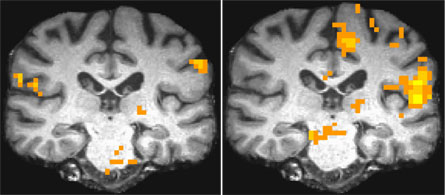

Affected areas of the brain in each test varied. The thalamus, for example, is involved in attention and inhibition, Briggs explains. “It is activated differently in syndrome two versus controls,” he notes. Not surprisingly, people with that particular syndrome have problems with those traits. The researchers also correlated what combinations of areas in the brain respond in concert during particular tasks. And sometimes, the collection of brain locales that lit up in sick vets differed markedly from those in healthy vets (see images above).

The background volume of blood flowing through the brain also varied substantially in sick vets, Haley notes, “which suggests decreased [brain] function.” But even more importantly, blood flow varied in unpredictable ways when the sick Gulf War veterans were administered a drug meant to stimulate parts of the brain susceptible to chemical damage, such as nerve-gas-type agents.

In healthy vets and those suffering from syndrome one, blood flow to affected regions of the brain diminished, although not comparably; the drop in syndrome-one vets was about five times that in the healthy men. But among individuals suffering from Gulf War syndromes two and three, blood flow inappropriately spiked after administration of the drug.

Other tests probed for faults in the integrity of the circuitry connecting deep gray matter – where the brain performs unconscious calculations and processing – with the layer of white matter that performs conscious reasoning. In vets with syndrome two, the most seriously ill of the groups, a special form of scans showed signs that the insulating sheath covering the “wires” connecting the gray and white-matter regions was seriously impaired.

Concludes Briggs: “This tells us very clearly that in the syndrome two’s – unlike either of the other syndromes, or the controls – their wiring is flawed.”

The panoply of quantitative changes being revealed by brain imaging “is demystifying Gulf War Syndrome,” says Haley. Indeed, before long, he predicts, “we’re going to come up with tests whereby doctors can diagnose affected vets.” And one day, he hopes, the information emerging from these images may actually point toward treatments.