Serotonin lies at the intersection of pain and itch

When you've got an itch, you have to scratch. But often scratching just makes the itch worse. The reason? Serotonin.

magdasmith/iStockPhoto

- More than 2 years ago

I itch. Constantly. Evenings tend to be the worst. But then, mornings are pretty bad too. I have atopic dermatitis, commonly known as eczema. The symptoms include very dry, scaly skin in the creases of the elbows, the backs of the knees, and on the hands and face, accompanied by terrible itching. Even with medication and plenty of moisturizer, the itching is intense, especially with winter on the way. I know I’m not supposed to scratch, but I do. The scratching causes pain, but the relief from the itch is so great I get weak in the knees. And, in a few seconds, the itch returns, often worse than before.

I’ve often wondered why scratching doesn’t ever work. Now, a study shows that the answer lies in an interesting quirk of our physiology. Where pain and itching intersect, there is a chemical messenger: serotonin.

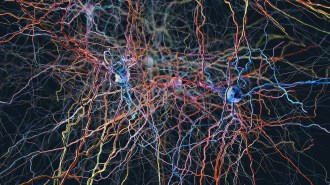

Itching and pain have many commonalities. They share a common pathway in the spinal cord, the spinothalamic tract. Patients who are insensitive to pain are also insensitive to itch. Pain and itch even activate similar sensory areas in the brain.

But there are some crucial differences between pain and itch. The two sensations produce very different responses. When we feel light touch, we itch. The response is the scratch, to get the bug or other irritant off of the skin. But pain, whether from a cut, a hot stove or any other danger, elicits a very different behavior. Then, the urge is to pull the injured body part away, and to keep it away. Drugs such as opiates may suppress pain, but they exacerbate itch. And scratching, which can induce pain, relieves itch. At least for a moment.

Zong-Qiu Zhao and colleagues at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis were interested in the role of the chemical messenger serotonin in itch and pain. Serotonin often appears in the news related to psychiatric conditions and mood. But chemical messengers, or neurotransmitters, have different effects depending on where they are released. They also have varying effects if they act on different receptors — proteins in cell membranes that bind neurotransmitters and control cell responses.

Serotonin itself is a busy chemical. There are more than a dozen receptors for it, each performing different and sometimes opposing tasks, depending on their placement. In the brain, serotonin plays roles in mood, circadian rhythms and hallucinations. In the gut, serotonin helps to control whether or not you end up with diarrhea. And in the skin, serotonin can play a role inhibiting pain — and exacerbating itch.

Zhao and colleagues used mice to study serotonin’s role in the skin. Of course scientists can’t ask whether a mouse is itching. But they can watch to see how much it scratches. Injections of irritants that cause itching on the back of a mouse’s neck reliably produce vigorous mousey scratching.

In a study published October 30 in Neuron, the scientists show that mice genetically altered so they don’t produce serotonin didn’t scratch as much as normal mice when exposed to irritants. But when the researchers gave the low-serotonin mice injections of a serotonin precursor, the mice began scratching away at their newly felt itches.

Further experiments showed that descending serotonin neurons, coming from the brain and spinal cord, contact a type of neuron that expresses gastrin-dependent peptide receptors. To Zhou-Feng Chen, a neuroscientist at Washington University and a study coauthor, these neurons had long been a puzzle. “We were looking for genes that might be associated with pain sensation in the spinal cord,” he says. “We came across a receptor called the gastrin-dependent peptide receptor, and we saw they were in the right place in the spinal cord for pain.” Chen’s lab started eagerly studying the role of gastrin-dependent peptide receptors in pain. But, Chen says, they were in for a surprise. “The receptor has nothing to do with pain,” he says. Instead, Chen and his lab found that the receptors were activated when mice scratched.

If serotonin-releasing brain cells connect to cells that express gastrin-dependent peptide receptors, serotonin might be able to activate those receptors and result in itch, the researchers reasoned. Zhao, Chen and colleagues found that these gastrin-dependent peptide receptor-expressing cells also express a type of serotonin receptor known as the 1A receptor. When they activated these receptors with specific drugs, the mice scratched away.

A closer look showed that the two receptor proteins, 1A and the gastrin-dependent peptide receptor, are located very close together on the cell membrane. So close, Chen says, that they may be interacting. This interaction means that when serotonin, released in response to pain, hits the 1A receptor, the gastrin-dependent peptide receptor is affected too. The net result is that when the mouse scratches an itch, the pain causes the release of serotonin. The serotonin causes pain relief, but then activates the 1A receptors, and then it’s time to itch.

“Serotonin has been known to be an itch induced when injected into humans,” says Earl Carstens, a neurobiologist at the University of California, Davis. But he says that in general, “very little is known about the central modulation of itch.” He says this new paper is “excellent” and helps to address some of the complicated questions underlying the interaction of pain and itch.

There are already drugs and chemicals that target 1A receptors. It is possible that some of these might prove effective for those, like me, who suffer from chronic itch. Unfortunately, Chen notes that such developments probably have “a long way to go.” But in the meantime, he says, “we provide an explanation for an interesting thing that everyone experiences. Everyone itches, and when they scratch, they itch more! Now we know why.”