Bingeing rats show the power of food habits

A new study suggests that repeated binges on sugar and fat could tilt the neural balance from taking a few modest bites of a tasty dessert toward devouring an entire sundae — and then some.

rojoimages/iStockPhoto

- More than 2 years ago

Many of us have experienced that depressing sight: The bottom of the ice cream pint. You get to the end of your favorite movie and suddenly realize the ice cream is gone — and you’re far too full for comfort. We’re left wondering why we did it. But when it comes to forgetting ourselves and bingeing on the pint, the power of habit can be strong.

It could be that our previous eating experiences make us helpless to our habits. A new study in rats, published April 2 in the Journal of Neuroscience, shows that long-term exposure to bursts of sweet, fatty foods produces animals that appear to seek food not out of hunger, but out of habit. And neural changes associated with habit formation accompany the behavioral changes. The results suggest that repeated binges on sugar and fat could tilt the neural balance from taking a few scoops of Cherry Garcia toward mindlessly reaching the bottom of the bowl. But while the results show us the power of habit, bad habits don’t necessarily make us food addicts.

Teri Furlong and her colleagues at the University of Sydney in Australia were interested in how animals control behaviors. Some behaviors are goal-directed, while others are more efficiently taken care of with habits. Furlong describes habits as “behaviors where we are not thinking about the consequences as we do them.” Many habits can be useful things to develop — eating breakfast daily or brushing your teeth, for example. But other habits can become maladaptive, such as drug abuse — or binge eating.

Furlong and her group had been examining habits and goal-directed behaviors in the context of drug abuse, and they wanted to see whether their model of behavioral control extended to overeating. So they gave rats normal chow or chow plus delicious sweetened condensed milk. Half of the milk group got milk all day every day, as much as they wanted. The other half only got their sweet milk fix for two hours each day.

After five weeks of this treatment, the scientists trained all the rats to press levers — one lever delivered sweet sucrose pellets, and the other tasty grain. For the test, the animals feasted on either delicious grain or sweet sucrose, and were then given access to a lever. In one scenario, rats saw the lever for the food they hadn’t had access to before. So if they had filled up on grain, they got a sucrose lever. In this case, all the rats still hammered away on their levers. After all, if you’ve just had a huge steak dinner, you’re not going to ask for more steak, but you might still ask to see the dessert menu.

In another scenario, the rats got access to a lever that served them what they had just filled up on. If they had stuffed themselves on grain, they got the lever for more grain. If sucrose, more sucrose. In this condition, control rats and rats given constant access to the milk stopped pressing they lever. They were full, thanks, and didn’t want more of what they’d just been pigging out on. But rats that had five weeks with intermittent, binge-like access to the sweetened milk responded differently. They kept pressing for grain, even though they were full of grain, and kept pressing for sugar, even though their sweet tooth should have been satisfied. The rats weren’t pushing the lever because they could use some more grain. Instead, they were pressing the lever out of habit.

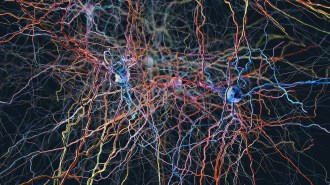

This lever-pressing routine was associated with increased activity in the dorsolateral striatum, an area of the brain associated with habitual behaviors. The scientists hypothesized that the increased activity in this area could be the cause of the repetitive responding. Squirting drugs into the dorsolateral striatum to block glutamate, a chemical messenger that is associated with increased brain activity, reversed the behavior of the rats, making them stop for a moment and realize that actually, they were full of grain, thanks. Rats also stopped their lever-pressing habit when researchers blocked the animals’ receptors for dopamine, a chemical messenger associated with feelings of reward in response to food, sex or drugs.

Furlong says the results are comparable to other studies with drugs of abuse like cocaine, producing “the same loss of behavioral control.” That loss is a shift away from making a goal directed decision (do I really need more grain?) to habit (just push that lever). Laura Corbit, a behavioral neuroscientist at the University of Sydney and an author on the study, says that the study shows that sweet and fat are powerful rewards that “have a fairly broad effect on decision making.” The animals weren’t just responding for the milk they had been bingeing on, the habit carried over to other palatable foods.

Corbit says that studies like this might help to determine how to intervene in these habit-based behaviors. “Information-based interventions are unlikely to work if a person’s behavior is relying on habit,” she says. “Simply telling someone not to eat is not going to work, we need to understand what triggers the habit and find more suitable cognitive interventions.”

Repeated bingeing on delicious foods appears to shift rats toward habits where they aren’t thinking about what they are doing. But does this mean we can talk about this habit as food addiction? Sietse Jonkman, a behavioral neuroscientist at Mt. Sinai School of Medicine in New York City, says that thinking about food bingeing in terms of habit could be useful for both drug addiction and overeating. “There is strong overlap in some of the behaviors we see after drug and palatable food consumption,” he says. “We know that drugs of abuse activate reward circuits that are built for food rewards, so you could see that they could be similar, and there are some aspects of obesity which seem comparable to drug addiction.”

But Trevor Robbins, a behavioral neuroscientist at the University of Cambridge in England, says that while severe binge eating might be considered an addiction-like behavior, “you can’t consider food as an addiction in general. I think the better comparison is with binge eating and binge drug taking.” The tasty milk binges the rats experienced, he explains, are like binge drug sprees in that they are “an intensely motivational scenario that leads to accelerated habit learning.”

Scientists still need to understand what mechanisms underlie the shift from a few evenings with pints of ice cream to a mindless habit of eating. And we still don’t know how much bingeing is “like” drug addiction. After all, we can live without cocaine or alcohol, but life without food is not life at all. While binge eating and binge drug use might be comparable in some ways, they also have many differences in terms of access and social consequences. In the end, that night with the ice cream pint may be just a bad night. Just don’t make a habit of it.

Follow me on Twitter: @scicurious