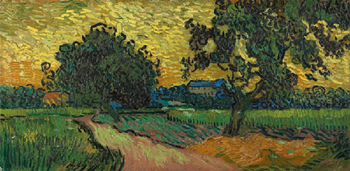

Here’s how a child sees a Van Gogh painting

Kids are initially drawn to bold, bright areas of paintings, but their gazes can change after learning more about the work, a study finds.

byebyetokyo/istockphoto

- More than 2 years ago

One of the best things about having young children is that they give you a new way to see the world — a total cliché, yes, but true. Rainbows in water fountains are mesmerizing. Roly-poly bugs are worth stopping for. Bright blouses on strangers are remarked on, loudly. It’s occasionally embarrassing but always fun to see how this gorgeous world captivates children.

An inventive new study attempted to get inside the minds of children as they looked at works of art, specifically paintings hanging in the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. Francesco Walker, a cognitive psychologist who conducted the study while at VU University Amsterdam, and colleagues equipped nine children and 12 adults with eye-tracking headsets as they observed five paintings. The children were ages 11 and 12. Participants saw each painting twice, before and after hearing a description of the art. (You can watch a video explainer of the experiment here.)

When the children first viewed a Van Gogh painting, they focused on bold, bright colors and attention-grabbing objects: A striped house, vivid roses, dark trees painted against a light skyline.

The adults, in contrast, weren’t as drawn to the bright colors and attention-grabbing objects on their first (or second) looks. They focused more on other areas of the paintings.

The results, published June 21 in PLOS ONE, show that when children are given context about a painting they shift what they focus on while viewing it.

That switch in gaze represents an interesting switch in thinking, the researchers believe. The first type of viewing relies on “bottom-up” attention, in which the eye is drawn to whatever visually pops out. Walker describes this sort of looking as something involuntary, driven by the physical properties of an object or scene. The second sort of attention, called “top-down,” is more purposeful. “Top-down attentional control is driven voluntarily, by factors that are internal to the observer,” Walker says.

Looking for your friend in a crowd, holding a picture of her in mind, requires intentional searching. That’s a top-down task. But if you’re suddenly captivated by the sight of a monkey playing a tiny accordion, that would be a bottom-up diversion. Studies like this one on children and adults suggest that with age, “top-down processes become more and more important, while bottom-up attention loses strength,” Walker says.

In the absence of eye-tracking technology, I just asked my daughter what she saw. She started by naming colors: “Blue, green, brown.” After she ran through all of the hues, I asked if she saw anything else. She paused, considering the image carefully. “Is it dinosaurs?” she asked. I told her that it’s a painting of tangled, blue tree roots in the ground. “But that green part looks like a Tyrannosaurus,” she told me. As her little finger gestured toward my computer screen, I saw what she meant: A green T. Rex head, rising majestically from the roots.