Year in Review: A double dose of virus scares

MERS, H7N9 join list of potential pandemics

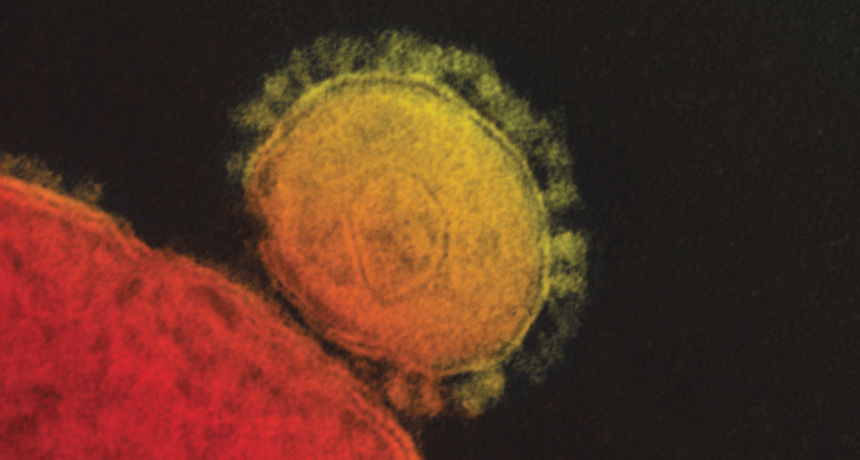

ACTIVE VIRUS A transmission electron micrograph shows the coronavirus responsible for Middle East respiratory syndrome in action.

NIAID

5

Outbreaks of two deadly viruses captured the world’s attention in 2013, but neither turned into the global pandemic expected to strike one of these years.

One of the viruses, known as MERS, causes Middle East respiratory syndrome. The other, H7N9, is a new bird flu virus from China. Each virus has infected fewer than 200 people, but both kill a sizable number of the people who contract them. Although the viruses have not spread far from where they started, the scientific effort to decipher and combat them has had global reach.

The MERS virus was first isolated from a patient in Saudi Arabia by an Egyptian physician who sent the sample to the Netherlands to be tested. There researchers in the lab of Ron Fouchier (who made headlines in 2012 for work on the bird flu virus H5N1) deciphered the MERS virus’s genetic makeup. It turned out that MERS is a coronavirus related to SARS, a virus identified in 2003 as the cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SN: 3/23/13, p. 5).

Since it first appeared in people in 2012, MERS has sickened 163 people, killing 71. Most of the victims live in Saudi Arabia, Qatar or the United Arab Emirates, or had recently traveled to the Arabian peninsula. H7N9, a new strain of avian influenza, began circulating in China in February. The outbreak peaked by early April, nearly halting after Chinese officials closed live poultry markets. Still, sporadic cases appeared in the summer and fall, raising concerns that the virus could make a resurgence in the coming flu season (SN Online: 10/15/13). By early December, of the 139 people with confirmed H7N9 infections, 45 had died.

It came as a surprise that this type of bird virus was seriously sickening and killing people. Experts have been worried for a long time that the H5N1 bird flu would sweep the globe as the 1918 Spanish flu did. If H5N1 gained the ability to spread from person to person through the air while retaining its potency, it could potentially kill millions. But until this year, no serious human infections with H7N9 had ever been recorded.

As more and more cases of MERS and H7N9 infection appeared, scientists and health workers scrambled to investigate basic questions about the viruses: Where did they come from? How did they get into humans? How do they infect cells? And perhaps most important, do they spread easily from person to person, becoming a candidate for a pandemic? Only partial answers have emerged, and some are not comforting.

Researchers found molecular handles on human cells that the MERS virus grasps during infection (SN Online: 3/13/13). One study revealed that H7N9 can grow well in human lung cells (SN Online: 7/3/13).

Studies of ferrets revealed that H7N9 can spread through the air from one of the animals to another, raising the possibility that it might also pass from person to person that way (SN Online: 5/23/13). But so far, the virus hasn’t been easily transmitted between people. A few people may have spread the virus to their relatives, but most people probably caught it from chickens, ducks, pigeons or other birds at live poultry markets (SN Online: 4/12/13, 4/15/13).

But the MERS virus does spread from person to person, particularly among people who are elderly or have other health problems. Hospital dialysis wards proved important for at least one big outbreak (SN Online: 6/19/13).

Researchers have been using DNA data and old-fashioned health sleuthing to track down the source of the MERS virus. It probably originated in bats and may have spread to camels and other animals before infecting humans (SN: 9/21/13, p. 18; SN Online: 8/8/13, 10/9/13). Whatever its origin, MERS probably made the leap from animals to people multiple times (SN: 10/19/13, p. 16). New cases of the virus continue to emerge, and there is ongoing concern that it could become a worldwide problem.