Gail Patricelli wasn’t so sure that courtship is really as one-sided as the ill-fated show “Who Wants to Marry a Millionaire?” where contestants strutted, and a watcher of the other sex selected. So, Patricelli decided to build a robot to find out.

The question of dating dynamics comes up in many species. However, Patricelli is sticking to satin bowerbirds. They make a lot of human strut-your-stuff behavior look positively restrained.

To illustrate the birds’ exuberance, Patricelli leads the way into a small, windowless room in the biology building at the University of Maryland in College Park. About 2,000 videotapes jam shelves from chin height to the ceiling: tapes from surveillance cameras hidden at bowerbird bachelor pads half a world away.

For more than a decade, Patricelli’s mentor at Maryland, behavioral ecologist Gerald Borgia, has been sending research teams to a forested valley in New South Wales, Australia. Each September-to-December mating season yields several thousand more tapes of bowerbird love life, which undergraduates review in the tape-lined room. They sort through humdrum hours—avian housekeeping, lizard visits, and birds peering into the camera lens—while waiting for the real action.

And what action it is. The males of this extraordinary bird family build special arenas where they perform in front of each female who drops by. Patricelli fires up one of the video monitors with a director’s cut of some recent seasons.

Pictures in bird books, even strings of diagrams, don’t prepare a viewer for the male bowerbird’s wacky intensity. When he finds a female settling into his bower—for most species, a small structure in a cozy forest clearing—he grabs a beakful of feathers from piles he’s accumulated and throws himself into a fast-forward, quick-change show. He shoots across his arena, buzzing like the death rattle of a small engine.

Then he poses, cawing perfect imitations of a crowd of cockatoos or a plaintive, far-away crow. With the abrupt changes of shtick and the tearing up and down, has some punk ’80s guitarist been reincarnated as a bowerbird?

Throughout the show, the female just sits in the bower. Well, Patricelli points out, she often crouches forward. The female’s most dramatic gesture, if she decides this guy’s the bird, comes when she crouches even further forward and fluffs her feathers into a receptive posture.

With all due respect, her part of the act’s not too exciting, and theorists have never assigned much of a role to her. Because male bowerbirds don’t provide parental care, these biologists say, What do you expect? Ornithologists generalize that only bird couples that share chick care perform interactive courtships. For them, each action invites an answering gesture in a duet negotiating the birds’ bond.

However, males of non-monogamous, or polygynous, species like bowerbirds mate with as many females as they can and don’t help raise the chicks. So, the females are just shopping for sperm, the common view holds. Males strut; females watch. No duet here.

Patricelli’s not so sure. She and some other bird behaviorists are rethinking the female’s role in polygynous courtship, and the satin bowerbird makes a great test species.

Patricelli’s suspicion that females and males do perform interactive courtships sparked a 4-year adventure in the outer fringes of the study of animal behavior. Patricelli wanted more than surveillance cameras. She wanted to direct the female’s behavior. She envisioned controlling a robot that could replace the female and fool a male completely. So, she created the fembot.

Bachelor pad

Patricelli’s work builds on decades of studies by Borgia’s team and other scientists illuminating courtship bowers. Of the world’s 18 species of bowerbirds, 14 court in a special bachelor pad that the male arranges.

The lower-tech species create lichen mats in small forest clearings, perhaps enhancing the romantic setting with a heap of snail shells. Another group of species organizes its bowers around a central sapling or some other sort of pole. For example, Macgregor’s bowerbirds mound small sticks around this upright to raise a doughnut platform. Vogeltop bowerbirds go even further, weaving small sticks into a tidy Polynesian-style hut around the center pole and adorning its grand entrance with flowers and shells.

Patricelli’s satin bowerbirds belong to a third school of architecture, the alley builders. They construct variations on a pair of thick, woven-stick walls, about knee-high to a birdwatcher, with a narrow passageway between them.

Despite the 2 or 3 months that the male spends building and tending his bower, no bird ever lives in one. The male doesn’t roost inside his bower. He’s too busy repairing it, defending it, and perching on nearby branches belting out songs to advertise it. When he rests, it’s in a tree.

Each of a succession of female birds flies into the bower for a few minutes—perhaps 15 if the male’s show turns out to be convincing—and then, she’s outta there. The fluttering consummation, if it occurs, takes maybe 3 seconds. After mating with a male, the female selects her own site to build a nest and raise chicks, without male assistance.

For all the effort a bower demands, why bother?

Scientists since Darwin have wondered about it. More than 20 years ago, biologist E. Thomas Gilliard contended that the bowerbird species in which males themselves flash colorful plumage tend to build simple structures, whereas the plainer birds create more highly decorated concoctions. This trend, he contended, supports the view that bowers serve as competitive sexual displays, perhaps versions of a peacock’s tail, with some assembly required.

Filming satin bowerbirds in New South Wales, Borgia and his students have tried to figure out what makes certain bowers—and the shows that go on at them—so attractive. For the bower system does make big winners and big losers, they report. In one tally of nearly 30 males, 10 never scored during the entire mating season, while one of their neighbors successfully strutted his way to fatherhood on 33 occasions.

Construction quality of the bower turns out to influence a male’s chances of success. “The funny thing is that you can tell, as a human, which are the good bowers,” Patricelli says. “The ones that I like, the female bowerbirds like too.”

A genuine bower, collected from the wild, adorns the top of the refrigerator in the laboratory where Patricelli works. Now a connoisseur of avian architecture, she praises the refrigerator-top bower as the work of a fine builder.

On tiptoe, she points out the uniformity of the several hundred dark, slender twigs massed to form the pair of gently curved walls. End on, they look like a pair of bottom-heavy, thatchy parentheses. Their gentle inside curve seems just right for cradling a female bird. The builder didn’t merely poke sticks into the ground but wove them into a firm mass, much like a bird nest. Another expert touch, Patricelli notes, shows in the symmetry of the two walls.

A male begins building at the age of 6, when he starts to get his dark, satiny, blue-black plumage. For the next year or two, his technique typically improves, but after about three seasons, he seems about as good a builder as he’s going to be.

A young male’s first attempt at a bower risks skimpiness and irregular form. Some junior builders find their bowers slumping over into a heap of sticks. “When they’re bad, they’re really, really bad,” Patricelli says.

Borgia’s team has also found that decoration affects a male’s chances of convincing a female to mate. Males strew their display court with blossoms, feathers, and knickknacks, particularly in shades of blue. Occasionally a male in a decorating frenzy flits into the cabin where the Borgia team lives and carries off trophies.

“We don’t even take blue toothbrushes there anymore,” Patricelli says. “It’s the one place in the world where when you lose a blue ball-point pen cap, you have a good idea where it is.”

Males steal from each other, too. The research teams number each decorative item at a bower and do a daily inventory. Blue feathers get stolen most frequently, the researchers report. The number of feathers displayed around a successful stud’s bower peaks at the height of mating season, just when the feather counts drop at the losers’ bowers.

The videotapes also reveal males flying into a rival’s bower when it’s unoccupied and trashing it. A marauder can do quite a bit of damage, ripping wads of sticks out of the walls and making off with prize decorations.

Hence, both Borgia and the team of Stephen and Melinda Pruett-Jones of the University of Chicago have proposed that well-built, abundantly ornamented bowers signal dominant males that can successfully defend their own territories and get away with harassing their neighbors.

Whatever it is that females are shopping for, they’re efficient at it, Patricelli and her Maryland colleagues J. Albert C. Uy and Borgia reported in the Feb. 7 Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B. Females that chose the local top studs, the males that racked up the most matings during the season, seemed to use that happy experience to shorten their future shopping. The next season, they just mated with Mr. Wonderful again. Females that had mated with lower-tier birds, however, made another shopping effort.

Scientists inventing theories about how birds shop for mates need to take caution from these bowerbirds, Patricelli urges. Models so far have largely ignored any carry-over effects from previous seasons, yet such memories seem likely to influence strategy in long-lived birds.

Female impersonator

A few years ago, while mulling over the problem of how to study interactions between courting birds, Patricelli took some videotapes over to University of Maryland robots expert Greg Walsh. He coaches the student team that took the world title in an annual international robot-jousting competition in Japan. So, Patricelli figured he’d be able to take in stride her request for a robot that could impersonate a female bowerbird.

“Of course, what I really wanted was one that would fly into a bower,” she reminisces. The lab nickname for her robot, the fembot, came from the scantily clad, electronic beauties that fooled espionage goofball Austin Powers in The Spy Who Shagged Me. However, Walsh and Patricelli agreed to lower their expectations to a robobird that could perform a few basic robomoves: turning its head, crouching, and extending its wings slightly away from its body.

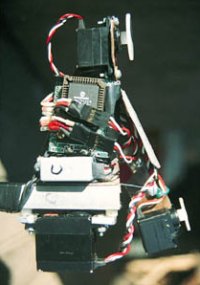

When Patricelli was in Australia setting up cameras for the 1997 breeding season, Walsh shipped her the unadorned guts of the first fembots. They’re an impressive monument to the power of human hope. As Patricelli holds a version up in the lab, it looks as if it could barely seduce an electric can opener, much less a bird. Nuts and bolts hold several small motors and a circuit board on a hand-size plate mounted on a metal stake.

“It’s lucky I had a degree in art,” Patricelli chuckles. Still, bringing that hunk of metal to life took months.

Walsh’s prototype had proportions more appropriate for a pigeon than a svelte bowerbird, so Patricelli trimmed as much extraneous metal as she could. Then, she wrapped the delicate machinery in a mummy shroud of waterproof tape and embarked on a frantic quest for the right material to make the bird body. After a lot of shopping and consultation with bemused sales staff in Australian craft stores, she discovered the wonders of the plastic backing used for cross-stitch.

Patricelli wove florist wire through the cross-stitch backing so the material would hold a shape. Then, she molded a skin of wired backing around the metal guts to form a bird body.

Satin bowerbirds abound in eastern Australia, pillaging vegetable gardens and picking through garbage for trinkets. So, Patricelli was able to obtain a feathered skin for the outer layer of her fembot. However, she still needed eyes—lilac-colored eyes, as a matter of fact. She sent a bowerbird photo to a taxidermy-supply company. “They did a pretty good job,” she says, holding up a finished fembot so the sun can catch its lavender beads.

To test her creation, Patricelli hid the fembot under a piece of denim and crept up to a bower while its owner was away. She poked the fembot’s stake into position in the bower alley, trailed the controlling wires back into the shrubbery, and then whisked off the denim cover to reveal—she hoped—a typical female bowerbird waiting for a show.

“I felt like I was I on a first date,” Patricelli says. Holding the fembot’s controls, she hid near the bower. Males often return to find a female in the viewing stand, so she hoped the situation would seem natural even though the female did have a stout metal stake coming out of her belly. “The prototype was pretty overweight,” Patricelli admits, but she hoped the male would be enthusiastic rather than discriminating.

When the male returned, he did indeed perform courtship antics for the fembot. The slight whirring of her head didn’t seem to throw off his performance. All went as Patricelli hoped, and when she twirled the control knobs to make the fembot bend forward in acquiescence, the male accepted the gesture as the consent he’d been dancing for.

In her Maryland lab, Patricelli deftly twists knobs on the robot’s control box to demonstrate the female’s gesture of acceptance. A male responding to the crouch dashes to the back of the bower for actual mating but gets a view of a protruding chunk of cross-stitch backing, florist wire, and machinery. Does this spoil the mood?

No, Patricelli reports, “at that point, he’s totally focused.”

In fact, the design was so successful that she often had to interrupt courtships, diving out of the bushes and shooing away the male, just to save wear and tear on the fembot.

Intense performance

Once Patricelli and Walsh had worked out the design, she fixed up three ready-to-flirt fembots. Patricelli and two colleagues spent the 1998 and 1999 bowerbird seasons testing male reactions to the speed at which the fembots crouch. Patricelli kept track of whether female gestures seemed to prompt a male to intensify his performance or to cool it down.

The rate of crouching does seem to set the pace for the performance. “The male is altering his display,” Patricelli concludes. The theme of customizing a male’s intensity echoes one of Borgia’s ideas, that a sheltering bower permits a male to act out aggressive gestures that arouse the female but don’t scare her so much that she flees (SN: 11/21/98, p. 326). Patricelli’s work adds more evidence for such an interaction.

That conclusion doesn’t particularly surprise another close observer of female birds, Meredith West of Indiana University in Bloomington. West has studied cowbirds for years, particularly the multiple songs of males.

A male cowbird may burble along, seemingly on his own, West notes. Yet the songs that come to predominate in his repertoire are those fragments that earn a female’s response. Her reaction may not be even remotely as showy as his, but her subtle gestures drive his song.

West’s tale from another species fuels Patricelli’s curiosity about other quiet female gestures that may have been overlooked. And yes, she thinks it would be great fun to study cowbirds with a female cowbot.