The universe’s first supernovas probably produced water

Water could have formed only a few hundred million years after the Big Bang

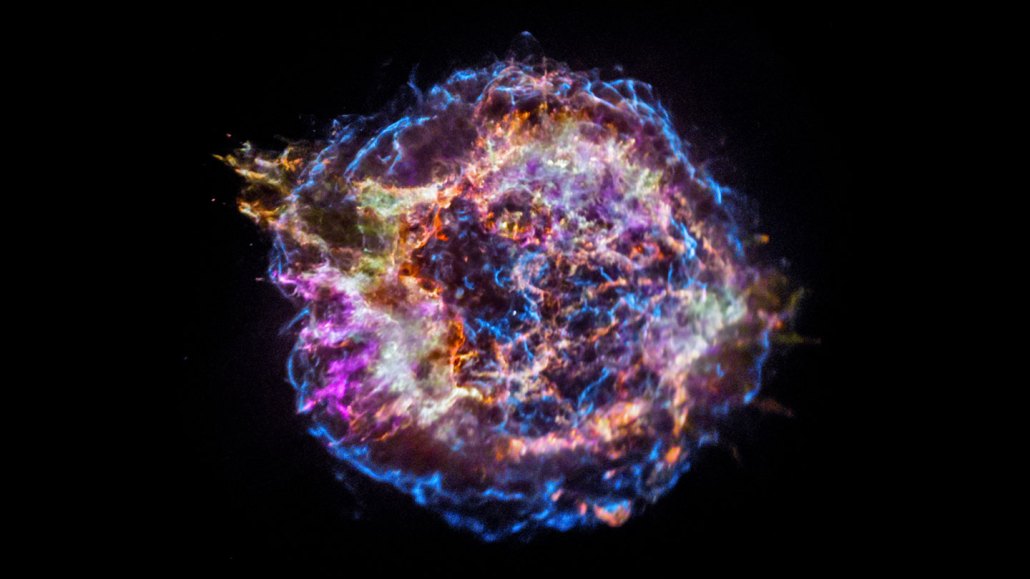

The supernova remnant Cassiopeia A (seen here in a false-color X-ray image) is all that remains of a star that exploded thousands of years ago in the Milky Way. Astronomers think supernovas just 100 million to 200 million years after the Big Bang could have produced water.

NASA, CXC, SAO

The first generation of stars in the universe could have produced significant amounts of water upon their deaths, just 100 million to 200 million years after the Big Bang.

Signatures of water have previously been observed some 780 million years after the Big Bang. But now, computer simulations suggest that this essential condition for life existed far earlier than astronomers thought, researchers report March 3 in Nature Astronomy.

“The surprise was that the ingredients for life were all in place in dense cloud cores [leftover after stellar deaths] so early after the Big Bang,” says astrophysicist Daniel Whalen of the University of Portsmouth in England.

Water may be common today. But in the beginning, roughly 13.8 billion years ago, the universe was essentially just hydrogen, helium and a little bit of lithium. It took stars to make the rest. Some midweight elements, such as carbon and oxygen, are fused inside of stars as they age. Others are forged in stellar deaths, such as explosive supernovas or the violent mergers of neutron stars. However, for more complex molecules to form in significant quantities, relatively dense and cool conditions, ideally less than a few thousand degrees Celsius, are needed.

“Water is a pretty fragile molecule,” says astronomer Volker Bromm of the University of Texas at Austin, who was not involved with the new research. “So the catch is, do we have conditions that can form it [very early in the universe]?”

To see if there could have been water in the infant universe, Whalen and his colleagues ran computer simulations of the lives and deaths of two first-generation stars. Because astronomers think early stars were much larger and had shorter lifespans than modern stars, the team simulated one star with 13 times the mass of the sun and another 200 times the sun’s mass. At the end of their short lives, these behemoths exploded as supernovas and flung out a shower of elements, including oxygen and hydrogen.

The simulations showed that as the supernovas’ ejected matter expanded and cooled, oxygen reacted with hydrogen and dihydrogen, or two joined hydrogen atoms, to make water vapor in the growing debris halos.

This chemical process proceeded slowly, since the density of atoms in the outer regions of the expanding supernova blasts was low. This low density means it was unlikely two elements would meet and hook up on short timescales.

But after a few million years — or tens of million years in the case of the smaller star — the dusty central cores of the supernova remnants had cooled enough for water to form. Water began amassing rapidly there since the densities were high enough for atoms to meet.

“[The water’s] concentration in dense structures, that to me is the game changer,” Whalen says. “The total overall mass of water being formed, it’s not that much. But it becomes really concentrated in the dense cores, and the dense cores are the most interesting structures in the remnant, because that’s where new stars and planets can form.”

At the end of the simulations, the smaller supernova produced a mass of water equivalent to a third of Earth’s total mass while the larger one created enough water to equal 330 Earths. In principle, Whalen says, if a planet were to form in a core leftover from the larger supernova, it could be a water world like our own.

“There seems to be an indication that the universe as a whole may have been habitable, if you like, already quite early on,” Bromm says. But water doesn’t get you all the way to life, he adds. “Then you start asking the question, [how early] can you combine carbon with hydrogen to get the molecules of life?”