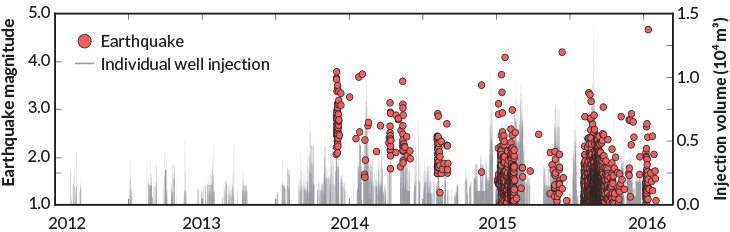

Volume of fracking fluid pumped underground tied to Canada quakes

Study shows fluid buildup, not injection rate, triggered hundreds of temblors around Fox Creek

PUMP DOWN Hydraulic fracturing operations pump a mix of water, sand and other materials into the ground to ease the retrieval of oil and gas from the rock layers. New research is looking into the link between fracking and earthquakes.

Doranjclark/iStockphoto