New baby pictures of the universe deepen a cosmic mystery

Cosmic expansion rate questions persist, but the standard cosmology model holds

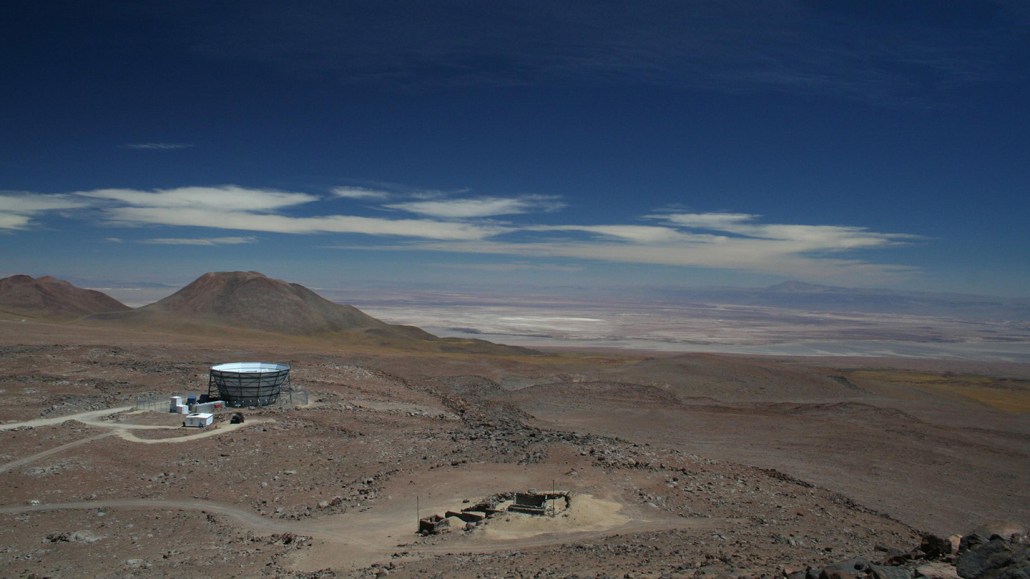

The Atacama Cosmology Telescope (pictured) in Chile is designed to gather intel on the cosmic microwave background, the thermal afterglow of the Big Bang.

Princeton University

The clearest pictures yet of the newborn cosmos strengthen the prevailing model of the universe but deepen a mystery about its expansion rate.

Measurements of this rate, known as the Hubble constant, have produced conflicting results. Cosmologists hoped that new data from the Atacama Cosmology Telescope in Chile, which examines the oldest light in the universe, would clear things up and possibly reveal physics that diverges from the standard model of cosmology. But those results, announced March 18 in a webinar, only affirmed that model.

“If you’d asked me to put a bet beforehand, I would have maybe put even money on seeing something new,” says cosmologist Colin Hill of Columbia University, a member of the telescope team. “But the standard model appears to reign supreme.”

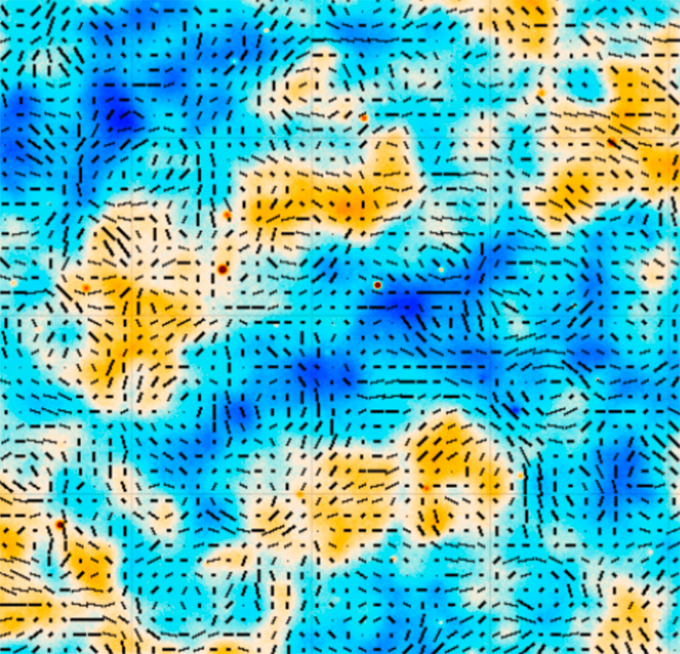

The Atacama Cosmology Telescope, or ACT, measured properties of the Big Bang’s thermal afterglow, known as the cosmic microwave background, with unprecedented sensitivity — particularly in the orientation of that light’s electromagnetic waves, or its polarization.

While previous telescopes mapped temperature fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background, indicating where matter was starting to clump together and foreshadowing the universe’s present-day structure, polarization maps put those clumps in motion.

“The polarization tells you how the gas and other matter that’s present in the early universe is actually moving around,” Hill says. That information allows cosmologists to project forward and see if it matches the current distribution of matter in the universe. “It gives us a much firmer prediction for what should happen in the next 13 billion years afterwards.”

The European Space Agency’s Planck satellite also measured polarization, but the larger ACT has five times the resolution, Hill says.

The newborn universe aligns with the standard Lambda Cold Dark Matter model, a relatively simple picture of the universe, the ACT team reports in three papers submitted March 18 to arXiv.org and a March 19 talk at a meeting of the American Physical Society in Anaheim, Calif.

Combined with previous results, the new ACT measurements, gathered from 2017 to 2022, confirm and refine many of the universe’s vital stats. It’s 13.77 billion years old and comprises 5 percent ordinary matter, 25 percent dark matter — which exerts gravitational attraction but otherwise doesn’t interact with regular matter — and 70 percent dark energy, a mysterious force pushing the universe to expand at an ever-accelerating rate.

The current expansion rate is 68.22 kilometers per second for each megaparsec (about 3 million light-years) of space, the team reports. That number agrees with previous measurements of the cosmic microwave background, such as those from the Planck satellite. But it disagrees with estimates based on closer objects, such as supernovas and the bright hearts of galaxies known as quasars, which have suggested a rate around 73 km/s/Mpc.

The discrepancy between the two types of measurements has been tightening for over five years. The ACT measurement turns the screws tighter.

Looking for a solution, the researchers examined several possible deviations from the standard model such as new particles, new interactions between dark matter and regular matter or itself, variations in fundamental constants or extra dark energy in the early universe. Nothing turned up.

“It just blew me away that we didn’t see even, like, a hint of one of these new physics extensions,” Hill says. “It indicates that we might need to go back really to some of the foundational assumptions of our understanding of cosmology.”

Other cosmologists may not have had such optimism about finding new physics, says physicist Daniel Scolnic of Duke University, who was not involved in the new work. “I think people expected that ACT wouldn’t see anything. But I did have a hope, so I was pretty disappointed,” he says. “But it’s okay. Nature will tell us the story.”

There’s still room for hope. The Simons Observatory, an even more sensitive telescope in Chile, started taking data in late February, which might find hidden deviations from the standard model.

“It could be the case that in a few years we will get some detection of new physics,” Hill says. “If we don’t keep looking, we won’t give ourselves a chance.”

Progress could also come from relaxing some of the standard model’s assumptions. Scientists have assumed, for example, that dark energy’s density has remained constant.

But a recent survey using the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument suggested that dark energy changes over time. That suggestion got stronger when the project announced on March 19 that an analysis of 14 million galaxies and quasars better matches a universe where dark energy evolves rather than one where it is static.

“If they confirm that at high significance, then we would really need to revisit a lot of our investigations,” Hill says. “It could open up avenues in the early universe that previously the data would not have allowed.”

Senior writer Emily Conover contributed to this story.