Trapping atoms in a laser beam offers a new way to measure gravity

The technique can measure slight gravitational variations, which could help in mapping terrain

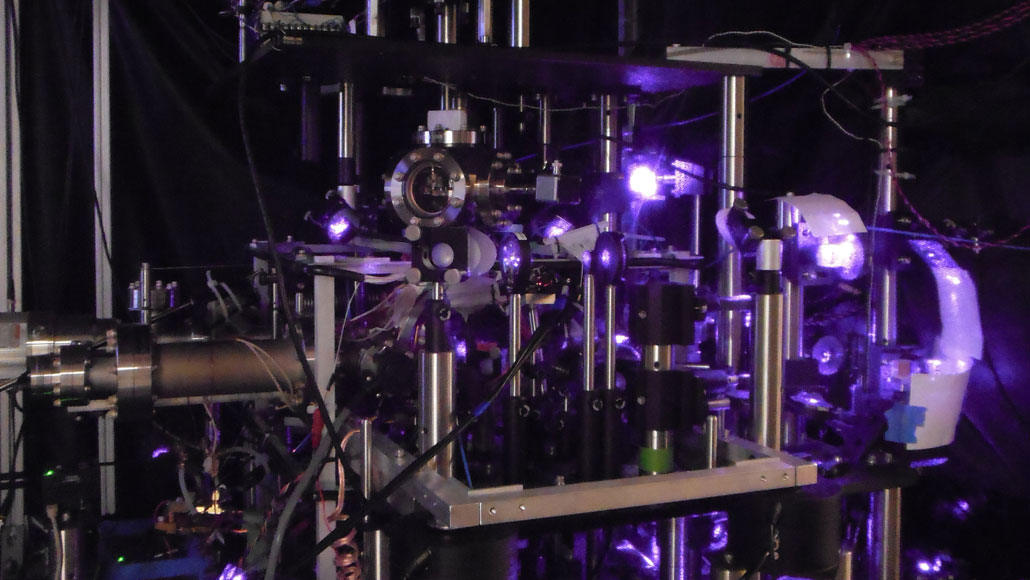

A new type of experiment to measure the strength of gravity uses atoms suspended in laser light (with the machinery pictured above), rather than free-falling atoms.

V. Xu

- More than 2 years ago

By watching how atoms behave when they’re suspended in midair, rather than in free fall, physicists have come up with a new way to measure Earth’s gravity.

Traditionally, scientists have measured gravity’s influence on atoms by tracking how fast atoms tumble down tall chutes. Such experiments can help test Einstein’s theory of gravity and precisely measure fundamental constants (SN: 4/12/18). But the meters-long tubes used in free-fall experiments can be unwieldy and difficult to shield from environmental interference such as stray magnetic fields. With a new tabletop setup, physicists can gauge the strength of Earth’s gravity by monitoring atoms suspended a couple millimeters in the air by laser light.

This redesign, described in the Nov. 8 Science, could better probe the gravitational forces exerted by small objects. The technique also could be used to measure slight gravitational variations at different places in the world, which may help in mapping the seafloor or finding oil and minerals underground (SN: 2/12/08).

Physicist Victoria Xu and colleagues at the University of California, Berkeley began by launching a cloud of cesium atoms into the air and using flashes of light to split each atom into a superposition state. In this weird quantum limbo, each atom exists in two places at once: one version of the atom hovering a few micrometers higher than the other. Xu’s team then trapped these split cesium atoms in midair with light from a laser.

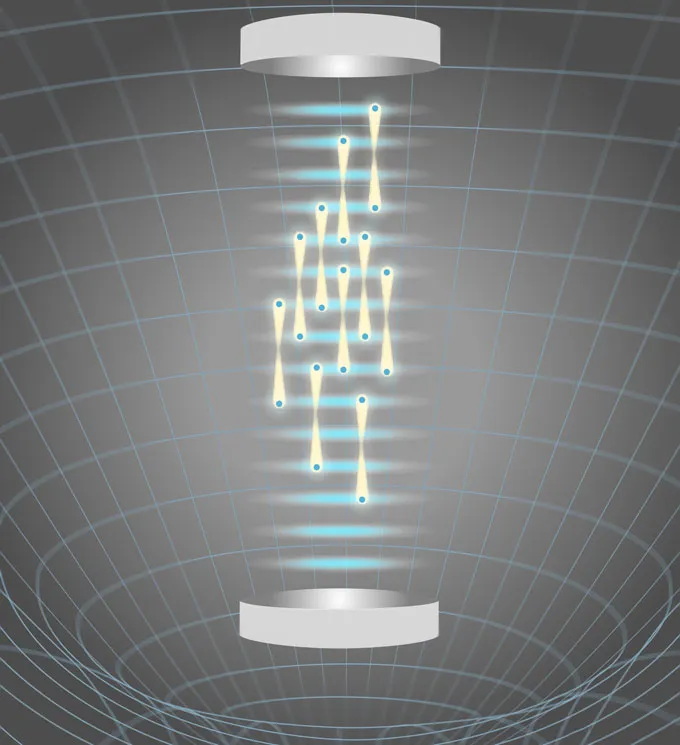

Got you, atom

To measure gravity, physicists split atoms into a weird quantum state called superposition — where one version of the atom is slightly higher than the other (blue dots connected by vertical yellow bands in this illustration). The researchers trap these atoms in midair using laser light (horizontal blue bands). While held in the light, each version of a single atom behaves slightly differently, due to their different positions in Earth’s gravitational field. Measuring those differences allows physicists to determine the strength of Earth’s gravity at that location.

Measuring the strength of gravity with atoms that are held in place, rather than being tugged downward by a gravitational field, requires tapping into the atoms’ wave-particle duality (SN: 11/5/10). That quantum effect means that, much as light waves can act like particles called photons, atoms can act like waves. And for each cesium atom caught in superposition, the higher version of the atom wave undulates a little faster than its lower counterpart, due to the atoms’ slightly different positions in Earth’s gravitational field. By tracking how fast the waviness of the two versions of an atom gets out of sync, physicists can calculate the strength of Earth’s gravity at that spot.

“Very impressive,” says physicist Alan Jamison of MIT. To him, one big promise of the new technique is more controlled measurements. “It’s quite a challenge to work on these drop experiments, where you have a 10-meter-long tower,” he says. “Magnetic fields are hard to shield, and the environment produces them all over the place — all the electrical systems in your building, and so forth. Working in a smaller volume makes it easier to avoid those environmental noises.”

Sign up for our newsletter

We summarize the week's scientific breakthroughs every Thursday.

More compact equipment can also measure shorter-range gravity effects, says study coauthor Holger Müller. “Let’s say you don’t want to measure the gravity of the entire Earth, but you want to measure the gravity of a small thing, such as a marble,” he says. “We just need to put the marble close to our atoms [and hold it there]. In a traditional free-fall setup, the atoms would spend a very short time close to our marble — milliseconds — and we would get much less signal.”

Physicist Kai Bongs of the University of Birmingham in England imagines using the new kind of atomic gravimeter to investigate the nature of dark matter or test a fundamental facet of Einstein’s theory of gravity called the equivalence principle (SN: 4/28/17). Many unified theories of physics proposed to reconcile quantum mechanics and Einstein’s theory of gravity — which are incompatible — violate the equivalence principle in some way. “So looking for violations might guide us to the grand unified theory,” he says. “That’s one of the Holy Grails in physics.”