Transplanted stem cells become eggs in sterile mice

Oocyte success raises hopes for infertility treatments

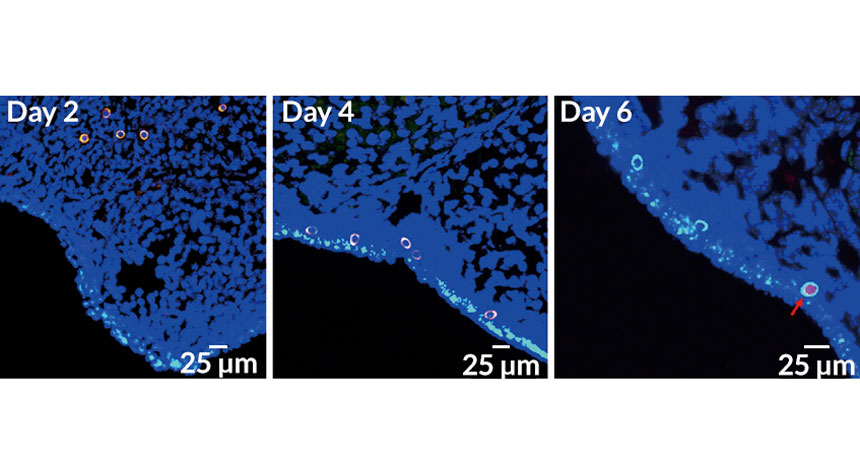

EGG-CITING DEVELOPMENT Germline stem cells (orange circles, left) implanted into a mouse’s ovary move to the edge of the ovary (middle) and begin developing into eggs. By day 6 (right) the cells began making a protein called STRA8 (pointed out with red arrow), one sign that they were starting to turn into eggs.

C. Wu et al/Molecular Therapy 2017