With Taxol, chromosomes divide and get conquered

New mechanism discovered for decades-old cancer drug

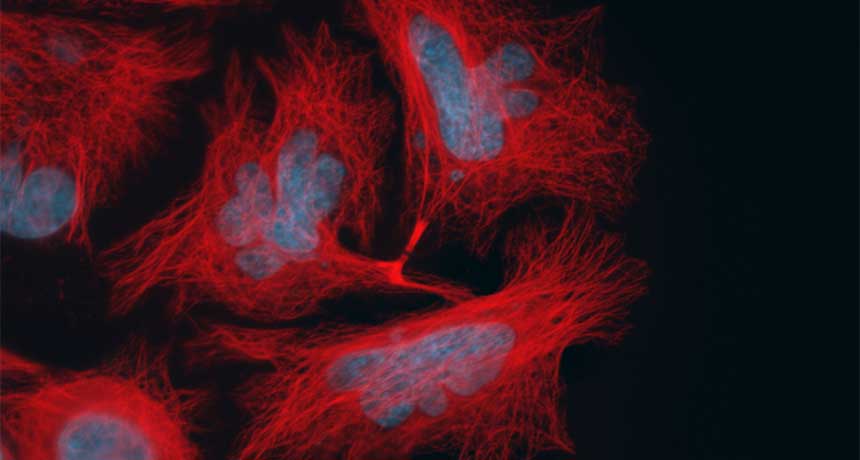

MIXED UP Human breast cancer cells from women treated with the chemotherapy drug paclitaxel abnormally split into more than two cells (shown in a micrograph, with alpha-tubulin, a protein involved in cell division, in red and DNA in blue). The progeny cells have jumbled chromosomes and tend to die.

Lauren M. Zasadil and B. A. Weaver