Suicide rates drop in big cities

With more social connections, people may be less inclined to take their own lives

SUICIDE IN THE CITY Big Brazilian cities (São Paulo, shown) tend to have lower suicide rates than smaller cities. A larger pool of social connections in bigger cities could help sustain city dwellers’ mental health.

Ndecam/Flickr

City living could curb suicides. As populations grow, suicide rates tend to dwindle, according to a new analysis of deaths in Brazil and the United States.

And there’s no minimum size that cities have to hit before seeing the improvements, says study coauthor Hygor Piaget Melo, a physicist at the Federal University of Ceará in Brazil. When comparing any two cities, he says, the one with more people will typically have a lower suicide rate.

The authors are the first to draw such a direct link between city size and suicides, says physicist Luis Bettencourt of the Santa Fe Institute. “They make it crystal clear.”

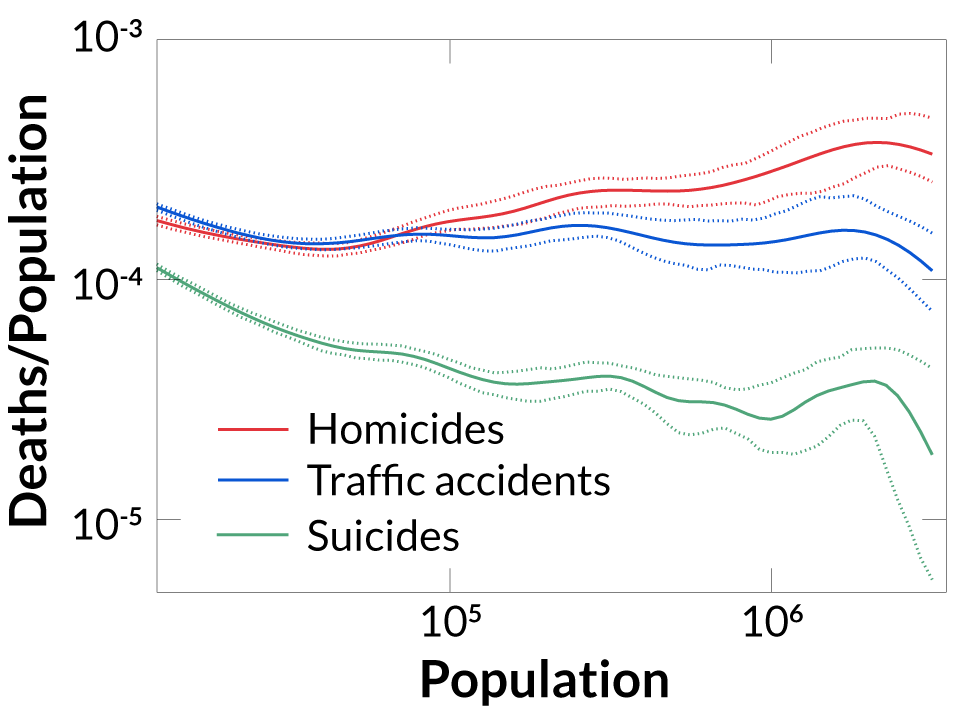

Scientists generally expect everything in a city, such as the number of companies, houses and jobs, to scale with population size. But some things don’t track population so neatly. Wages tend to increase faster than city growth. Squeezing lots of people into small spaces can also incite violence: In big cities homicide rates ramp up quickly.

Cities’ influence on suicides has been less clear. Melo, José Andrade Jr., also of the Federal University of Ceará, and colleagues compared the populations of some 5,000 Brazilian cities with official records of the number of suicides, homicides and traffic deaths in each city. The cities in the study were not defined by population but by administrative and governmental divisions, somewhat analogous to U.S. counties.

As expected, big cities had higher homicide rates than smaller ones. And though the number of traffic deaths doubled when city populations did, the number of suicides increased by only about 78 percent.

The researchers saw a similar dip in suicide rates when comparing large and small U.S. counties, they report February 11 in a paper at arXiv.org.

In cities, “more people are in your face” than in rural areas, Bettencourt says. “You have more social connections — people you work with, people you buy coffee from.”

Though these connections can be superficial, more mingling may somehow help city dwellers avoid thoughts of taking their own lives, Melo says.

“But this is very, very difficult to prove,” he adds. Other factors could also play a role, such as better access to hospitals and therapy.

Harvard mathematical biologist Alison Hill agrees. “It’s hard to disentangle all the factors,” she says. “It could be that people who are less prone to suicide move to big cities.”

Bettencourt thinks that looking at total death rates in addition to suicides, homicides and traffic deaths could help put suicide rates into context.

Still, the findings might foster better strategies for dealing with suicide, says physicist Haroldo Ribeiro of the State University of Maringá in Brazil. Antisuicide campaigns might take different tacks in large and small cities, he says.