Some people may have genes that hamper a drug’s HIV protection

Newly discovered genetic variants could explain why a common medication doesn’t protect all

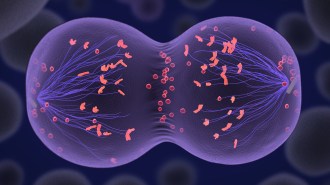

RESULTS MAY VARY Genetic variants may stymie how well the antiretroviral drug tenofovir works in some people.

NIAID/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)