Small doses of peanut protein can turn allergies around

Most kids in a clinical trial could tolerate the equivalent of two large nuts after a year

ALLERGY RELIEF Allergic children exposed to gradually increasing doses of peanut protein were eventually able to tolerate the equivalent of two nuts, a study finds.

inewsistock/iStock.com

Carefully calibrated doses of peanut protein can turn extreme allergies around. At the end of a year of slowly increasing exposure, most children who started off severely allergic could eat the equivalent of two peanuts.

That reversal, reported November 18 in the New England Journal of Medicine, “will be considered life-transforming for many families with a peanut allergy,” says pediatric allergist Michael Perkin of St. George’s, University of London, who wrote an accompanying editorial in the same issue of NEJM. The findings were also presented on the same day at the annual meeting of the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology in Seattle.

Peanut exposure came in the form of a drug called AR101, described in the study as a “peanut-derived investigational biologic oral immunotherapy drug,” or, as Perkin puts it, “peanut flour in a capsule.” Unlike a sack of peanut flour, AR101 is carefully meted out, such that the smallest doses used in the study contained precisely 0.5 milligrams of peanut protein — the equivalent of about one six-hundredth of a large peanut.

In the clinical trial, 372 children ages 4 to 17 years began taking the lowest dose of AR101. The doses increased in peanut protein every two weeks until the kids topped out at 300 milligrams, which is about that of a single peanut.

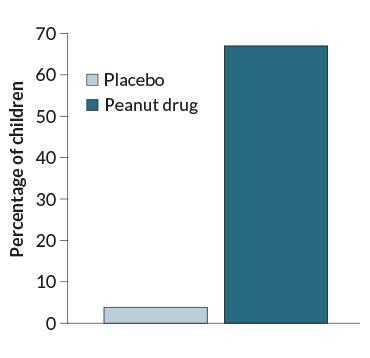

For the next 24 weeks, participants, located in the United States, Canada and Europe, took that dose daily. When the trial ended, all of the participants were challenged with increasing doses of peanut protein under close supervision. Two-thirds of the 372 children who received the peanut protein regimen, or 250 participants, could tolerate a peanut protein dose of at least 600 milligrams, comparable to about two peanuts. In contrast, only five of the 124 children who received placebos, or 4 percent, could tolerate the same dose. (A smaller number of adults ages 18 to 55 were enrolled in the study, but didn’t show big improvements.)

That improved tolerance “can really change the lives of patients who are peanut allergic,” says study coauthor Daniel Adelman, an allergist and immunologist at Aimmune Therapeutics, a company based in Brisbane, Calif., that makes AR101 and sponsored the trial.

The goal of the therapy is to guard against the potentially dangerous effects of accidental peanut exposures, such as a child mistakenly taking a bite of a friend’s PB&J. “What we’re trying to do is free people up from the fear and anxiety associated with the potential bad things that can happen with minute quantities of peanut exposure,” Adelman says.

During the study, nearly all of the participants who received the drug had allergic reactions to it — reactions that were expected, since “you’re giving people the thing they’re allergic to,” Adelman says. Most of those reactions weren’t severe, such as a rash or slight abdominal pain.

Although the drug is made of peanut protein, parents, or even doctors, shouldn’t attempt a similar treatment by measuring peanut protein themselves, experts say. Without exact measurements, peanut exposure could be dangerous. “This is treating peanut like a medicine, not a food,” says pediatric allergist Scott Sicherer of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City. “Don’t try this at home.”

Sicherer also cautions that, while the regimen is promising, it is not a cure. It’s not yet clear how long people would need consistent peanut protein exposure to maintain their tolerance, but regular use is probably needed. “It has to be a routine,” he says.