Slow sperm may fail at crashing ‘gates’ on their way to an egg

Narrow spots in the female reproductive tract could help weed out less desirable suitors

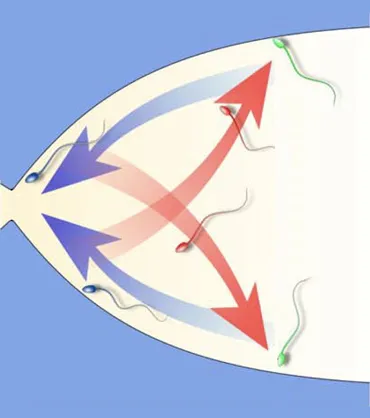

SWIM MEET Sperm face many obstacles along the way to an egg, including narrow points in the female reproductive tract that help sort out the top swimmers.

Panther Media GmbH/Alamy Stock Photo

The female reproductive tract is an obstacle course that favors agile sperm. Narrow straits in parts of the tract act like gates, helping prevent slower-swimming sperm from ever reaching an egg, a study suggests.

Using a device that mimics the tract’s variable width, researchers studied sperm behavior at a narrow point, where the sex cells faced strong head-on currents of fluid. The faster, stronger swimmers started moving along a butterfly-shaped path, keeping them close to the narrow point and upping the chances of making it through. Meanwhile, slower, weaker swimmers were swept away, the team reports online February 13 in Science Advances.

“Narrow junctions of the tract may act as barriers” to poor swimmers, says coauthor Alireza Abbaspourrad, a biophysicist at Cornell University. The results suggest that this is a way that females select the healthiest sperm, he says.

Sperm travel through the reproductive tract — the vagina, cervix, uterus and fallopian tubes — by swimming upstream against fluid flowing through the tract, which moves at different speeds along the way. Previous studies have shown that sperm tend to follow the walls of the tract to “steer” toward the egg, but haven’t investigated what effect the narrow spots might have on the trek.

Through computer simulations and tests of sperm, Abbaspourrad and colleagues found that the fastest sperm, when stopped by the current at a narrow point, could make it back to a wall, swim along it and try again. Repeated, this movement resulted in a butterfly-shaped pattern. Whether a swimmer could get through ultimately depended on the speed of the fluid through the narrow point and the speed of a sperm.

Most studies have tended to use devices with long, straight swimming channels “that effectively test endurance” of sperm, says David Sinton, a mechanical engineer at the University of Toronto who was not involved in the research. But at the narrow spots, the fluid flows faster than at wider parts, so sperm, in essence, need to sprint to get past. Investigating how sperm move in a device like the researchers used “tests both endurance and sprinting,” he says, and “I expect both abilities are needed” inside the female reproductive tract.