Skeleton ignites debate over whether women were Viking warriors

DNA analysis of bones buried with full battle gear identified as female

VIKING RETHINK A woman from the Viking Age in Sweden, when raids such as this were launched, may have shattered gender barriers by becoming a warrior who was buried with weapons and horses, researchers report. Their controversial conclusion has stimulated debate over the roles of Viking women.

ZU_09/iStockphoto

Viking warriors have a historical reputation as tough guys, with an emphasis on testosterone. But scientists now say that DNA has unveiled a Viking warrior woman who was previously found in a roughly 1,000-year-old grave in Sweden. Until now, many researchers assumed that “she” was a “he” buried with a set of weapons and related paraphernalia worthy of a high-ranking military officer.

If the woman was in fact a warrior, a team led by archaeologist Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson of Uppsala University in Sweden has identified the first female Viking to have participated in what was long considered a male pursuit.

But the new report, published online September 8 in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology, has drawn criticism from some researchers. All that’s known for sure, they say, is that the skeleton assessed in the new report belonged to a woman who moved to the town where she was interred after spending her youth elsewhere.

“Have we found the Mulan of Sweden, or a woman buried with the rank-symbols of a husband who died abroad?” asks archaeologist Søren Sindbæk of Aarhus University in Denmark. There’s no way to know what meanings Vikings attached to weapons placed in the Swedish grave, Sindbæk says.

Although the new paper dubs the long-dead woman “a high-ranking female Viking warrior,” other interpretations of her identity are possible, Hedenstierna-Jonson acknowledges. But she notes that the Viking woman “was an exception in a sphere dominated by men, either if she was an active warrior or if she was ‘only’ buried in full warrior dress with a complete set of weapons.”

Excavations in the late 1800s at Birka, a Scandinavian trading center from the 700s to around 1000 (SN: 4/18/15, p. 8), uncovered the woman’s grave. Remains of Birka lie on the island of Björkö, about 30 kilometers west of present-day Stockholm. About 1,100 of more than 3,000 graves that encircle Birka have been unearthed.

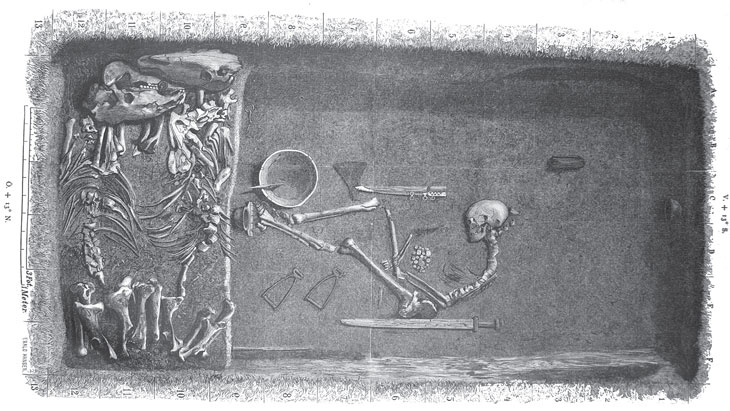

Excavators noted that the body lay among a warrior’s gear. This equipment included an ax, a spear, arrows, a large knife, two shields and two horses. Playing pieces found in the grave, apparently for some type of board game, suggest the woman may have been a high-ranking officer with knowledge of military tactics and strategy, Hedenstierna-Jonson’s team speculates.

Story continues below image

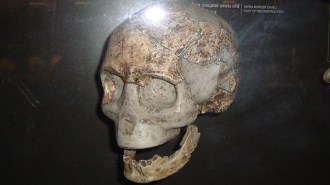

Fighting woman

An illustration based on the original excavator’s description of a 10th century Swedish grave shows a human skeleton — now identified as female — placed near weapons, gaming pieces and two stirrups. Bones of a pair of horses lie on the grave’s left side. Some scientists suspect the grave held a Viking warrior woman, but that’s a controversial view.

Researchers have typically assumed that Viking-era graves with weapons contain male warriors. Curiously, though, many skeletons in these graves, including that of the Birka woman, display no battle injuries.

Biological anthropologist Anna Kjellström of Stockholm University, a coauthor of the new study, reported at a meeting in 2013 that the Birka individual was a woman, based on pelvic shape and bone sizes. DNA from the Birka skeleton now confirms its female status and reveals many genetic similarities to present-day northern Europeans.

A comparison of two forms of radioactive strontium in teeth from the Birka woman, 15 other individuals excavated at Birka and pre-Viking age people from several parts of Sweden indicated that the woman moved to the trading center as a teenager or young woman. Humans absorb strontium from local rock formations through water and plant foods, leaving a chemical signature in teeth that approximately maps where these people grew up. The researchers estimate the woman was at least 30 years old when she died.

Findings in the new paper don’t demonstrate that the Birka woman was a Viking warrior, writes archaeologist Judith Jesch in a Sept. 9 post on her Norse and Viking Ramblings blog. Perhaps all alleged warriors in Viking-era warrior graves who lack serious wounds didn’t actually fight, contends Jesch, of the University of Nottingham in England. Hedenstierna-Jonson’s group provides no evidence that the Birka woman’s bones contain traces of strenuous physical activity expected from a warrior adept enough to avoid severe injuries, she writes.

“A certain amount of confusion” surrounds the original locations of bones excavated at Birka and then bagged for storage, including those of the proposed woman warrior, Jesch adds. Sloppy excavation practices at Birka more than 100 years ago sometimes accidentally lumped together bones from different graves, she says in her post.

Women could have been warriors during the Viking age, whether or not the Birka woman fought alongside men, says archaeologist Marianne Moen of the University of Oslo. Research over the past 30 years shows that Viking women were landowners, farmers, merchants, traders and participants in legal proceedings. Graves of two other Viking-era women, both in Norway, contain various weapons.

What’s important is not to hold women to a different standard than men when assessing comparable weapons placed in their graves, Moen asserts. The Birka find “was a warrior grave until it was sexed as female,” she says. “Now a lot of people would like to call it something else. That is where the danger lies here.”