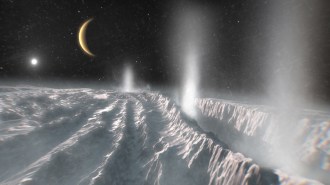

Seismic experiment might reveal thickness of Europa’s ice

Scientists propose crashing empty fuel tank into Jupiter moon

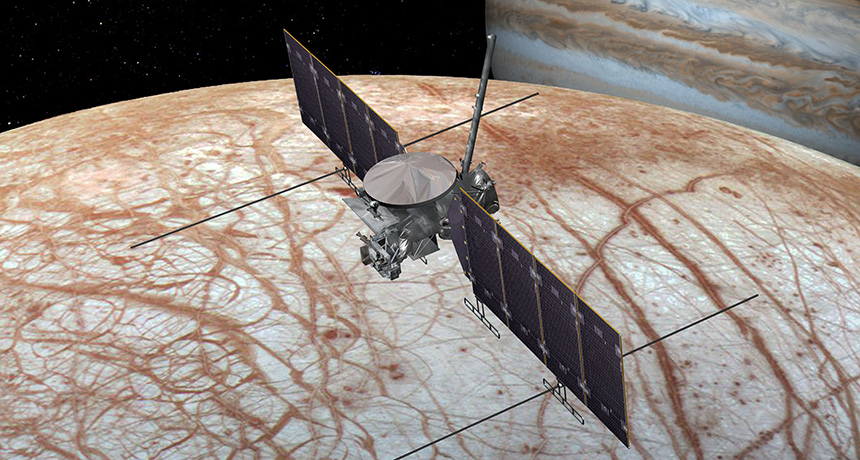

TARGET: EUROPA Slamming a spent fuel tank into the surface of Jupiter’s icy moon Europa could vibrate the surface so much that a spacecraft flying by (shown in artist’s illustration) could see the tremors. Scientists might be able to analyze the tremors to gauge the thickness of the ice.

NASA/JPL-Caltech