Scented naps can dissipate fears

People unlearned an odor's unpleasant accompaniment when they smelled it in their sleep

Xiaphias/Wikimedia

- More than 2 years ago

A nap can ease the burden of a painful memory. While fast asleep, people learned that a previously scary situation was no longer threatening, scientists report September 22 in Nature Neuroscience.

The results are the latest to show that sleep is a special state in which many sorts of learning can happen. And the particular sort of learning in the new study blunted a fear memory, a goal of treatments for disorders such as phobias and post-traumatic stress disorder.

“It’s a remarkable finding,” says sleep neuroscientist Edward Pace-Schott of Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital.

Katherina Hauner and Jay Gottfried of Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine and their colleagues first taught 15 (awake) volunteers to fear the combination of a face and odor. Participants saw a picture of a certain man’s face and at the same time smelled a distinctive scent, such as lemon. This face-odor combo was paired with a nasty shock, so that the volunteers quickly learned to expect something bad when they saw that particular face and smelled the associated odor.

Then the volunteers tucked in for a nap in the laboratory. When the participants hit the deepest stage of sleep, called slow-wave sleep, Hauner and her colleagues redelivered the smell that had earlier come with a shock.

During the nap, some participants had learned that the smell was safe. The volunteers sweated less (a measure of fear) when the face-odor combination appeared after the nap, the scientists found. When the odor wasn’t presented during sleep, volunteers’ responses to the associated face were unchanged.

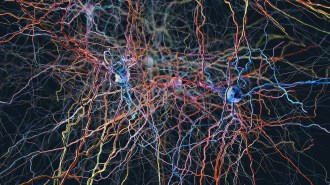

Upon awakening, volunteers also underwent scans that revealed changes in brain activity that accompanied this relearning. Odor exposure while sleeping seemed to cause neural changes in the hippocampus, a memory center, and the amygdala, which is linked to emotions.

This relearning process is similar to exposure therapy, Hauser says. In that type of therapy, a person with arachnophobia, for instance, confronts spiders over and over again until new memories of safety override the previous memory of fear. Exposure therapy is often very difficult for people, says neuroscientist Asya Rolls of Technion–Israel Institute of Technology. A treatment that could happen entirely during sleep, while the patient has no conscious knowledge of it, might be easier on people, she says. “These are very promising findings,” she says, “and I am excited to see how the field develops.”

Hauner says that it’s too soon to say whether the technique might help patients. Scientists need to test whether the fear memory could be weakened even more with longer sleep times and whether the benefits last, she says.

Editor’s Note: This story was updated on September 23, 2013, to add a study coauthor’s name.