SUN BLOCK A total solar eclipse (one shown from 2012) is one of nature’s most awesome spectacles. In advance of one that will sweep across the United States in August, publishers are releasing a spate of new solar eclipse books.

NASA Goddard Spaceflight Center/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

In August, the United States will experience its first coast-to-coast total solar eclipse in nearly a century. Over the course of an hour and a half, the moon’s narrow shadow will slice across 12 states, from Oregon to South Carolina (SN: 8/20/16, p. 14). As many as 200 million people are expected to travel to spots where they can view the spectacle, in what could become one of the most watched eclipses in history. Excitement is building, hence the flurry of new books about the science, history and cultural significance of what is arguably one of Earth’s most awesome celestial phenomena.

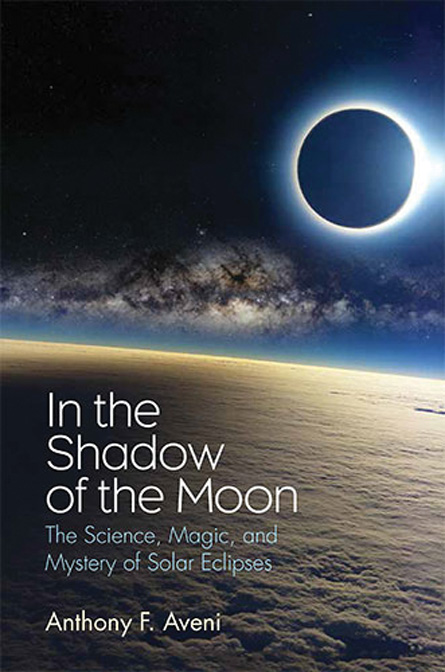

Total solar eclipses happen when the moon passes in front of the sun as seen from Earth, and the moon blocks the entire face of the sun. This event also blocks sunlight that would otherwise scatter off the molecules in our atmosphere, reducing a source of glare and so allowing an unfettered view of the sun’s outer atmosphere, or corona. Total solar eclipses arise from a fluke of geometry that occurs nowhere else in the solar system, astronomer Anthony Aveni explains in In the Shadow of the Moon. Only Earth has a moon that appears, from the planet’s viewpoint, to fit so neatly over the sun — a consequence of the fact that the sun is a whopping 400 times as large as the moon but also 400 times farther away. Moons orbiting other planets are either too small to fully cover the sun’s face or are so large that they fully block any view of the corona.

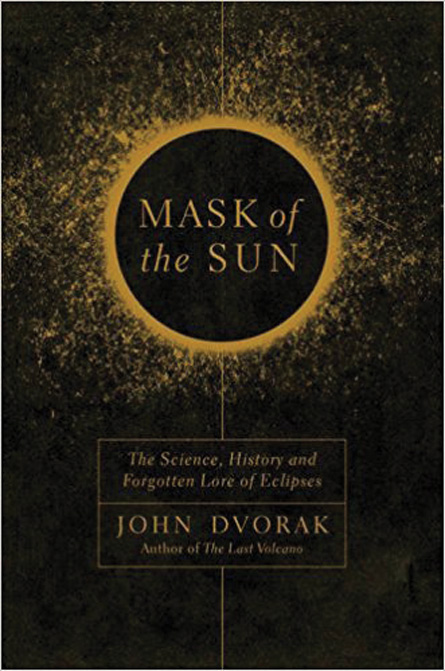

In fact, the fluke of geometry is also a fluke of history: Because the moon’s orbit drifts about four centimeters farther from Earth each year, there will come a time when the moon will no longer appear to cover the sun, notes planetary scientist John Dvorak in Mask of the Sun. We already get a preview of that distant day: When the moon passes in front of the sun during the most distant portions of its orbit (and thus appears its smallest), Earth is treated to a ring, or annular, eclipse.

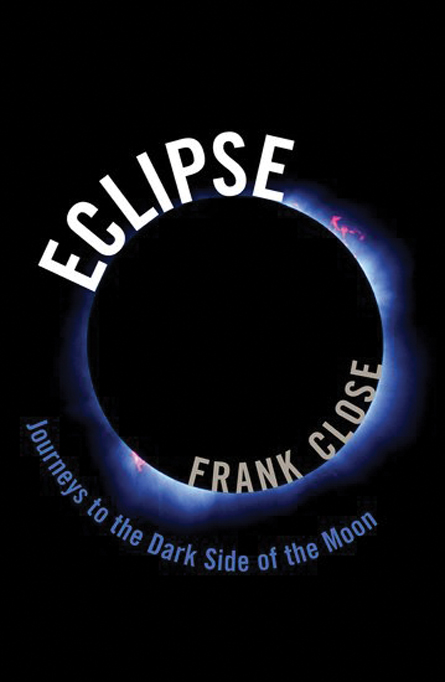

In the Shadow of the Moon, Mask of the Sun and physicist Frank Close’s Eclipse all do a good job of explaining the science behind total solar eclipses. That includes clarifying why one is seen somewhere on Earth once every 18 months or so, on average, instead of every time the moon crosses paths with the sun during the new moon. In short, it’s because the moon’s orbit is slightly tilted compared with Earth’s orbit around the sun, making the moon pass either above or below the sun during most new moons.

Many solar eclipses are preceded by a lunar eclipse about two weeks earlier — a coincidence that may have helped ancient astrologers “predict” an eclipse, Close writes. Additional observations, Dvorak notes, may have helped these nascent astronomers notice the long-term pattern in solar eclipses with similar paths, which tend to recur roughly every 18 years. While ancient Babylonians could predict the onset of a solar eclipse within a few hours — and ancient Greeks to within about 30 minutes — today’s astronomers can pin down eclipses to within a second.

That precision has fueled the craze of “eclipse chasing,” in which scientists and nonscientists alike trek to often remote regions to gather data or to simply experience the brief darkness — rarely more than seven minutes, and sometimes less than one second — of totality. In 1925, scientists chased an eclipse with an airship; in 1973, they did so at supersonic speed in a Concorde. All three books describe in detail various historical expeditions to view eclipses, everywhere from New York’s Central Park to exotic hot spots such as the South Pacific and Pike’s Peak in Colorado (which was pretty remote and exotic in 1878).

Each book shares many of the same anecdotes and recounts many of the same scientific breakthroughs that resulted from eclipse research. Both In the Shadow of the Moon and Mask of the Sun take readers on a largely chronological path through eclipse history. But their organizations differ slightly: The science of eclipses is deftly scattered throughout Mask of the Sun, while In the Shadow of the Moon addresses various scientific topics in wonderfully thorough chapters of their own.

Of this trio of books, Eclipse — more a memoir of Close’s lifetime fascination and personal experiences with eclipses than a detailed chronicle of historical lore — provides the most amusing and insightful descriptions of eclipse chasers. They are, Close writes, “an international cult whose members worship the death and rebirth of the sun at moveable Meccas, about half a dozen times every decade.”

A teacher kindled Close’s love of eclipses in 1954 when Close was an 8-year-old living north of London. He reached his 50s before experiencing a total eclipse (1999 in extreme southwestern England), but since then has seen a handful more, including from a cruise ship southwest of Tahiti and a safari camp in Zambia.

Who knows how many budding young scientists the Great American Eclipse of 2017 — or these books — will inspire.

Buy In the Shadow of the Moon, Eclipse or Mask of the Sun from Amazon.com. Sales generated through the links to Amazon.com contribute to Society for Science & the Public’s programs.

In the Shadow of the Moon

In the Shadow of the Moon Eclipse

Eclipse Mask of the Sun

Mask of the Sun