There’s more to pufferfish than that goofy spiked balloon

Pufferfish can have frenzied romantic lives, not to mention strange teeth

LIFE AS A WATER BALLOON The odd biology of pufferfishes (Japanese grass species shown) goes far beyond rapid swelling into a spiky balloon.

G. Fraser

So what if fish need water to live. For certain pufferfish, flirting on the sand of a moonlit beach is irresistible (in bursts). And that’s not the only odd thing the ocean’s famous self-inflators do.

Some of the 200 or so species in the puffer family take courtship to extremes. On a few moonlit nights a year at some Asian shores, Japanese grass pufferfish (Takifugu niphobles) flock to the beach to mate.

“A big ball of these pufferfish, maybe 400 fish, will sort of rise up on the rising tide and beach themselves,” says Gareth Fraser, an evolutionary developmental biologist at the University of Florida in Gainesville. Typically, that ball contains several hundred males and maybe one female, he says. The males start jumping around, releasing sperm onto the watery sand where a female discharges eggs. When a wave eventually sloshes in high enough, it washes them back to sea.

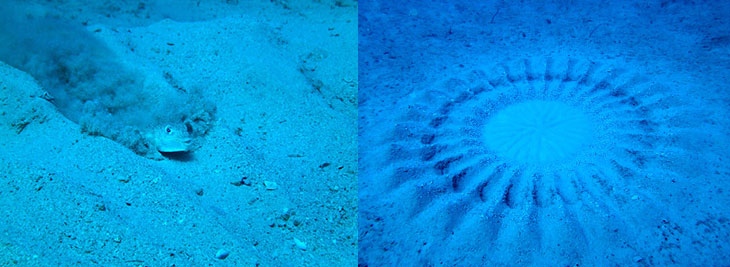

Sand underwater holds allure as well. Males of a species not recognized until 2014 turned out to be the architects of mysterious underwater versions of crop circles. These white-spotted pufferfish (Torquigener albomaculosus) spend days plowing and fin flapping sand into great symmetrical rosettes as welcome mats for female visitors.

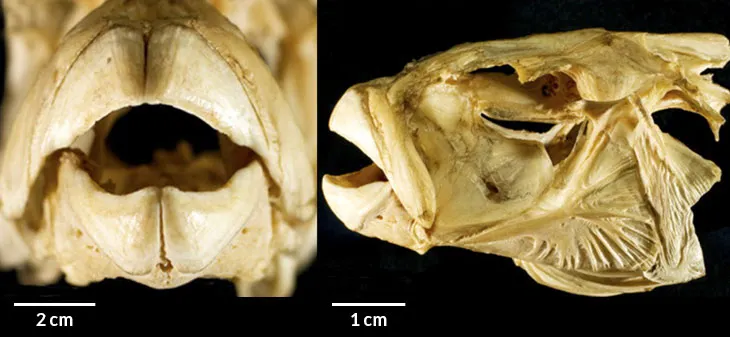

Courtship among some in the pufferfish family, however, can be pretty brutal, Fraser says. “Sometimes, the male will bite with these really sharp beaks on the abdomen of the females.”

It was those strange beaks, more parrot than shark, that first nibbled Fraser’s scientific curiosity. The first teeth in baby puffers seem unremarkably vertebrate. But as the young fish grow up, the rows of pointy bits gives way to two nubs that stretch sideways along the jaw, eventually creating a pair of long, sharp-edged blades. With one set of blades along the upper jaw and another on the lower, adult puffers “can chop a fish in half and then feast on it,” he says. Aquarists need to feed their pufferfishes plenty of hard-shelled mollusks to wear down the blades or trim them back with a fish version of a nail clipper. If the beaks overgrow, the fish can’t eat.

In the intimidating body part catalog, pufferfishes are perhaps best known for turning into spiky balls when outraged. These spines perk upright when puffers gulp water to balloon out their abdomens. Some of the same gene networks that put feathers on birds and hairs on mammals turn out to put the protective spines on puffers, Fraser and colleagues report July 25 in iScience. Those spines have evolved from the scales that covered distant fish ancestors. But between today’s skinny spines, modern pufferfishes are totally naked. Try not to stare.