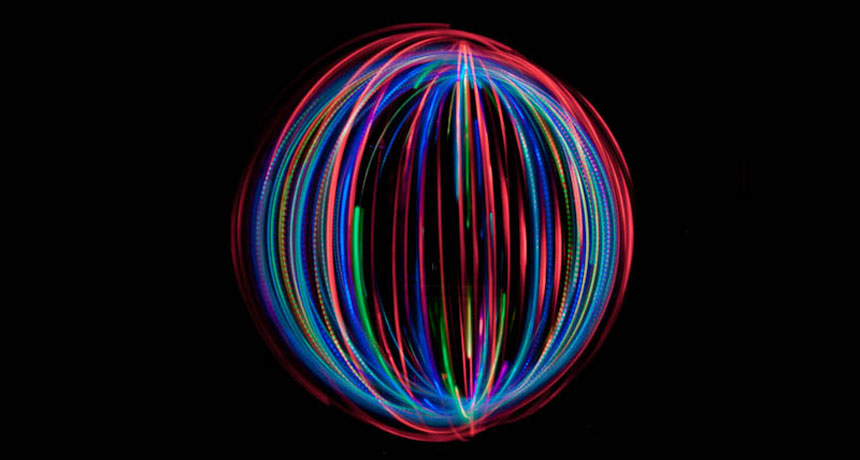

How a proton gets its spin is surprisingly complicated

In an odd twist, rarer up antiquarks add more angular momentum than more plentiful down antiquarks

SPIN SURPRISE Protons are composed of smaller particles, called quarks and antiquarks, which contribute angular momentum, or spin. Now scientists report that a rarer type of antiquark adds more to the proton’s spin than a more common variety.

Pryere/Flickr.com (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)