Pluto may have captured its moon Charon with a kiss

The pair of Kuiper belt objects linked up in a “kiss-and-capture” collision

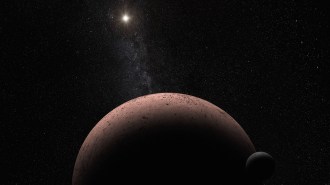

The New Horizons spacecraft flyby in 2015 captured these images of Pluto (lower right) and its large moon Charon (upper left). While this is a composite, and not to scale, new simulations reveal the pair’s close relationship.

SwRI/JHUAPL/NASA