Pieces of a Disputed Past: Fossil finds enter row over humanity’s roots

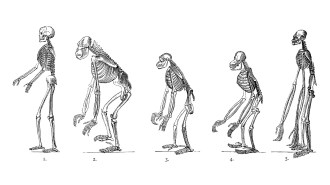

Two scientific teams have presented fossil discoveries with controversial evolutionary implications for two ancient species traditionally regarded as direct ancestors of Homo sapiens.

A 1.8-million-year-old upper jaw discovered in eastern Africa solidifies the position of Homo habilis as the oldest known member of the Homo genus, say anthropologist Robert J. Blumenschine of Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J., and his colleagues. Reported in the Feb. 21 Science, their analysis also challenges the widespread view that another species, Homo rudolfensis, lived in eastern Africa at the same time as H. habilis.

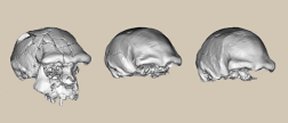

In the Feb. 28 Science, anthropologist Hisao Baba of the National Science Museum in Tokyo and his coworkers describe an undated Homo erectus cranium found in Java that fuels another prehistoric fray. According to the researchers, this specimen supports the contentious theory that H. erectus evolved in isolation in Indonesia and died out on Java about 35,000 years ago, after modern humans had settled on the island (SN: 12/14/96, p. 373).

Blumenschine’s team excavated the H. habilis jaw in Tanzania’s Olduvai Gorge. Fossil hunters had found the original H. habilis specimen, a lower jaw, in the same gorge nearly 40 years ago.

The newly discovered jaw was in sediment that also contained the bones of extinct gazelles and other animals, as well as simple stone tools. Some of the animal bones had incisions made by such tools, perhaps during the scavenging of carcasses by H. habilis members.

The estimated age of the H. habilis fossil hinged on analyses of argon isotopes in volcanic ash below the finds and evidence above the finds of a previously known and well-dated reversal in Earth’s magnetic field.

Blumenschine says the new fossil bears anatomical resemblances to both the original

H. habilis fossil and to a partial skull found in Kenya that’s usually classified as H. rudolfensis. “All three specimens are members of H. habilis,” he holds. However, several smaller-brained, smaller-toothed Olduvai fossils typically regarded as H. habilis represent a separate Homo species, Blumenschine and his colleagues conclude.

Bernard Wood of George Washington University in Washington, D.C., disagrees. In his view, larger and smaller Olduvai fossils actually represent, respectively, males and females of a species that wasn’t part of the Homo lineage. Wood classifies the Kenya skull fragment as a separate non-Homo species.

Another thorny debate swirls around H. erectus. According to Baba’s team, the latest fossil cranium of this species in Java, found by construction workers collecting sand by a river, exhibits an anatomy intermediate between a set of Javanese H. erectus fossils dated to at least 200,000 years ago and another set from at least 35,000 years ago. H. erectus on Java had little effect on the evolution of H. sapiens in that region, the scientists argue.

“Homo erectus probably did evolve on Java as a small, isolated population,” comments Philip Rightmire of the State University of New York at Binghamton.

Advocates of multiregional evolution reject that view. They say that H. erectus was just one variant of H. sapiens, which evolved in several parts of the world, including Indonesia.

Even amid such debates, “it’s nice to have this additional fossil evidence,” Wood says.

****************

If you have a comment on this article that you would like considered for publication in Science News, please send it to editors@sciencenews.org.