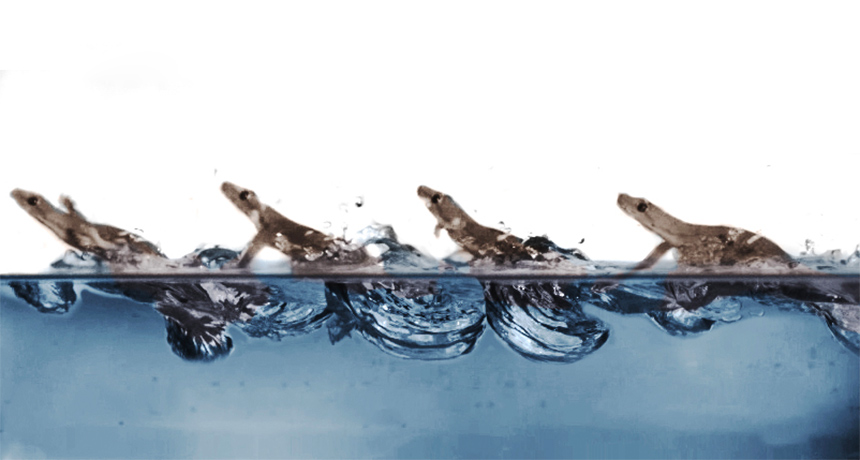

ON THE MOVE This composite image tracks the gait of a gecko as it crosses a tank of water, staying at the surface by slapping the water with its feet and getting some extra help from surface tension.

Pauline Jennings

- More than 2 years ago

Add water aerobics to the list of the agile gecko’s athletic accomplishments.

In addition to sticking to smooth walls and swinging from leaves, geckos can skitter along the surface of water. By slapping the water with all four limbs to create air bubbles and exploiting the surface tension of water, the reptiles can travel at speeds close to what they can achieve on land, according to a new analysis of high-speed video footage described December 6 in Current Biology.

In the world of water walkers, geckos occupy an awkward intermediate turf, says study coauthor Jasmine Nirody, a biophysicist at Rockefeller University in New York City and the University of Oxford. Small insects like water striders use surface tension, created by water molecules sticking together, to stay afloat. Bigger animals like basilisk lizards slap the surface of the water, creating air pockets around their feet that reduce drag and keep the lizards mostly above the water’s surface. But an animal needs to be fairly large to generate enough force to hold itself out of the water using that strategy.

“Geckos fall smack-dab in the middle” size-wise, Nirody says. “They shouldn’t really be able to do this at all.” And yet, when her colleague Ardian Jusufi of the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems in Stuttgart, Germany, was on a research trip in Singapore, he noticed small geckos skittering across the surface of puddles.

Back in the lab, the team filmed eight flat-tailed house geckos (Hemidactylus platyurus) crossing a tank of water, then slowed the footage to get a closer look at the action.

WATER WIZARDS To move quickly across water, geckos combine strategies used by tiny insects with strategies employed by bigger reptiles. |

All four limbs slap the water in a sort of inelegant, extra-splashy front crawl stroke, while the undulating tail adds forward propulsion, the researchers found. While geckos’ back legs remain submerged, the front 70 percent of their body is out of the water. Since water is harder to move through than air, that positioning helps the geckos travel through the water at about 10.5 body lengths, or up to nearly a meter, per second. It’s almost as fast as they move on land, and far faster than expected if swimming fully submerged.

“The thing that’s kind of spectacular about these animals is that they do look like they’re front crawling across the water,” says Tonia Hsieh, a biomechanics researcher at Temple University in Philadelphia who has studied the slapping behavior of basilisk lizards.

Despite paddling with four limbs instead of two like basilisk lizards, the geckos couldn’t generate nearly as much force. It’s enough to support only about 30 percent of their weight, Nirody calculated. And when she added dish soap to the water to lower surface tension, the geckos couldn’t move nearly as fast. That suggests that while surface tension alone can’t support geckos like it can a tiny insect, it still gives them an extra boost. Superhydrophobic skin that repels water helps too, further reducing drag.

Geckos may not truly walk on water in the way, say, that water striders do, Nirody admits. “They’re doing sort of a mixed-mode movement, combining techniques used in walking and swimming.” Someday, she hopes, the gecko’s hybrid approach might help researchers create robots that can travel more efficiently through water.

Editor’s note: This story was updated on December 7, 2018, to correct that Ardian Jusufi was on a research trip, not on a vacation, when he noticed geckos skittering across puddles.