Physics explains how pollen gets its stunning diversity of shapes

The varied patterns can all be explained by a process called phase separation

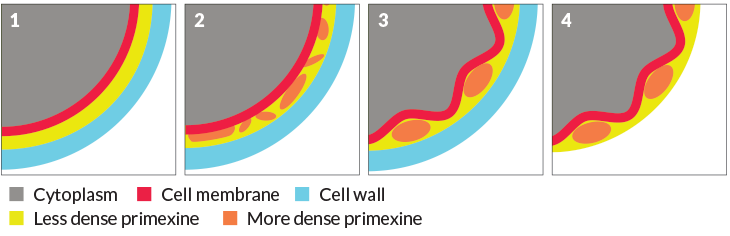

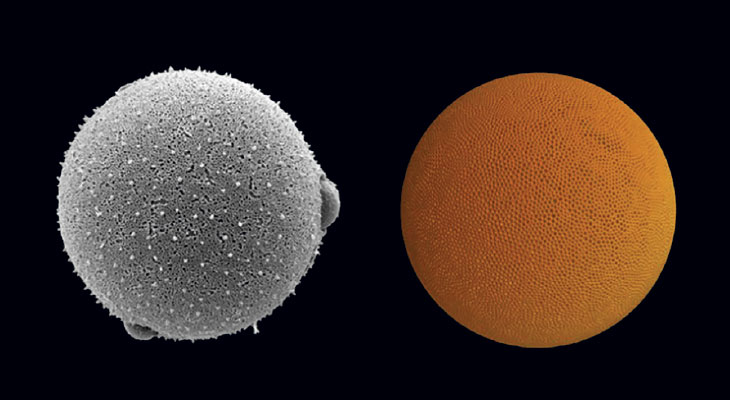

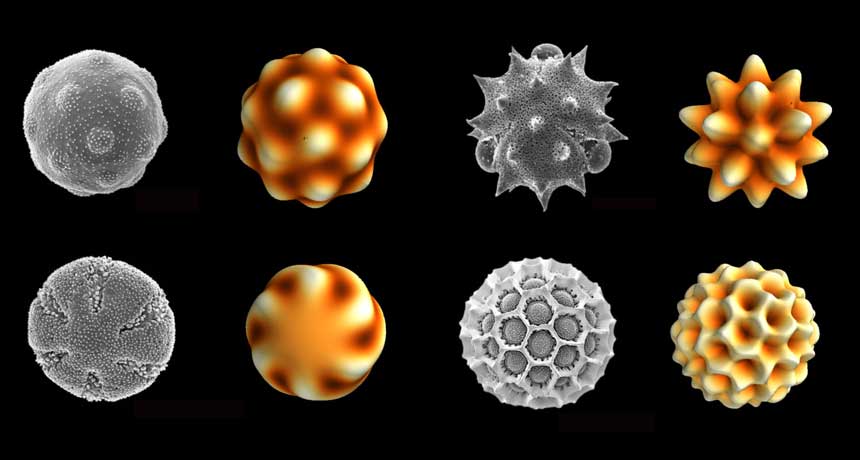

PATTERNS APLENTY Pollen from flowering plants comes in myriad shapes (as seen in these scanning electron microscope images, gray). Computer simulations based on a physics process called phase separation reproduced the grains’ shapes (orange).

SEM images: PalDat.org; Simulations: Asja Radja