From the November 27, 1937, issue

ATOM SMASHER

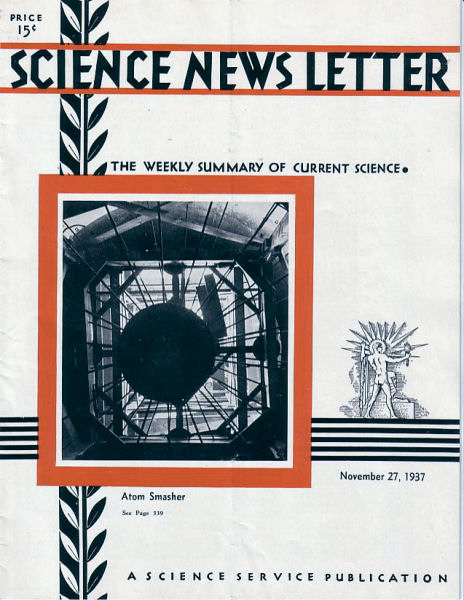

A new atom smasher is now being built by the Carnegie Institution of Washington, in the capital city. Seventy tons of steel are going into its 55-foot-high shell. The photograph on the cover of this week’s Science News Letter is of the inside framework looking directly upward toward the workmen at the top.

FIRST ESTIMATE OF SIZE OF NEW SUBATOMIC PARTICLE

The physicists’ unchristened baby, the subatomic particle discovered almost exactly a year ago, is between 100 and 160 times as massive as the electron.

This first estimate of the size of the most recent addition to the family of building blocks of the universe was reported (Physical Review, Nov. 1) by Drs. J.C. Street and E.C. Stevenson of Harvard University.

One thousand photographs of particle tracks produced by the bombardment of matter by cosmic rays were taken by the Harvard scientists in order to secure one photograph of the new particle, it is stated. The estimate of the size is based on the shape of the track the particle left behind it and on its penetrating power.

First reported by Science Service almost exactly a year ago, discovery of the particle, credited to Dr. Carl D. Anderson, California Institute of Technology Nobel Prize winner, and his associate, Dr. Seth Neddermeyer, occasioned a keen rivalry between the California scientists and their Harvard colleagues. The official announcement of its discovery by the Californians last spring was made almost simultaneously with a similar announcement from Harvard.

The particle is believed to carry the same negative electric charge as an electron, for the two Harvard scientists made that assumption in proceeding to analyze results of their lengthy experiments.

Four Geiger counters—devices for counting atomic discharges—were lined up in an ingenious experimental “telescope” layout in order to track the new particle. The first three counters were used to guarantee that particles were coming from only one direction outside the apparatus. The last counter served to cut off the observing chamber when high-energy particles, photographs of which were not wanted, passed through the counters. Had this last trap not been used 4,000 pictures—instead of 1,000—would have been necessary to obtain the one vital atomic portrait for which Drs. Street and Stevenson were looking.

PAST CLIMATIC CHANGES SHOWN BY POLLEN IN BOGS

Warming climate after the recession of the most recent glacial ice, a cooler period, and a more recent warming are shown by evidence collected by Drs. Harry V. Truman and Henry P. Hansen, students of ancient pollens, who have independently studied pollens found in the bogs of Wisconsin.

Dr. Truman, Beloit College ecologist, finds that during an early period in the existence of bogs in his area grasses and pine trees gave evidence of a cool dry period, probably immediately following the ice retreat. Later, a warmer period caused the displacement of trees by grasses, and still later, a cooler climate made conditions favorable for maple trees.

Dr. Hansen, University of Wyoming investigator, studying other bogs, finds evidence suggesting that boreal (cold climate) plant types declined shortly after the ice melted away, then a few of them returned after a period of many years. The findings of these two workers agree quite closely with those of other workers, who, using entirely different methods of approach, have also found evidence of similar postglacial climate changes.