BALTIMORE — A preliminary analysis of elderly stars in the Milky Way appears to strike a blow against the prevailing theory of galaxy formation. The study suggests that several large and seemingly disparate chunks of the Milky Way galaxy formed at the same time from the collapse of a single blob of gas and dust.

That’s in direct contrast to the leading galaxy-formation scenario, which holds that the Milky Way and other galaxies began small and grew bit by bit for the most part, gravitationally acquiring intergalactic gas and dust and merging with galaxies in their immediate neighborhood.

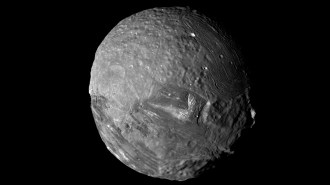

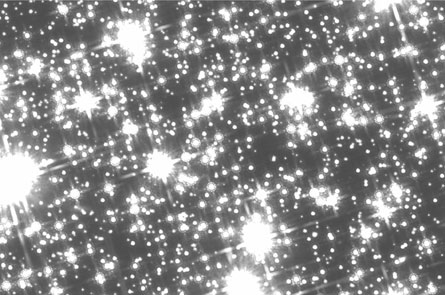

The new evidence, which astronomers emphasize is only tentative, comes from a new, ongoing study of a familiar globular cluster — a dense, elderly grouping of more than a million Milky Way stars collectively known as 47 Tucanae. Earlier this year, Harvey Richer of the University of British Columbia in Canada and his colleagues began examining 47 Tucanae with two Hubble Space Telescope cameras — the newly installed Wide Field Camera 3 and the Advanced Camera for Surveys, which stopped working early in 2007 but was revived by astronauts during the servicing mission last year.

The cluster lies near but not inside the Milky Way’s bulge, a massive concentration of stars that surrounds the galaxy’s core. But because the cluster shares several properties with the bulge, such as chemical composition and orbital motion, astronomers consider the age of 47 Tucanae a good proxy for that of the bulge.

An analysis of the Hubble portrait, which includes one of the deepest infrared views ever recorded, reveals that 47 Tucanae, and therefore the Milky Way’s bulge, formed between 11 billion and 12 billion years ago, Richer reported May 4 at a symposium on stellar evolution at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore. He said previous age estimates that did not use the new Hubble camera and put the cluster at a more youthful 9 billion years old are simply not correct.

“This is not a young cluster. That’s definitive,” Richer said. But he cautioned that both the analysis and observations of 47 Tucanae are ongoing, so the precise age determination is still “very preliminary.”

The new age determination places the bulge at roughly the same vintage as the halo of the Milky Way, a vast spherical region that extends to the outskirts of the galaxy and envelops the flattened disk containing the Milky Way’s signature spiral arms,.

Researchers had previously determined the halo’s age by studying several globular clusters that lie within it. The similarity in age of 47 Tucanae and the galactic halo suggests that the two structures may have formed simultaneously, in one giant monolithic gravitational collapse of material, Richer said. “It may have been that major components of the galaxy pretty much formed everywhere at the same time very early on and other bits and pieces came along later,” he noted.

A younger age for the bulge would have indicated that the galaxy grew more gradually and from the outside in, with the halo forming first and the central bulge arising a few billion years later.

But if the age estimate holds up, it would appear to be in conflict with the prescription for galaxy formation dictated by the cold dark matter theory, which holds that galaxies began as small fry that built themselves up by stealing gas and stars from their neighbors.

Evidence that the halo and the bulge of the Milky Way formed together could be seen either as a cosmic coincidence or a finding that suggests some previously unknown episode of violence early in the galaxy’s history, commented Rosie Wyse of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, who was not a collaborator on the study.

One possibility, she notes, is that the Milky Way suffered a major collision not long after its birth that drove material from the halo into the central part of the galaxy, forming the bulge. That could also explain why the mass of stars in the bulge is about 10 times heavier than that in the halo, she said.

The finding does not rule out the possibility that parts of the Milky Way grew by accreting, or gravitationally accumulating material, from neighbors, Richer said. Indeed, the Milky Way today continues to grow by pulling in small neighboring galaxies, such as the Sagittarius dwarf galaxy.