An ancient member of the human evolutionary family has put what’s left of a weird, gorillalike foot forward to show that upright walking evolved along different paths in East Africa.

A 3.4 million-year-old partial fossil foot unearthed in Ethiopia comes from a previously unknown hominid species that deftly climbed trees but walked clumsily, say anthropologist Yohannes Haile-Selassie of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History and his colleagues. Their report appears in the March 29 Nature.

To the scientists’ surprise, this creature lived at the same time and in the same region as Australopithecus afarensis, a hominid species best known for a partial skeleton dubbed Lucy. Another recent fossil discovery in Ethiopia suggests that Lucy’s kind walked much as people do today (SN: 7/17/10, p. 5).

“For the first time, we have evidence of another hominid lineage that lived at the same time as Lucy,” says anthropologist and study coauthor Bruce Latimer of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. “This new find has a grasping big toe and no arch, suggesting [the species] couldn’t walk great distances and spent a lot of time in the trees.”

Lucy’s flat-footed compatriot adds to limited evidence that some hominids retained feet designed for adept tree climbing several million years after the origin of an upright gait, writes Harvard University anthropologist Daniel Lieberman in a comment published in the same issue of Nature.

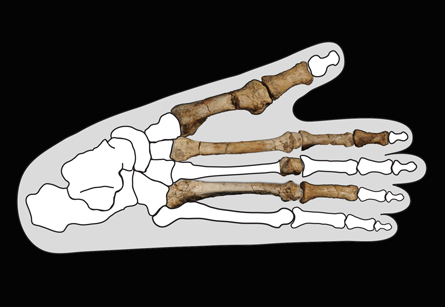

Armed with only eight toe bones, Haile-Selassie’s team doesn’t have enough skeletal evidence to assign a species name to the new find. But this mysterious hominid’s foot shares more in common with 4.4 million-year-old Ardipithecus ramidus, largely known from a partial skeleton nicknamed Ardi (SN: 1/16/10, p. 22), than with Lucy’s crowd.

Ardipithecus evolved into an initial Australopithecus species by 4.1 million years ago, paving the way for Lucy and her kin (SN: 4/15/06, p. 227). Haile-Selassie’s discovery may come from a hardy Ardipithecus lineage that managed to survive near A. afarensis for hundreds of thousands of years before dying out, comments anthropologist C. Owen Lovejoy of Kent State University in Ohio.

As in gorillas, Ardi and the newly discovered hominid possessed short, curving big toes capable of grasping against the second toe. Other toe bones from Ardi and the new discovery formed joints that enabled a two-legged stride.

The newly found fossils include an unusually long bone from the fourth toe that unexpectedly resembles corresponding toe bones of monkeys. No such fourth-toe bones have been found for Ardi’s and Lucy’s species.

An Ardipithecus species might have lived alongside A. afarensis in East Africa, but the evolutionary identity of the new foot fossils can’t be determined, remarks anthropologist Tim White of the University of California, Berkeley, who led excavations and analyses of Ardi’s remains.

“Haile-Selassie’s discovery highlights our lack of knowledge about hominid feet,” White says.