The debate over how long our brains keep making new nerve cells heats up

A new study finds no signs of newborn neurons in adults’ memory-making region

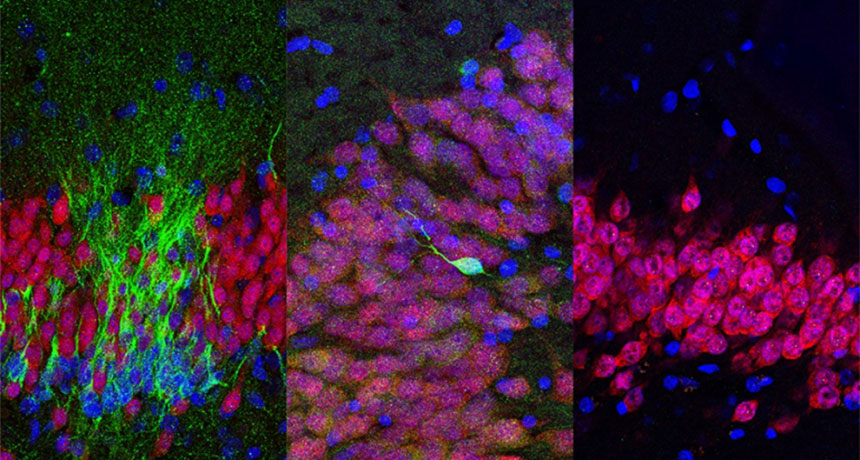

NO SIGNS In a study of human brains, young nerve cells (green) were visible in the memory-related hippocampus of a newborn (left), but were rare in a sample from a 13-year-old (center). None were seen in adult brains, including this sample from a 35-year-old (right).

ARTURO ALVAREZ-BUYLLA LAB