- More than 2 years ago

Researchers have made the first maps of corporate stock ownership for the stock markets of a large number of countries, 48 in all. The new network analysis technique reveals “backbones” in these ownership networks: big players that together own a controlling stake in more than 80 percent of the companies in the markets.

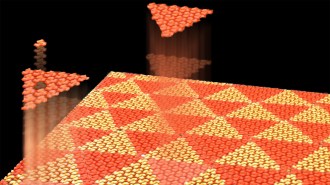

In these network diagrams, nodes represent either a company with publicly owned stock or a shareholder. Links between the nodes show which shareholders hold stock in which companies. Because many publicly owned companies also hold shares in other companies, many nodes have both “owner” and “ownee” links. Plotting all these connections creates a map of the ownership structure of a stock market.

Unlike the approach used in the new study, simpler network analyses can’t reveal these backbones of ownership because the market values of companies being traded aren’t taken into account. The new study, published online February 5 at arXiv.org, adds these market values. It also includes a way to account for indirect ownership, such as when a company owns stock in a second company that, in turn, owns stock in a third company.

“If you do a network analysis, you can see things that you couldn’t see otherwise,” says Stefano Battiston, coauthor of the study and a physicist at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich who studies complex socioeconomic networks. “Although from an individual point of view corporations are widely held, from a global point of view ownership is more highly concentrated.”

The resulting networks, which are based on a snapshot of market data from early 2007, show that concentration of ownership in these markets varies from country to country. The United States and United Kingdom had the highest concentration of ownership, while ownership was less concentrated in European and Asian countries. Some companies held so much stock at the time that they constituted part of the backbones of many countries. The top ten such companies were:

1. The Capital Group Companies (U.S.)

2. Fidelity Management & Research (U.S.)

3. Barclays PLC (U.K.)

4. Franklin Resources (U.S.)

5. AXA (France)

6. JPMorgan Chase & Co. (U.S.)

7. Dimensional Fund Advisors (U.S.)

8. Merrill Lynch & Co. (U.S.)

9. Wellington Management Company (U.S.)

10. UBS (Switzerland)

“The results nicely show how structure emerges from an otherwise weak signal, revealing the ownership backbone within and across countries,” comments Bruce Kogut, an economist at the Columbia Business School in New York.

Most of these companies manage mutual funds, so they hold large portfolios of a wide variety of stocks on behalf of their clients. It’s not surprising then that they would top the list, but the new study confirms this intuition with hard data.

“It’s interesting that you can get these results that, if you asked an experienced economist they’d probably have a gut feeling about, but now you can show it in a quantitative way,” comments Jörg Reichardt, a physicist at the University of Wuerzburg in Germany. “They’ve done a great job of making it mathematically rigorous.”

The implications of these backbones of concentrated ownership for the current global economic crisis are unclear, Battiston says. He and his colleagues are now analyzing stock market data from after the economic downturn for comparison and working on theories for how the structure of ownership affects the overall stability of the market.

“In contrast to the mainstream economic view that a more interconnected market is always more stable, in many cases it can actually be more unstable because there are some mechanisms that have not been accounted for in the economic theory so far,” Battiston says. “If there are amplification systems and feedback, then a more connected world is more unstable.”