NASA’s Parker probe has spotted the Geminid meteor showers’ source

Data from space could help pinpoint the origins of one of Earth’s most famous falling stars

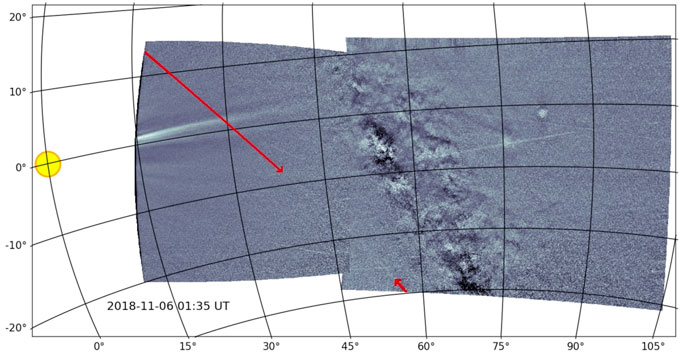

The Parker Solar Probe has glimpsed the stream of debris that feeds the Geminid meteor shower (pictured in this composite image) out in space for the first time. For earthbound viewing, the showers are scheduled to peak overnight December 13 to December 14.

Genevieve de Messieres/shutterstock