Monkeys reached Americas about 36 million years ago

Peruvian fossils suggest ancient African primates somehow crossed the ocean

OLD TIES Roughly 36-million-year-old primates from Peru and Libya (rough reconstructions shown) display similarities that, like fossils of these creatures, denote a spread of ancient primates from Africa to South America. Red dots show fossil sites.

Ron Blakey

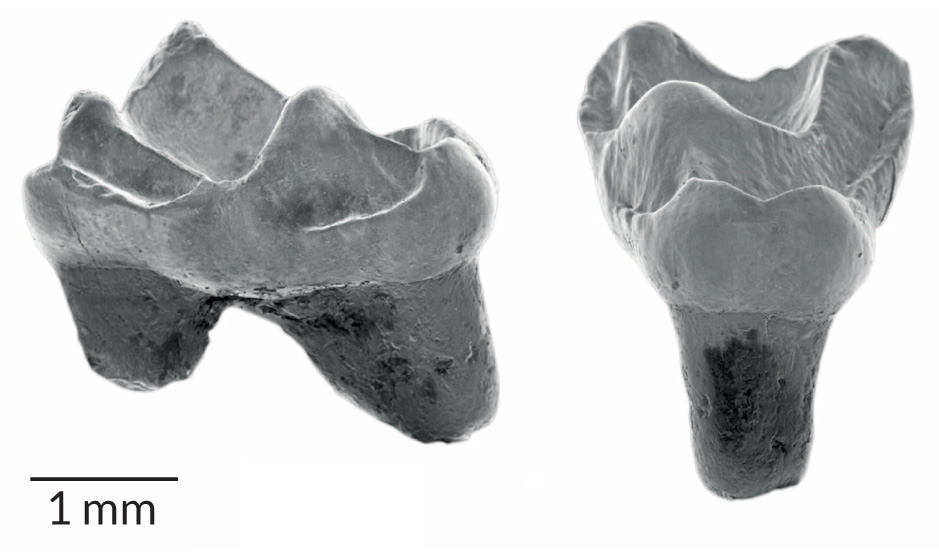

A handful of roughly 36-million-year-old fossil teeth unearthed in Peru have put new bite into the idea that ancient African monkeylike primates somehow reached South America and sparked the evolution of New World monkeys. Although scientists previously suspected that African animals got the primate ball rolling in the Americas, the Peruvian finds provide the first fossil backup for the scenario.

Two complete and two partial molar teeth excavated on a riverbank in Peru’s Amazon region represent the oldest known New World primates, says a team led by paleontologist Mariano Bond of the La Plata Museum in Argentina. The finds, from a species the authors dub Perupithecus ucayaliensis, closely resemble previously reported teeth of North African primates that lived between 39 million and 35 million years ago, the investigators report online February 4 in Nature.

Teeth of living and extinct South American monkeys — including those of a 26-million-year-old Bolivian primate that was until now the oldest known New World primate — differ in many ways from the newly discovered teeth, the researchers say. In other words, Perupithecus looks like a relatively recent arrival to South America that retained teeth resembling those of African monkeylike creatures.

An evolutionary connection between North African and Peruvian primates could have arisen in one of two ways, the researchers propose. Perupithecus might have originated in Africa and, after reaching South America, evolved into a New World monkey. Or Perupithecus may have possessed signature traits of New World monkeys, such as a broad, flat nose and a long tail, before leaving Africa.

In either case, at least one intrepid band of ancient African primates may have crossed the Atlantic Ocean, possibly after getting trapped on large rafts of floating vegetation. Masses of floating vegetation can appear when massive storms or tsunamis hit coastal areas.

“Crossing the Atlantic Ocean by any means other than a vegetation raft would appear to be most unlikely,” says paleontologist and study coauthor Kenneth Campbell Jr. of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

Campbell has explored the Amazon for several decades in search of fossil birds. Discovering the new primate fossils was a fortunate accident, he says.

For now, dating of Perupithecus relies on comparisons with primate fossils of known age found elsewhere in South America and the age of the geologic formation from which the fossils were excavated. Further research will attempt to secure a more accurate age estimate.

“These new finds are a first,” remarks biological anthropologist Daniel Gebo of Northern Illinois University in DeKalb. “We have struggled for years to find older and more primitive primate fossils in South America.”

Perupithecus fossils demonstrate that monkeys were already in South America around the time when geneticists and paleontologists have predicted that New World monkeys branched off from African monkey ancestors, says paleontologist Erik Seiffert of Stony Brook University in New York. “Perupithecus was presumably very close to the line of descent” that ultimately produced living New World monkeys, Seiffert suggests.