X-rays reveal what ancient animal mummies keep under wraps

A new method of 3-D scanning mummified animals reveals species IDs and causes of death

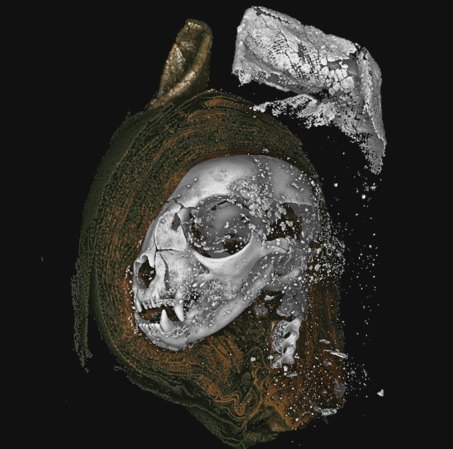

Three-dimensional scans of three animal mummies from Swansea University’s Museum of Egyptian Antiquities (a snake (left), bird (top right) and cat (bottom right)) have revealed the mummies’ identities and other secrets. The mummies have not been radio carbon dated, but are likely at least 2,000 years old.

Swansea University