FISH HAUL A fisherman sorts through Atlantic cod and little skate caught in Stellwagen Bank in the Gulf of Maine. Warming waters and fishing can affect bioaccumulation of toxic methylmercury in these fish, a study suggests.

Jeff Rotman/Science Source

Climate change and overfishing may be hampering efforts to reduce toxic mercury accumulations in the fish and shellfish that end up on our plates. Mercury emissions are decreasing around the globe. But new research suggests that warmer ocean waters and fishing’s effects on ecosystems can alter how much mercury builds up in seafood.

Fishing practices increased methylmercury levels in the tissue of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) caught in the Gulf of Maine by as much as 23 percent over a roughly 30-year period, researchers estimate. That’s despite decreases in atmospheric mercury levels over the same time period, from the 1970s to the 2000s. The finding is based on simulations of mercury emissions as well as ecosystem changes related to fishing. It reveals how the diet of cod, driven by the rebound of once-overfished herring, plays an important role in determining how much mercury accumulates in the fish, the team reports online August 7 in Nature.

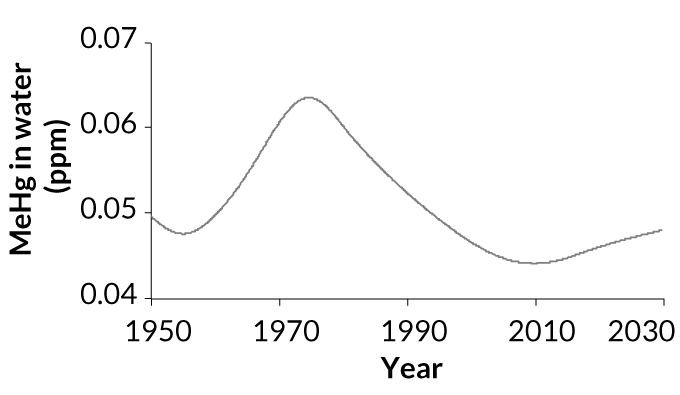

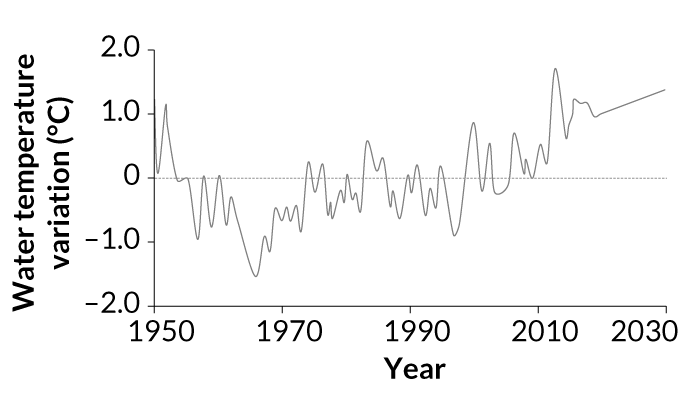

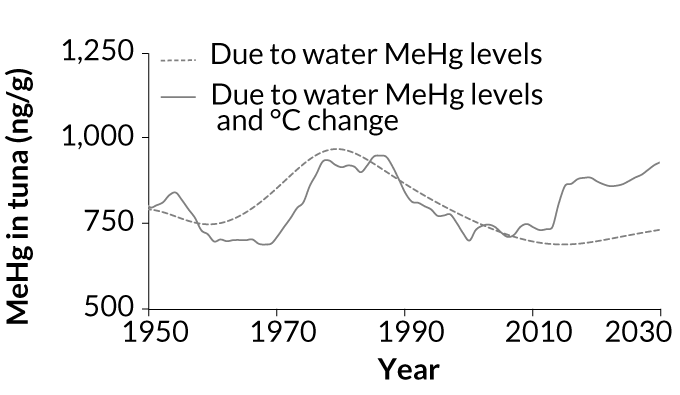

The scientists also created simulations of the effects of warming seawater on mercury bioaccumulation, incorporating changing emissions and temperatures as well as mercury accumulations measured in Gulf of Maine Atlantic bluefin tuna since 1969. Those simulations suggest that seawater temperature increases could be responsible for as much as a 56 percent increase in methylmercury concentrations found in Gulf of Maine Atlantic bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus), the team found.

“This is really the first investigation to look at migratory marine fish and the potential impacts of temperature and overfishing” at the same time, says study coauthor Elsie Sunderland, an environmental chemist at Harvard University. Scientists have long assumed that when it comes to mercury piling up in seafood, the only factor that matters is how much is being sent into the sky, she says.

Emissions do matter, but are only one piece of the puzzle. Mercury emissions, as inorganic mercury, can come from both human activities such as burning coal or natural sources like volcanoes. Eventually, that mercury rains back down onto Earth’s surface. Microorganisms then convert the mercury into an organic form called methylmercury that can cling to organic matter. When tiny creatures consume that matter, the metal gets stored in their fatty tissues. And so on up the food chain: As increasingly larger animals eat methylmercury-laden dinners, more and more of the metal accumulates in the predators.

In oceans, this toxic trek can go from zooplankton to small fish and crustaceans, then bigger fish and, finally, people. That accumulation can be deadly: Methylmercury poisoning can damage the central nervous and digestive systems, causing cognitive damage, kidney failure and death.

The good news is that emissions are no longer on the rise. From 1990 to 2010, mercury emissions from human activities decreased from 2,890 megagrams per year to 2,280 megagrams per year. Emissions, particularly from the European Union and the United States, continue to decline, according to a global assessment by the United Nations Environment Programme. A 2017 global treaty to reduce emissions could lower those numbers further.

In the United States, mercury emissions from coal-fired power plants dropped from about 41,700 kilograms in 2006 to about 6,300 kilograms in 2016, a decrease of 85 percent. That decrease is the direct result of state regulations on emissions and, later, a 2011 federal standard, Sunderland says.

But, surprisingly, that hasn’t led to a straightforward decrease in the mercury measured in fish. Some fish in the Gulf of Maine, such as Atlantic cod, showed increases in mercury in their tissues over time, the team found. Others, including the spiny dogfish (Squalus acanthias), showed decreases.

To try to solve that mystery, biogeochemist Amina Schartup of Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, Calif., and colleagues zoomed in more closely on the Gulf of Maine ecosystem. The area has a long history of intense scrutiny, both as a historical fishing ground as a hot spot for global warming. Seawater temperatures there are among the fastest rising in the world.

The team looked at methylmercury levels in seawater, sediments and across the ecosystem. The researchers also wanted to compare these data with changes in the diets of Atlantic cod and spiny dogfish through time. To do this, the team analyzed the stomach contents of the two species from the 1970s and 2000s, using the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s extensive records on fish stocks in the region.

Mercury differences between the two types of fish were directly related to diet changes resulting from humans’ fishing habits, the researchers found. Cod and dogfish both prefer to eat herring, but in the 1970s, herring populations in the region collapsed due to overfishing. So the cod turned to smaller herring, which have relatively lower mercury levels, and the dogfish turned to heavily mercury-laden squid. But then herring came back on the menu as its populations rebounded after the 1970s. Dogfish ate fewer squid, and their mercury increases slowed. Cod, on the other hand, saw a more dramatic increase in mercury accumulation.

Seawater temperatures in the Gulf of Maine may also alter mercury accumulation. Using calculations of energy expenditure, growth and prey consumption for Atlantic bluefin tuna, the researchers estimated how much warming waters increase fish activity. More active fish consume more food and accumulate more mercury, which could explain higher than expected mercury levels measured in the fish given declining emissions, the scientists suggest.

Next, the team plans to expand these simulations beyond the Gulf of Maine, Sunderland says. “That’s really the goal,” she says. “To understand the changing impacts for all these ecosystems.”

William Cheung, a marine ecologist at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, says another step will be to link these findings to public health, and to make projections for future seafood safety. “It’s a really important piece of work,” he says. “Historically, we’ve only looked at these problems individually: climate change, overfishing, contamination…. We may be underestimating the level of risk and impacts.”

But efforts to project those risks going forward is a task made trickier by some uncertainty in future mercury emissions, particularly from the United States. In December 2018, the Environmental Protection Agency proposed weakening its mercury regulations, suggesting that they are no longer “appropriate or necessary.”

Yet those regulations “are a tremendous environmental success story,” Sunderland says. Rolling those regulations back could undo a lot of the good that they have done, she says. “The situation would be much worse without them.”