Medications alone work as well as surgery for some heart disease patients

Patients with stable ischemic heart disease can avoid stents or bypass surgery

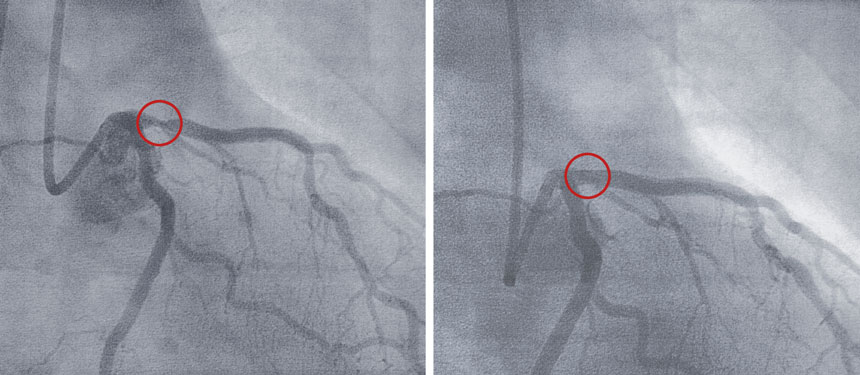

A doctor views an image of the heart during a coronary angioplasty, during which a tube is inserted into the vessels to clear a blocked artery and possibly place a stent. Some patients with heart disease could avoid this procedure and treat their condition with medical therapy alone, researchers say.

U.Ozel.Images/E+/Getty Images Plus

- More than 2 years ago

In their heyday, stents and bypass surgery were the go-to treatment for patients newly diagnosed with heart disease. That began to change about a decade ago, after new data emerged suggesting these procedures were no better than treatment with medical therapy alone for patients whose heart-related symptoms aren’t considered an emergency. Now a large study has tipped the scales further, reporting that statins, aspirin and other medications together protect these patients just as well as stents or bypass surgery against heart attacks and death.

The key to managing these patients, who have stable ischemic heart disease, “is medicines, medicines, medicines,” says Michael Gavin, a cardiologist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston who was not involved in the study. “That’s what’s going to stop you from having a heart attack.”

Going the medical therapy route does require that patients are committed to that route. That means seeing the doctor regularly, keeping up with medications and exercise and eating a healthy diet. Medical therapy “gives a good prognosis,” says preventive cardiologist Gina Lundberg of Emory University School of Medicine, who was not involved in the study. But “you can’t say ‘I don’t want the stent,’ and then not do all those things, and get a good result.”

The federally-funded study, called ISCHEMIA, is the largest clinical trial to examine whether medical therapy alone, or along with stents or bypass surgery, reduces death or heart attacks in patients who have heart disease primarily due to plaque-containing, narrowed coronary arteries, but who have manageable pain or other symptoms. The participants in the invasive procedure group had a device threaded through the arteries, followed by placement of a stent to keep an artery open or else bypass surgery to divert blood flow around a blockage. The procedures come with risks such as bleeding or the formation of blood clots that can block an artery again.

The study measured how well patients did in terms of heart attacks, hospitalization for worsening heart health or death. Medical therapy alone produced very similar results to invasive procedures plus medical therapy in terms of rates of death and the chance of a heart attack. The results, unveiled at the Nov. 16 American Heart Association scientific sessions, reinforce the findings of two other trials from about decade ago, but extend them to patients with stable symptoms but with moderate to extensive coronary disease.

When it came to quality of life, patients who had an invasive procedure plus medication reported more improvements in their symptoms in the first year following the procedure than those on medical therapy alone. It was most pronounced for someone with daily or weekly chest pain: While 20 percent on medical therapy alone were pain free after a year, that was true for 50 percent who’d had an invasive procedure plus medical therapy, says Judith Hochman, a cardiologist at the New York University Grossman School of Medicine and one of the lead researchers of the ISCHEMIA trial.

“What patients care about really is, ‘Is this treatment going to make me live longer or feel better? Preferably both,’” Hochman says. For the invasive treatment, “we didn’t see that it would prolong life over the time period we studied, about five years.” But for those who had chest pain, called angina, at the start of the study, the invasive strategy plus medications was superior, she says.

That makes sense, says Gavin, because there tends to be a connection between the pain and the blockage in an artery. “If you fix that blockage, symptoms more than likely will get better,” he says. But “the area that’s going to cause the heart attack is just as likely to be hiding out somewhere else within your coronary arteries as it is to occur where the stent is … the medicines are what’s going to treat everything.”

Heart disease is the leading cause of death in the United States; coronary artery disease is the most common type. The study included close to 5,200 participants in 37 countries with moderate to extensive coronary artery disease. That could mean patients had narrowing or blockages in any or even all of the three major arteries that supply blood to the heart. But their condition is considered stable because these patients have pain when the heart has to work harder, such as when they exert themselves, but not while at rest.

The study’s results do not apply to people who have chest pain at rest or while sleeping or chest pain that arises suddenly or with very little exertion. These patients have what’s called unstable ischemic heart disease, and it puts them in immediate danger of a heart attack. In these cases, doctors will place a stent or proceed with bypass surgery as well as prescribe medical therapy.

Women made up only 23 percent of the participants, which means “we definitely have to put an asterisk by the information as it applies to women,” says Lundberg, who is the clinical director of the Emory Women’s Heart Center. Still, that adds up to more than 1,100 women studied, she says, “so I wouldn’t say the study doesn’t count; it just might not be the final answer.”

Heart disease can look different in men and women. Plaques in the arteries, which are made of cholesterol, cells and other substances, tend to rupture in men, causing a blockage at the site that can lead to a heart attack. But in women, plaques can behave in a few different ways that contribute to heart attacks, including the erosion of plaques, in which small pieces break off and flow away, producing clots further down the vessel. Plus, women are more likely than men to have heart disease that doesn’t arise from a blockage at all, but from a condition in which the small blood vessels that feed the heart don’t function properly, called microvascular dysfunction.

Treatment for stable heart disease patients has been moving towards the medical therapy approach in the United States. The new work will continue the push in that direction, Gavin says. “It’s a nice trial to have when talking to patients in terms of reassuring them” about pursuing medical therapy alone.