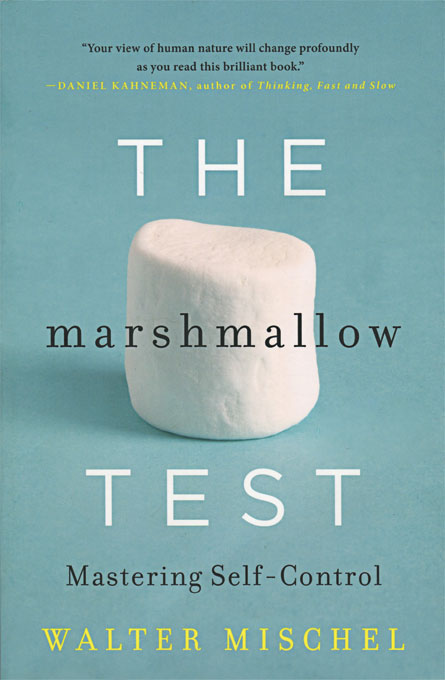

Mastering the art of self-control

Psychologist Walter Mischel discusses the science behind willpower

SWEET REWARDS In a study, kids who waited for two marshmallows, instead of one right away, grew up to do better in school, get better jobs, maintain better physical health and feel better about themselves than their grab-and-go peers.

John Morgan/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0)

Columbia University psychologist Walter Mischel made his scientific mark by tempting children with marshmallows. For nearly 50 years, Mischel has studied whether kids would eat, say, one marshmallow right away or wait 20 minutes to receive two marshmallows. Kids who waited for double the goodies grew up to do better in school, get better jobs, maintain better physical health and feel better about themselves than their grab-and-go peers (SN: 10/8/11, p. 12). Science News talked to Mischel about his new book, The Marshmallow Test, which describes how self-control can be learned and applied to challenges ranging from losing weight to planning for retirement.

Columbia University psychologist Walter Mischel made his scientific mark by tempting children with marshmallows. For nearly 50 years, Mischel has studied whether kids would eat, say, one marshmallow right away or wait 20 minutes to receive two marshmallows. Kids who waited for double the goodies grew up to do better in school, get better jobs, maintain better physical health and feel better about themselves than their grab-and-go peers (SN: 10/8/11, p. 12). Science News talked to Mischel about his new book, The Marshmallow Test, which describes how self-control can be learned and applied to challenges ranging from losing weight to planning for retirement.

What is the most important lesson of research on self-control?

No matter how bad you are at resisting temptations, there are ways to enhance self-control if you’re motivated to use them. Research has shown that self-control involves a set of cognitive skills that are quite teachable, especially early in life. Successful delayers in the marshmallow test use these cognitive skills to think up games and other strategies that help them to cool impulsive urges and reach future goals. We don’t have to be victims of our biology, genes or circumstances. People can learn self-control strategies and become active agents in determining how their lives play out.

Willpower is sometimes described as a limited mental resource that can easily be drained, at least temporarily. Do you agree?

I agree that a person’s potential for self-control becomes limited as stress levels and fatigue go up. But there are huge differences across individuals in what can be accomplished when stressed and tired. Exhausted people can expend huge amounts of energy if they have strategies they are motivated to use in order to reach a burning goal.

How can people who have lost control of some part of their lives turn things around?

In my book, I use myself as an example of how to reverse destructive behavior. I’m 84 years old, and 50 years ago I was addicted to cigarettes. I also smoked pipes and cigars. I realized I had a problem when I was standing in the shower and noticed a lit pipe in my hand. Shortly after that I saw a hospital patient on a gurney with green X marks on his chest and head. A nurse told me the man had spreading cancer and the marks showed where he was going to receive radiation treatment. I visualized myself as a cancer patient and decided to overcome the conditioned, emotional responses that made me want to smoke. Whenever I felt the urge to light up, I inhaled from a can filled with stale cigarette butts and pipe debris. That’s a nauseating smell. I also made a deal with my 3-year-old daughter to stop sucking my pipe if she stopped sucking her thumb. And I publicly promised coworkers and students that I wouldn’t mooch cigarettes from them. After a few tough weeks, it worked.

Is it time for a renewed scientific focus on free will?

We need a renewed scientific focus on the nature of human nature. What’s become clear in the past 20 years is that the plasticity of brain and behavior is far greater than had been assumed. Researchers need to examine psychological and environmental conditions that enable dramatic behavior changes.