Lizard spit can help detect a rare pancreatic tumor

Elusive insulinomas can cause dangerous dips in blood sugar

A protein found in the saliva of Gila monsters (one shown) can bind to certain cells in the pancreas, making it a potentially useful tracer for scans for a rare, benign type of pancreatic tumor.

Michael D. Kern/Nature Picture Library

A molecule in lizard saliva may make it easier to find certain tumors in the pancreas.

Insulinomas — benign tumors that can cause low blood sugar and sudden fainting spells — are notoriously hard to detect using current scanning methods. But by using a tweaked variant of a protein found in Gila monster saliva as a radioactive tracer, a new type of PET scan found the tumors in 95 percent of confirmed cases, researchers report in the October Journal of Nuclear Medicine. PET scans used now to detect such tumors had just a 65 percent success rate, the team found.

One of the main functions of the pancreas is to produce insulin, a hormone that keeps blood sugar levels in check (SN: 10/22/24). The task of making that insulin falls to specialized cells called beta cells. But sometimes these cells malfunction and form insulinomas. These tumors are rare, affecting just 1 to 4 people out of a million per year globally, but debilitating to those who have them.

“Many of [these tumors] are benign, very small and very efficient factories of insulin. They can cause you to have low blood sugar, which might even make you pass out or have a seizure,” says Peter Choyke, a radiologist at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Md. “Even when they’re very small, it’s very urgent to get to the diagnosis quickly and accurately, so that a surgeon can go in knowing exactly where the tumor is and remove just that.”

If doctors manage to find the tumors, surgically removing them cures the patients and lets them live a normal life. But finding the insulinomas is hard. Current methods of locating them include CT and MRI scans as well as PET scans that are used to find malignant pancreatic tumors, but can’t always detect the much smaller insulinomas. In a PET scan, doctors inject radioactive molecules into patients. The molecules build up at specific locations in the body, like in cancers, so analysis of their radiation can give doctors a three-dimensional view of cancerous cells (SN: 4/18/22).

“If [they] didn’t know where [the tumor] is, surgeons used to slice the pancreas until they found it,” says Martin Gotthardt, a nuclear medicine researcher at Radboud University Medical Center in Nijmegen, Netherlands. “In case an insulinoma cannot be detected nowadays, [the patients] are not operated on, because [doctors] don’t want to remove the whole pancreas.”

Enter the Gila monster (Heloderma suspectum), a lizard found in the deserts of the U.S. Southwest. One protein found in its saliva, named exendin-4, is made in the lab and used to treat diabetes (SN: 8/12/03). It can bind to and activate pancreatic receptors called GLP1Rs, triggering them to produce more insulin. Shortly after its success with diabetes treatment, Gotthardt and other scientists realized in the mid-2000s that insulinomas, typically a clump of many beta cells, also contain a high amount of GLP1Rs, making exendin-4 an attractive candidate to help localize these pesky tumors.

Early studies showed that exendin-4 with a radioactive molecule attached could be used in PET scans to detect insulinomas in people, but injecting high amounts caused some side effects, such as nausea, headaches and even lower blood sugar. In the current study, Gotthardt and his team added another molecule to help further stabilize the radioactive exendin-4. This ensured that even low amounts of the modified exendin-4 showed high radioactivity; doctors could inject less of it into the patients, thus leading to fewer adverse effects.

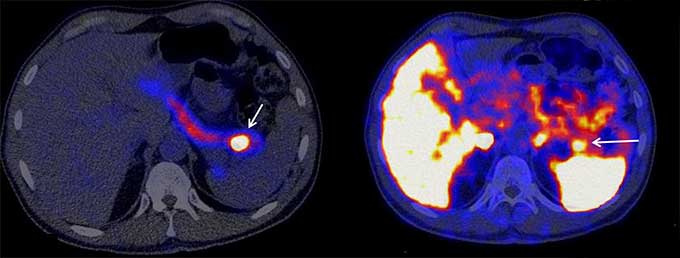

To test their new tracer, the researchers recruited 69 people who had been biochemically diagnosed as having low blood sugar due to excessive insulin. Each underwent all standard imaging tests as well as the new exendin-4 PET scan, which led to 53 individuals undergoing surgery to remove suspected tumors. Out of those 53 confirmed cases, the tumor showed up in 50 of the exendin-4 PET scans, as opposed to just 35 of the standard PET scans. In seven cases, the exendin-4 scans detected insulinomas while standard PET, CT and MRI imaging picked up nothing.

The exendin-4 was also very good at picking up only the insulinomas in the scan, with less background noise compared with currently used PET scans, and had fewer side effects on the patients compared to previous versions of the exendin-4 radiotracer.

“I think [this] work is very valuable in showing how exendin-4 could be used in the diagnosis of insulinoma and maybe replace a lot of the imaging techniques that are currently used that aren’t as good,” Choyke says.

Gotthardt and his team are now focused on helping other labs and hospitals set up this technique. “We just want to spread the technology,” he says. “Everybody should be able to use it, because it really helps the patients.”