Interstellar comet Borisov has an unexpected amount of carbon monoxide

Second visitor from the stars has three times the CO relative to H2O than any local comets

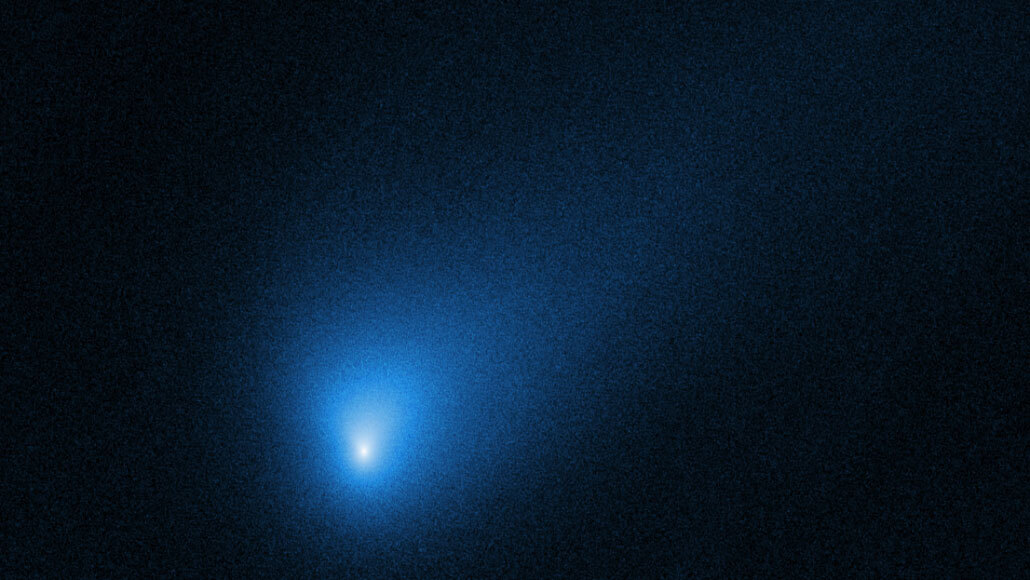

A wispy tail of gas and dust trails behind interstellar comet 2I/Borisov, seen about 420 million kilometers from Earth in this Hubble Space Telescope picture from October 12, 2019.

D. Jewitt/UCLA, ESA, NASA