Inked mice hint at how tattoos persist in people

Immune cells pass pigment from one generation to the next

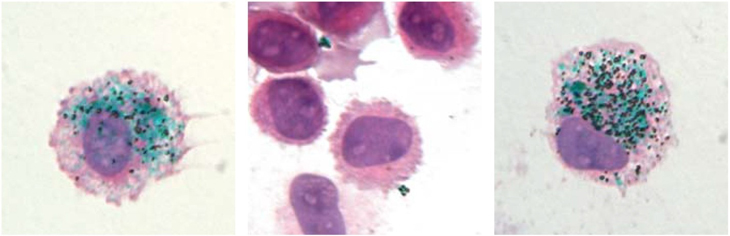

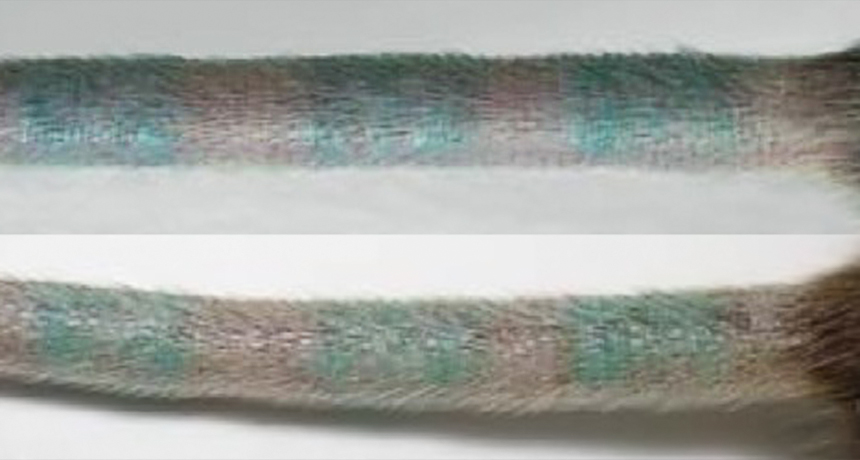

TAIL TATS When researchers tattooed mouse tails, the only cells found with ink inside were macrophages. The tattoo appeared the same before (left) and after (right) ink-holding macrophages were killed, because it was recaptured by new macrophages.

A. Baranska et al/J. Expt. Med. 2018