‘Slam-dunk’ find puts hunter-gatherers in Florida 14,500 years ago

Dating of stone tools adds to evidence for pre-Clovis inhabitants in North America

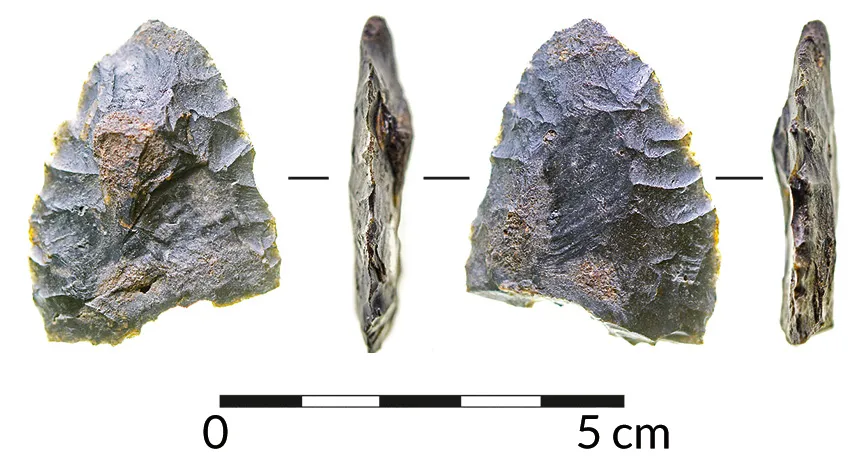

FLORIDA FIRST Excavation of a submerged site in Florida produced evidence, including this stone artifact shown from different angles, that people lived there 14,550 years ago.

CSFA

Big game hunters of the Clovis culture may have just gotten the final blow to their reputation as North America’s earliest settlers. At least 1,000 years before Clovis people roamed the Great Plains, a group of hunter-gatherers either butchered a mastodon or scavenged its carcass on Florida’s Gulf Coast.

Stone tools discovered in an underwater sinkhole in the Aucilla River show that people were present at the once-dry Page-Ladson site about 14,550 years ago, reports a team led by geoarchaeologists Jessi Halligan of Florida State University in Tallahassee and Michael Waters of Texas A&M University in College Station. The Clovis people appeared in North America around 13,000 years ago.

Radiocarbon dating of twigs, seeds and plant fragments from submerged sediment layers provides a solid age estimate for six stone artifacts excavated by scuba divers, the team reports May 13 in Science Advances. Five of those finds consist of thin pieces of stone hammered off chunks of rock. Divers also recovered part of a stone cutting instrument.

This research shows that the Page-Ladson site “is one of the best cases for pre-Clovis archaeology in the Americas,” says geoarchaeologist Vance Holliday of the University of Arizona in Tucson.

A human presence so early in North America’s southeastern corner aligns with growing evidence that people reached a land bridge connecting northeastern Asia to what’s now Alaska around 23,000 years ago (SN: 8/22/15, p. 6) before entering the Americas perhaps 18,000 to 16,000 years ago.

From 15,000 to 14,000 years ago, humans explored and settled many parts of the Americas. Evidence of hunter-gatherers from that time includes sites in Oregon (SN: 8/11/12, p. 15), Texas (SN: 4/23/11, p. 12) and Chile (SN: 12/26/15, p. 10). Those discoveries have chipped away at the popular view that the Clovis people were the New World’s first inhabitants. But some researchers have questioned whether these sites are as old as reported.

Previous pre-Clovis finds at Page-Ladson have come under fire, too. Underwater investigations of the Florida site from 1983 to 1997 yielded eight stone artifacts and a mastodon tusk displaying parallel grooves possibly made by people wielding stone implements. An initial radiocarbon date of about 14,400 years for these finds, as well as a proposal that people had butchered the mastodon, drew challenges from several researchers.

New radiocarbon dates and stone tool discoveries identify Page-Ladson as a “slam-dunk pre-Clovis site,” Waters says.

In addition, a reexamination of grooves on the mastodon tusk — conducted by paleontologist and study coauthor Daniel Fisher of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor — concludes that tool users probably made those marks while removing the tusk from the animal’s skull. Fisher suspects Page-Ladson people sought edible tissue at the tusk’s base and in its inner cavity, as well as ivory for weapons.

Florida’s pre-Clovis people probably had plenty of opportunity to hunt or scavenge the remains of such creatures. High concentrations of Sporormiella spores, a dung fungus peculiar to plant-eating animals, turned up in several submerged sediment layers. That evidence indirectly points to mastodons and other now-extinct animals inhabiting Florida’s Gulf Coast at the same time as pre-Clovis humans. No signs of Sporormiella appear in sediment dated at about 12,600 years old, roughly the time when researchers suspect many large North American animals died out.

That doesn’t necessarily mean that people abandoned the Page-Ladson area at that point. Pre-Clovis groups ate whatever was available, however they could get it, from mastodons to shellfish, says archaeologist James Adovasio of Florida Atlantic University Harbor Branch in Fort Pierce. Ancient Americans adapted to one habitat after another as they moved relatively quickly through North and South America, he says.

It’s too early to say whether pre-Clovis folk in Florida died out or were ancestors of later Clovis people, Adovasio says.