What happens when governments crack down on scientists just doing their jobs?

Human rights take a back seat when state leaders try to control the narrative

Scientists can run into trouble when research results clash with government desires.

iStock/Getty Images Plus, adapted by E. Otwell

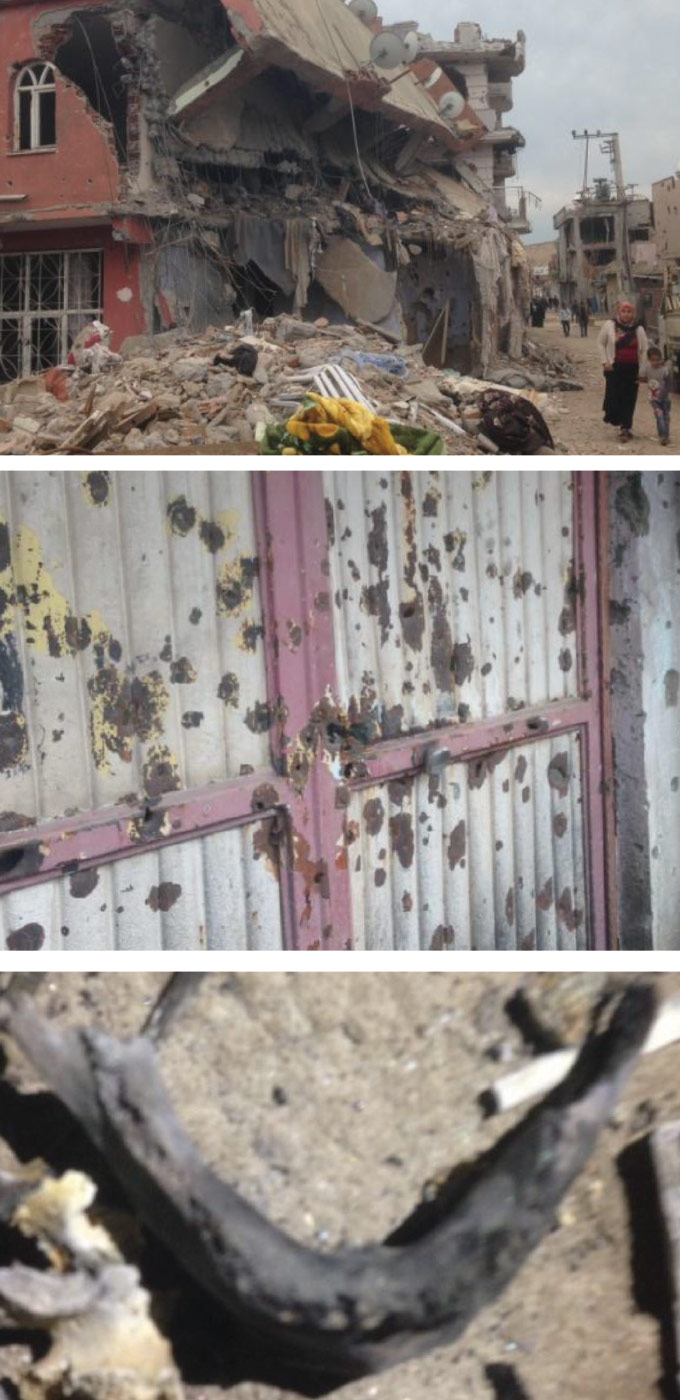

On a sunny day in March 2016, Turkish forensic physician Şebnem Korur Fincanci drove into Cizre, a town in southeastern Turkey. The government had just lifted a 79-day curfew meant to help the Turkish military rout out members of the separatist PKK, or Kurdistan Workers’ Party. Turkey has long fought to keep insurgents from creating a separate Kurdish country, and has designated the PKK as a terrorist organization.

Like most people outside of Cizre, Fincanci had no idea what had transpired during the lockdown. She arrived to a devastated city.

The air, she says, smelled of burnt flesh. Houses were riddled with bullet holes, the furniture inside burned or bashed with sledgehammers. Residents led her to three bombed-out buildings. Fincanci entered one and saw within the basement rubble a jawbone and a pair of eyeglasses. She could immediately tell that the jawbone was a child’s.

Fincanci had not brought her forensic tools. She had assumed that this visit was preliminary, a time to talk with Cizre residents about their medical needs. So, she snapped pictures of the bone, the glasses and the surrounding debris with her cell phone. Residents later confirmed that the building had been home to a young family.

A few days later, Fincanci wrote a report and posted it on the website of the Human Rights Foundation of Turkey, a volunteer organization she helped found in 1990. She also sent the report to Turkey’s internal affairs office. Fincanci wrote that the military had committed atrocities against innocent civilians. She demanded a full investigation. Instead, in June 2016, the government charged her with spreading terrorist propaganda. “I was arrested and sent to prison,” Fincanci says.

Weak regimes

Across the ages, scientists have come under fire for all manner of offense, often tied to the work they do. Chinese astronomers Hi and Ho were executed over 4,000 years ago, according to lore, for failing to predict a solar eclipse. In 1633, the Roman Catholic Church convicted astronomer Galileo Galilei of heresy for stating that the Earth revolves around the sun — a concept antithetical to the church doctrine that put the Earth at the center of the universe. He spent the remaining nine years of his life under house arrest.

In the United States, during the Red Scare of the 1940s and 1950s, government officials monitored and interrogated academics seen as Communist sympathizers. Princeton University physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, a leader of the Manhattan Project, was accused of being a national security risk and lost his security clearance.

Sign up for our newsletter

We summarize the week's scientific breakthroughs every Thursday.

In the aftermath of World War II, on December 10, 1948, the United Nations adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights so that atrocities of the Holocaust would never be replayed. The document stated that every person everywhere has the right to life and liberty, freedom from slavery and torture, the right to work and education, and the freedom of opinion and expression.

The declaration provided a blueprint for how people around the world ought to be treated, yet human rights abuses, against scientists and others, have continued.

The Cold War’s end in 1991 led to a shift from clearly totalitarian regimes where citizens had few personal and political freedoms to countries that appear democratic but exhibit varying levels of authoritarian control, says Andrew Anderson, executive director of Front Line Defenders, a human rights organization based in Dublin.

The blurred line between authoritarianism and democracy in Turkey under President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is a case in point, Anderson says. Scientists almost anywhere can find themselves under fire as even staunch democracies, including Greece and the United States, struggle to balance state interests and academic freedoms. Some scientists are attacked for sharing their research and others stumble into dangerous situations while doing their jobs, such as doctors accused of providing medical care to protesters or rebels. Others feel compelled to use their standing as public figures to resist and expose wrongdoing.

Quantifying the number of scientists whose human rights are under threat is challenging, but a November 19 report from Scholars at Risk, a nonprofit organization that helps persecuted academics, provides some context. From September 1, 2018, to August 31, 2019, the organization documented 324 attacks on students and academics, including scientists, from 56 countries, says Scholars at Risk advocacy director Clare Robinson. The report also points to countries with increasing restrictions on academics, including India, China, Sudan, Brazil and for the fourth year in a row, Turkey, where thousands of academics have been charged with disloyalty, treason and terrorism.

“Thanks to international solidarity and support, they couldn’t hold us for a long time. They had to release us.”

Şebnem Korur Fincanci

Scientists, professional organizations and human rights groups have been mounting international campaigns to help persecuted colleagues. Numerous groups agitated on Fincanci’s behalf, circulating petitions, sending letters and holding demonstrations. But even when advocacy helps free scientists from detention, the accused can find their professional and personal lives upended. Some must live in exile, cut off from their support systems and their work. Others wind up unemployed.

After 10 days in jail, Fincanci and two detained journalists were released to await trial. “Thanks to international solidarity and support, they couldn’t hold us for a long time,” she says. “They had to release us.” The propaganda charges were dropped in July. Fincanci now faces 2.5 years in prison for signing a petition along with more than 1,000 scholars to demand an end to the fighting between Turkish forces and the PKK.

Persecuted for doing a job

In April 2016, disaster medicine researcher Ahmadreza Djalali was in Tehran to help develop a training program for Iranian hospitals on emergency responses to disasters. The invitation, from the University of Tehran and Shiraz University, was not unusual. Djalali, an Iranian-born scientist living in Sweden and affiliated with research centers in Sweden, Belgium and Italy, visited research centers and universities in Iran a few times a year. But this time, officials from the country’s Ministry of Intelligence detained Djalali and placed him in Tehran’s Evin Prison, where political opponents of the Iranian government are often held. In October 2017, under charges that he was a spy for Israel, Djalali was sentenced to death.

“He [is] just a researcher. He is innocent and didn’t do anything against his country.”

Vida Mehrannia, wife of Ahmadreza Djalali

Djalali was targeted for refusing to help with Iran’s espionage efforts, says his wife, Vida Mehrannia. Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence contacted Djalali twice, she says. In 2012, officials asked him to work for Iranian military and intelligence centers, and in 2014, they asked him to cooperate with Iran’s intelligence service to spy on European counterterrorism operations. Djalali, she says, refused both requests.

Mehrannia says Djalali was tortured and placed in solitary confinement in the early part of his detainment. Under duress, he signed multiple false confessions, which were later used in his conviction. His lawyer was forbidden from attending the proceedings, and the judge did not review any of Djalali’s documents.

Mehrannia, who is in Sweden with the couple’s two children, says her husband’s health is failing. He has lost 20 kilograms, and blood tests indicate that he may have leukemia. Numerous organizations and scientists have come out in support of Djalali, including through a 2018 letter signed by 124 Nobel laureates sent to Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

“He [is] just a researcher,” Mehrannia says of her husband. “He is innocent and didn’t do anything against his country.”

While Djalali’s case is extreme, scientists can face peril when their work appears to contradict or impede government efforts. As president of Greece’s independent statistics office, ELSTAT, from 2010 to 2015, economist and statistician Andreas Georgiou confirmed that the country had been underreporting the size of its deficit to avoid economic sanctions by the European Union. In particular, he determined that the 2009 deficit was 15.4 percent of GDP, not 13.6 percent as previously reported.

Although EU officials have repeatedly validated Georgiou’s numbers, in January 2013, he was charged with making false statements about the 2009 government deficit — a felony in Greece that carries a possible life sentence. While he was ultimately cleared of that charge in March 2019, other charges are ongoing. “They’re using statistics as a political weapon,” says Georgiou, now a lecturer in statistical ethics at Amherst College in Massachusetts.

The list goes on. In August, Ricardo Galvão was fired as director of Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research. Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro, who had begun to open more Amazon rainforest to mining and other commercial activities, disagreed with an institute report showing that deforestation from April to June 2019 was almost 25 percent higher than during the same period the year before. And on November 7, the New York Times reported that Russian security forces, masked and carrying automatic weapons, raided the country’s prestigious Lebedev Physical Institute in Moscow and interrogated the director for six hours about a purported plot to export glass with military applications. The institute’s governing council derided the raid, saying in a statement that such actions “are impossible to imagine in a civilized country in which law enforcement agencies concern themselves with real, not invented, problems.”

Medical personnel face risks just by providing medical care to people who are seen as hostile to a governing party. During the ongoing crisis in Syria, the government and its Russian allies have launched 583 attacks on medical facilities, with 912 medical professionals killed, between March 2011 and August 2019, according to the New York City–based advocacy group Physicians for Human Rights. Those numbers do not account for medical staff who sustained injuries but survived or fled the country, says Susannah Sirkin, the organization’s director of policy.

In Sudan last December, when protestors demonstrated against the government of then-President Omar al-Bashir, the military responded with force against both the protestors and those rushing to their aid. Physicians for Human Rights reported in April that it found support for allegations that police and security forces intentionally attacked at least seven Sudanese medical facilities. The group’s independent assessment of postmortem records supports claims that police shot physician Babiker Abdul Hamid in the chest in January as he tried to explain that doctors were simply treating the injured. “He said he was a doctor, and he was shot point blank,” reported one eyewitness. Sudan has claimed that he was shot by “infiltrators.”

How a government treats people who offer medical care can serve as a litmus test for academic freedom, Sirkin says. “It’s never a crime for a doctor to treat a sick person.”

Scrutiny of Chinese scientists

Sharing findings with colleagues around the world is central to science. For years, U.S. funding agencies and research universities have encouraged collaboration between Chinese and U.S. scientists, says Xiaoxing Xi, a physicist at Temple University in Philadelphia. But collaborating has become riskier.

Xi, who earned his doctorate in China before emigrating to the United States in 1989, has traveled frequently to China and worked with partners at Peking University, Tsinghua University and Shanghai Jiaotong University. His research involves fabricating pure materials for studying their intrinsic properties. Those materials eventually could wind up in devices such as cell phones. “I do fundamental research,” Xi says. “I do not do research which is classified or restricted.”

In May 2015, Xi was named chair of Temple’s physics department. Two days later, FBI agents burst into his home, pulling Xi, his wife and two daughters from their bedrooms at gunpoint. Xi describes it as a scene out of a movie.

Xi says FBI agents interrogated him for two hours. The agents thought he had shared sensitive information with China, particularly about a device called a pocket heater. Xi quickly realized that the agents had gotten the science wrong. The information he had shared was not sensitive; it was about a different device, not a pocket heater. But clearing his name took months, by which point his reputation was in tatters.

On the same day that Xi was arrested, the Committee of 100, a nonprofit organization based in New York City that supports Chinese Americans in U.S. society, held a news conference to discuss a similar case. Sherry Chen, a hydrologist at the National Weather Service, had been arrested in October 2014 on espionage charges related to allegedly sharing information about the nation’s dams with China. Her case was dropped one week before trial. In December 2014, charges against two Chinese biologists working at Eli Lilly and Company in Indiana were dismissed.

“So you have … four individuals accused of very serious crimes and yet all have their cases dropped. That’s just very unusual,” says Jeremy Wu, a retired U.S. Census Bureau statistician who is on the Committee of 100 board.

To find out what was going on, Wu contacted Andrew Chongseh Kim, a lawyer at Greenberg Traurig LLP in Houston with some statistics expertise. Kim looked at a random sample of 136 cases involving 187 individuals charged under the Economic Espionage Act between 1997 and 2015. Kim recognized that focusing on that one act would not cover all the cases — Xi was charged under a separate statute, for instance — but it was the most straightforward means of quantifying the problem.

“We have to be sure that everything we say cannot be twisted by the government to charge us.”

Xiaoxing Xi

Charges against people with Chinese names grew from 17 percent of more than 100 defendants from 1997 to 2008, an 11-year span, to 52 percent of the 80 or so who were charged over the next six years, Kim reported December 2018 in Cardozo Law Review. Concerns about economic espionage have been growing in recent years and seem to be centered on Chinese Americans suspected of sharing trade secrets with businesses in China, Kim says.

Some espionage cases against Chinese-American scientists are legitimate. Boeing engineer Dongfan “Greg” Chung was sentenced to 15 years in prison in 2010 for stealing trade secrets for China regarding the U.S. space shuttle program. And Walter Lian-Heen Liew was sentenced to 15 years in 2014 for selling trade secrets to state-owned Chinese companies about a white pigment created by DuPont.

In Xi’s case, the charges were dropped in September 2015, and he returned to work. But his professional career has not recovered. He never did get to serve as chair of his department, his federal grants and contracts have dwindled from nine before his arrest to two today and his lab has shrunk from 15 members to three. Xi says his family remains in a state of perpetual vigilance. “We have to be sure that everything we say cannot be twisted by the government to charge us,” he says.

Rising up in Turkey

While some scientists unwittingly stumble into bad situations, others act as whistle-blowers. A decade ago, hope was mounting that Turkey could emerge as a democratic stronghold in the troubled Middle East. And Erdoğan, who served as prime minister for over a decade before he became president in 2014, appeared moderate. As president, though, Erdoğan has turned toward authoritarianism.

Turkey’s academics have been pushing back. In January 2016, 1,128 Turkish scholars, including Fincanci, signed the Peace Petition. Accusing Erdoğan’s government of the “deliberate massacre and deportation” of civilians, the petitioners demanded an end to the fighting. Turkey responded by suing over 800 signatories and pressuring universities to retaliate against those employees. Almost 500 scholars lost their jobs.

Fincanci was forced to retire from her job at Istanbul University and is appealing the 2.5-year prison sentence she received for signing the document. “I have been banned from public service,” she says.

Food engineer Bülent Şik was already caught up in the country’s criminal justice system when he signed the petition and subsequently lost his job. In 2011, Turkey’s Ministry of Health sought to find out why cancer rates were so high in the country’s northwestern industrial cities. Şik, who served as a team leader for one of the 16 resulting projects, was tasked with looking for contaminants in water and produce in four industrial provinces. His home city of Antalya, where industries are rare, served as a control. Şik ’s team studied 1,440 locations encompassing about 7 million people, including 1.3 million children.

Between 2013 and 2015, the team found that in 52 locations, people’s drinking water was dangerously high in lead, aluminum and arsenic, which have been linked to cancer. Almost a fifth of the food sampled contained pesticides above the legal limit. Şik’s team identified 66 types of pesticide residues, 26 of which are known to disrupt the endocrine systems of infants and children.

The cumulative effect of ingesting those pesticides throughout childhood could be catastrophic, says Şik, speaking through a translator. “I felt that this was my scientific responsibility to explain those results and share [them] with the public.”

In 2015, representatives from all 16 projects and the health ministry pledged to make the findings public. But the Ministry of Health never released the information. So, in April 2018, Şik published a four-part series about his findings in the national newspaper Cumhuriyet. Government officials sued Şik for distributing confidential information. At one of several trials, he defiantly spent an hour and a half describing his findings.

“It is our freedom to say whatever we want during our defense. I used this freedom to explain the rest of the findings,” Şik says. At his latest hearing on September 26, he was sentenced to 15 months in prison, a decision he is appealing.

“I felt that this was my scientific responsibility to explain those results and share [them] with the public.”

Bülent Şik

While the Universal Declaration of Human Rights lays out the fundamental rights of all people, it lacks enforcement teeth. More people need to come to the aid of persecuted scientists, Anderson says. “If we want to secure democracy and human rights, we need to mobilize. We need to support the people that are willing to stick their necks out.”

More than four decades ago, the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine established an advocacy arm for scientists experiencing persecution worldwide. The National Academies’ Committee on Human Rights works behind the scenes to research allegations of persecution against scientists and to advocate on their behalf.

Other organizations have also been lending their support. In 2018, six professional statistical societies commended Georgiou for his work in Greece, noting his “upholding of the highest professional standards in his public service in the pursuit of integrity of statistical systems.” That same year, more than 40 organizations signed a petition calling for Greek officials to halt proceedings against Georgiou.

In October, the American Physical Society awarded Xi a 2020 Andrei Sakharov Prize for his “articulate and steadfast advocacy in support of the U.S. scientific community and open scientific exchange, and especially his efforts to clarify the nature of international scientific collaboration in cases involving allegations of scientific espionage.” And in September, members of 60 scientific societies wrote a letter calling on the U.S. government to find “the appropriate balance between our nation’s security and an open, collaborative scientific environment.”

In Turkey, where most universities are state-run, sustained international pressure has yielded limited success, says Robinson, of Scholars at Risk. “A lot of academics are now being acquitted in Turkey but then they’re being reassigned to [remote] universities or regions where they will be forgotten.”