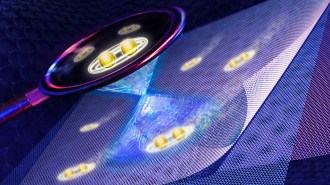

Hula-hooping robots reveal the physics behind keeping rings aloft

Gyrating objects should be hourglass-shaped to hold a hoop steady

Experiments with hula-hooping robots revealed how the hoops stay up, providing some tips for humans aiming to perfect their technique.

Klaus Vedfelt/Getty Images