How a sea anemone grows its tentacles

Creature's cells change shape to form appendages

- More than 2 years ago

Making a sea anemone tentacle takes a bit of stretching, researchers report in the May 15 Development.

Little is known about how the largely sedentary creatures form their multiple appendages. “What I expected to find were stem cells at the base of the tentacle,” says developmental biologist Matthew Gibson of the Stowers Institute for Medical Research in Kansas City, Mo. Those cells, he figured, would then produce other cells to build the protrusions.

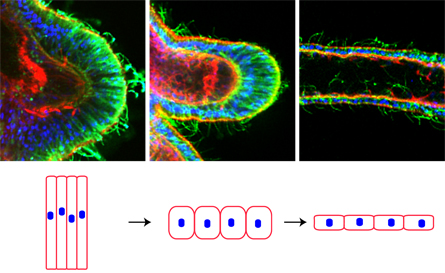

Instead, by examining growing larvae under a microscope, Gibson and his colleagues found that starlet sea anemones (Nematostella vectensis) form tentacles from thick patches of cells called placodes. Rows of tall, thin cells at the edges of these disks gradually flatten and become short and squat, then pancakelike. Flattening the ring of cells causes the interior of the placode to telescope outward — and into a tentacle that the sea anemone will use to catch food passing by.

The researchers don’t yet know whether other animals produce tentacles this way.