How English became science’s lingua franca

History and economics helped the language edge out German, French and Russian

TRANSLATED English has become the international language of science. A historian explains how and why that happened.

trait2lumiere/iStockphoto

- More than 2 years ago

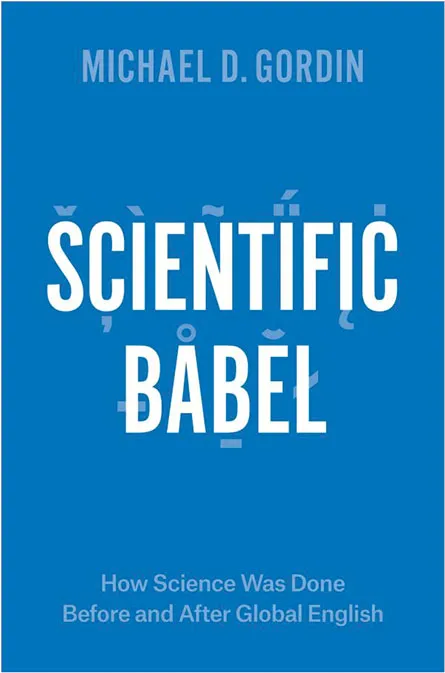

Scientific Babel

Scientific Babel

Michael D. Gordin

Univ. of Chicago, $30

When the Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleyev discovered the “periodic law” that he illustrated with a table of the elements, he published his finding first in Russian and then in a German translation. Shortly thereafter, though, the German chemist Lothar Meyer claimed to be first to perceive the periodicity in the properties of the elements when ordered by atomic weight.

Meyer had seen Mendeleyev’s paper. But in it, “periodicity” had been mistranslated as “phased,” leading Meyer to believe Mendeleyev hadn’t noticed how similar properties recurred periodically. For decades, dispute raged over who deserved credit for the periodic law.

Now, almost 150 years later, it seems like a trivial argument. But it serves as an excellent entrée for Scientific Babel, Princeton historian Michael Gordin’s perceptive account of the historical role of language in science. Today’s language of science is English, much as a few centuries ago it was Latin. But between then and now, various tongues — notably German, French and even Russian — have competed with English for supremacy in the realm of scientific communication.

Language, Gordin contends, shapes not only how science is communicated but also how it is done. Science education, journal publishing, international collaborations and various other aspects of the scientific enterprise are colored by issues intermixing language with war, politics and economics.

All those factors in turn play into the present-day dominance of English. As Gordin notes, no single factor can explain that situation, but American political and economic power certainly played a role comparable to that of America’s scientific prowess. And English’s rise is also partly due to the decline of German science, weakened by World War I and then devastated by Nazi ideology.

After World War II, Russian emerged as an important science language, so much so that massive commercial translation efforts were undertaken to make research published in Russian accessible to American scientists. Scientists who spoke other languages found it more convenient to buy the English translations than to learn Russian itself, demonstrating how economic factors contributed to the English takeover of science everywhere.

Gordin’s scholarly assessment of these matters will not have Hollywood entrepreneurs scrambling for movie rights. But it is insightfully and engagingly written, a masterful mix of intelligence and style. He illuminates an important side of science with academic rigor, but without a trace of academic obfuscation. It’s a very pleasant example of the skillful use of language.

Buy Scientific Babel from Amazon.com. Sales generated through the links to Amazon.com contribute to Society for Science & the Public’s programs.